To illustrate the degree to which a critical viewing benefits from context, there could hardly be a better movie than Peter Bogdanovich's 1968 Targets, in which Bogdanovich seamlessly weaves two disparate threads together. The main story involves the murderous impulses our culture of violence provokes. The secondary one relates to the tropes our imaginative literature has employed over time as vicarious catalysts for the dark side of our psyches.

A Culture of Murder

Of Targets' two parallel plots, which will intersect in the finale, the main story is based on 25-year-old Charles Whitman who, on August 1, 1966, in the wee hours, stabbed and shot his mother as she slept, then slew his sleeping wife, burying each, as it were, in a shroud of the covers of her bed.

|

Charles Whitman, UT mechanical

engineering student and former U.S. Marine |

In late morning, Whitman entered the University of Texas, Austin's 307-foot tower, where he bludgeoned a receptionist to death, then opened fire on people in the stairway, killing two before stepping onto the observation deck from which he killed eleven more on the freeway below and wounded 31 in the course of 96 minutes. The University of Texas massacre, as it would come to be known, remained the deadliest campus shooting in the United States until the Virginia Tech shooting in 2007 ... and still counting.

Gun violence is endemic to American culture and took place at schools throughout the 18th, 19th, and first half of the 20th centuries for the same reasons murders took place outside schools then and take place anywhere now. They were and are targeted at specific individuals as retribution for real or perceived wrongs. Jealousy is probably the most common motivating factor, but material envy, employment dismissals, property disputes, theft, those sorts of things, are also cited as righteous justification for acting on moral indignation.

Attempts to alter the political power dynamic of the status quo are another common rationale. In the early history of the colonies, people took the law into their own hands to abuse the British and upset the status quo. Consider the mob that fomented the 1773 Boston Tea Party and Nathaniel Hawthorne's 1831 story "My Kinsman, Major Molineux" of a colonial tar-and-feather attack.

The young nation's embrace of the institution of slavery would mean that from Lincoln on, citizens would do the same in an attempt to preserve the status quo. Unlike the wronged individual who acts alone, murder motivated from a political bias is often undertaken through collective encouragement. Lincoln's assassin, John Wilkes Booth, was part of a wider 1865 conspiracy. In 1951, founder of the NAACP, Harry T. Moore and his wife Harriette, were killed by a bomb that an anonymous Ku Klux Klan cohort placed under their Florida home.

Black voter registration organizer Lamar Smith was shot in cold blood in broad daylight in 1955; the killer was never brought to justice. Less than a decade later, civil rights activist Medgar Evers was killed in June of 1963 before John F. Kennedy's assassination in November; the KKK murdered three civil rights workers – James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner – during the Freedom Summer of 1964; and Malcolm X was assassinated in 1965.

I am not attempting a history of the KKK and the Southern institution of lynching, nor do the incidents cited represent anything like a complete catalog of the casualties of the civil rights movement, but they speak to a dark underbelly that roils within the American experience. For all our talk of democracy and rights and justice and equality, the reality is complex and frequently ugly, and too often a mob mentality has held sway.

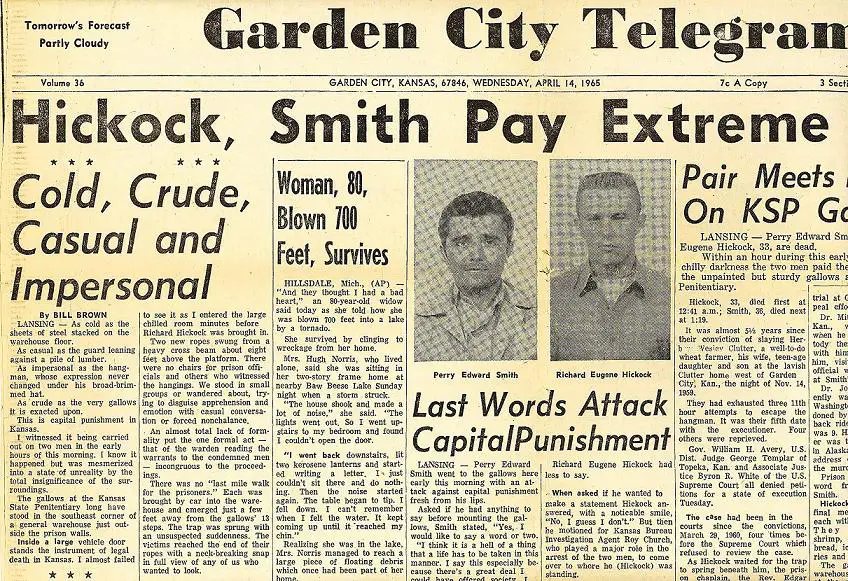

What began to change in the late 1950s, what makes random killing so unlike an individual's wanting to get even or a mob's xenophobia, is the lack of definable motive. What the chilling 1959 Dick Hickcock and Perry Smith murders of the Holcomb, Kansas, Cutter family – popularized by Truman Capote's In Cold Blood, first in 1965 as a four-part serial in The New Yorker, then in book form in 1966 – and Whitman's 1966 Austin shooting spree, what these events ushered in was a new era of indiscriminate rampage murder carried out by individuals with no personal or political agenda that meshes with predominate cultural mores.

