As Stephen Holden points out in his NYT review, Kevin Macdonald's Marley "is far from hagiography; and while stocked with musical sequences, it is not a concert film. Few if any of his songs are heard all the way through [a fact that bothered me]. Marley is a detailed, finely edited character study whose theme -- Marley's bid to reconcile his divided racial legacy -- defined his music and his life." As Marley becomes more absorbed in Rastafarianism, he takes on an almost cult guru persona. This grandiosity may have played a part in his refusal of treatment for the melanoma that would eventually kill him.

There is a town in north Ontario...

Whereas the 2006 Heart of Gold was a poignant foray into nostalgia, a reunion of old friends playing familiar favorites in an easy, loving ramble, the solo performances that constitute Jonathan Demme’s third concert film with Neil Young, Neil Young Journeys, are at times almost confrontational, as if to say – especially in the first set – we’ve been talking about slaughter, love and war, the rumblin’ in the ground, and still we have to ask: When will I learn how to listen, learn how to give back, learn how to heal? The question is not asked plaintively. It is howled, wailed, implored. The second song is "Ohio," delivered as an incantatory denunciation as we watch the historical footage of the events at Kent State and tributes to the four who died.

The second set is tempered with a few lighter pieces – "My My, Hey Hey (Into the Black)," the then unreleased "Leia," which oscillates between the tinkling of a toy piano sounding much like a calliope and a thunderous antique pipe organ – but the set is only slightly less intense with a magisterial rendition of "After the Gold Rush" on the same organ.

The whole often has an almost operatic quality, while at the same time being a palpable valentine to his audience. Just as we think the concert is over, Young seems to have second thoughts in his dressing room and returns to the stage for an encore of "Walk with Me," which he addresses directly to his fans. He closes by setting the reverberating guitar in front of the speakers. As it sings its feedback across the music hall, he periodically shakes and adjusts it in a musical equivalent of action painting, looks back again over his shoulder to the crowd, and heads back to the road.

The concert is juxtaposed with Young’s road trip in a 1956 Crown Victoria, from his hometown of Omemee, Ontario, 90 miles southeast to Toronto’s Massey Hall. Reminiscing, he says that we may lose people along the way but will always have them with us in memory. “I lost some people I was traveling with, I missed a soul and the old friendship.” (Stephen Holden's NYT review)

I have a problem when 1% celebrities -- musicians, movie stars, athletes -- drop in to show their solidarity with the Occupy movement. The elephant in the crowd leaves me squirming. So as I came to know Rodriguez over the course of an hour and three quarters, my admiration for both the music and the man grew exponentially. Swedish director Malik Bendjelloul's documentary, Searching for Sugar Man, is the story of a poor poet/singer-songwriter who had the good fortune to record two albums in Detroit, and then the misfortune to have them go unheard by his countrymen. It is the story of the South African anti-apartheid movement, an uprising fueled, at least by its white proponents, with bootleg recordings of Rodriguez's music, a development of which the musician was wholly unaware in a pre-Internet era and a South Africa sealed off from the rest of the world. It is the story of an ascetic artist who languished in obscurity, but in 1998, learns of his South African fame, flies there to play to what he does not realize will be packed adoring crowds and will result in a series of South African tours in subsequent years (as well as tours of Sweden and Australia). Sold-out concerts are profitable, and yet, Rodriguez gives the money away, and continues to work as a construction laborer and to live in a tiny, ramshackle house. Not least, it is the story of family devotion and love and the redemptive power of art.

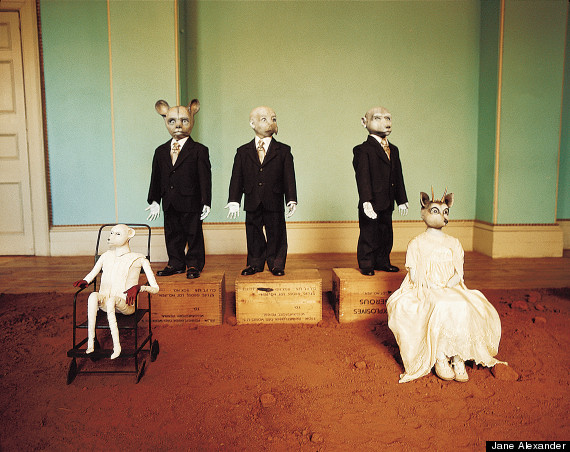

I saw Searching for Sugar Man the weekend before I saw the South African artist Jane Alexander's exhibition Surveys (From the Cape of Good Hope) at the Contemporary Art Museum Houston. It was an astounding synchronicity. Art in America conducted an interview with the artist.

No comments:

Post a Comment