The Gothic Tale

A fascination with tales of horror accompanied the social sea-changes of the Industrial Revolution in the latter half of the 18th and in the 19th centuries and was coupled with the concurrent rise of a new – a novel – literary form. The Romantics, captivated by the novel, became especially intrigued with early Gothic tales.

The 20th century, experiencing the paranoia of Joseph McCarthy's House on Un-American Activities Hearings, witnessing the hydrogen bombs' destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, living through the 1950s Cold War threat of nuclear annihilation, turned to the movies' tales of monsters, aliens, and mad scientists – metaphorical embodiments of the bogeymen who engendered a collective panic smoldering just below the surface of normalcy.

Gothic plots are populated by a decaying aristocracy that Bogdanovich echoes in Targets with horror movie icon Boris Karloff's horror movie icon Byron Orlok – for what aristocracy does America most worship but the aristocracy of stardom and celebrity? The crumbling castles they inhabit, with their nooks and crannies, hidden corridors and subterrestrial chambers, are metaphors for the subterranean reaches and precarious nature of the human mind.

While Horace Walpole’s 1763 The Castle of Otranto, the book to which all Gothic novels can be traced; Ann Radcliffe’s 1794 The Mysteries of Udolpho; and Matthew Gregory Lewis’s 1796 The Monk (of which E. T. A. Hoffmann’s 1815 The Devil’s Elixirs is an adaptation) are not doppelgänger stories per se, they are chock full of intended and unintended mistaken identities, and they spoke powerfully to a 19th century fascination with folklore and to superstition and fears stoked by the unknown – much as our fears today are fueled by an Ebola epidemic in West Africa, ISIS threats from the Arab world, and widening economic divisions at home.

|

| The Monk |

In 1818 Mary Shelley imagines Frankenstein, the mad scientist who, daring to play God, wreaks havoc on his world with his creation. Though movie titles don't reflect it, Shelley’s novel is titled Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, a reference to the Titan god whose hubris made him think he could steal fire from Zeus to better the human condition. Icarus, too, brought destruction on himself by flying too close to the sun. Prometheus, Icarus, and of course the Faust of German legend are the prototypes for the mad scientists who populate our popular literature and film.

Irishman Bram Stoker spent a number of years delving into European folklore, especially tales from the Carpathian Mountain regions of Hungary and Romania, before introducing the elegant, eloquent Count Dracula in his 1897 Gothic horror novel. Dracula was met with critical acclaim, though it was not until F. W. Murnau’s silent Nosferatu appeared in 1922 that the story became cloaked in its iconic status.

Portrayed by Max Schreck, the vampire in Murnau's version is called Count Orlok after whom Bogdanovich will name his horror movie star Byron Orlok. Bogdanovich's Orlok's Christian name, "Byron," of course, alludes to the English Romantic poet Lord Byron and also has a ring about it of "Baron" as "Orlok" does of "Eric," the two parts of the doppelgängers Baron/Eric whom Karloff portrays in Roger Corman's 1963

The Terror.

|

| Max Schreck in F. W. Murnau's 1922 NosferatuCinematography: F. A. Wagner (and Gunther Krampf, uncredited) |

Schreck’s vampire is a chilling character, a demonic gargoyle with almost none of its humanity intact. By contrast, Bela Lugosi’s Count Dracula, for Tod Browning’s 1931 adaptation based on the 1924 stage play by Hamilton Deane and John L. Balderston, is a cultured, cultivated, erudite, urbane sophisticate and hospitable host who is simultaneously furtive, inscrutable, enigmatic. Lugosi’s is the quintessential Dracula, the Dracula against whom all subsequent Draculas will be judged.

|

Bela Lugosi in Tod Browning's 1931 Dracula

Cinematography: Karl Freund |

Targets and The Terror

Though the writing and production photography had been completed by late 1967, Targets was not released until August of 1968 – after the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. in April and Robert Kennedy the following May. Bobby Thompson (played by Tim O'Kelly) is the psychotic killer standing in for Austin sniper Charles Whitman, whose story is told in parallel to Byron Orlok's played by the iconic Karloff, who would live less than six months after the film's release. Orlok's world of horror movies has passed. He believes he has become nothing more than a curiosity destined for the dustbin of history, though his fans, old and young alike, eagerly await his arrival.

Bogdanovich came up with the parallel story idea, in collaboration with his then-wife Polly Platt who went on to become a writer and production designer in her own right, because Roger Corman, one of the great B-movie producers and directors of American cinema who mentored any number of important directors, had found himself with a contract situation in which Karloff owed him two days' work. Corman asked Bogdanovich, his directorial assistant at the time, if Bogdanovich could come up with an idea to use Karloff interspersed with 20 minutes of old footage – a 1963 Karloff vehicle called The Terror – and 40 minutes of new footage, so that Karloff could fulfill his two-day contract obligation without exceeding it. Corman also insisted that Bogdanovich keep the budget under $125,000.

Apparently, Targets was not the first time the result of Corman's down and dirty work ethic had left Karloff with additional contract days to reconcile: "Realising that he was going to finish The Raven [in 1963] ahead of schedule," David Parkinson reports, "Corman contacted Leo Gordon (the hulkingly prolific character actor who had scripted such early Cormans as The Wasp Woman, [in] 1959) and offered him $1,600 to whip up a Gothic scenario that could exploit Daniel Haller's atmospheric sets. Corman was also aware that Boris Karloff would still have two days left on his contract and asked if he would be willing to shoot scenes that could be used in the provisionally titled The Lady of the Shadows," which became The Terror.

In the documentary A Decade Under the Influence, Platt says that in discussing narrative possibilities with Bogdanovich, she began to wonder, "Why aren't those Boris Karloff movies scary? I decided what was modern horror was someone shooting at you for no reason." The concept they developed was to take Whitman's story and link it with a horror movie star who is retiring because he feels his kind of horror is passé. As is often true of constraints, the challenges led to a highly creative meditation on the narrative violence of the horror genre presciently juxtaposed against an emerging violent reality that, as we now know, would tragically become the norm.

Ultimately Bogdanovich used so little of The Terror that it begs for a viewing on its own in conjunction with Targets. The Terror is generally considered inferior to Corman's celebrated Poe cycle – House of Usher, The Pit and the Pendulum, The Raven – for all of which he used the cinematographer Floyd Crosby who is uncredited on The Terror.

In classic Gothic fashion, The Terror employs the mistaken identity/doppelgänger trope. Napoleonic légionnaire Lieutenant Andre Duvalier (Jack Nicholson, who had worked with Corman in Little Shop of Horrors and The Raven) has become detached from his regiment and is roaming the Baltic coast when he comes upon Helene (played by Nicholson's first wife Sandra Knight). Duvalier follows Helene to the cottage of a peasant sorceress, Katrina. Helene disappears, and seeking to find her, Duvalier makes his way to the castle of Baron Von Leppe, a recluse haunted by the ghost of his bride, Ilsa, whom he murdered when he found her with a lover 20 years before and to whom Helene bears an eerie resemblance.

|

| The castle of Baron Von Leppe on the Baltic coast |

Ilsa's ghost, under Katrina's spell, is made to torment the Baron, who admits to Duvalier that he killed Ilsa but says it was his valet, Stefan, who killed her lover, Eric. The Baron claims the ghost of Ilsa has come to relieve him of his guilt, but instead, Ilsa finally commands that he kill himself. The Baron believes suicide will condemn him to eternal damnation, but Ilsa insists it is the only way they can be reunited. At the moment the witch, Katrina, is revealed as Eric's mother seeking vengeance for her son, the Baron's valet reveals that, in actuality, he, Stefan, killed the Baron, and it is

Eric who has taken up the Baron's identity and residence in the castle. Mortified, Katrina rushes to stop Eric from suicide but is struck by lightning and suffers a fiery death.

Targets opens with the final sequence of The Terror: a falcon plunges at us and violent waves explode against a craggy coast above which the dark castle looms. Inside the shadowed halls, as Eric starts to raise the gate to the mausoleum, Stefan rushes to stop him, but Eric shoves him to the floor. Outside, Duvalier tries to break into the crypt from the chapel, while inside, down below, the ghost of Ilsa watches as Eric opens the coffin where Ilsa's corpse, to his horror, lies.

Eric swings 'round to open the floodgates of destruction as Ilsa sets upon him. Stefan bounds down the staircase and dives into the watery conflagration to pull her incarnation from Eric. Then Duvalier descends just in time to drag Helene/Ilsa from the engulfing waters and carry her out of the edifice, the metaphor for Eric/Baron's psyche. Bogdanovich cuts to

The End without our seeing the

denouement in which Duvalier reaches the tangled grounds, lays her body down, and she withers into putrefaction as the house collapses into ruin.

|

| Jack Nicholson and Sandra Knight in Roger Corman's 1963 The TerrorCinematography: John Nicholaus (and Floyd Crosby, uncredited) |

So begins

Targets with The End... and

cut...

...to Byron Orlok in a studio watching The Terror and looking none too happy about it. Present are Corman-esque producer Marshall Smith and publicist Ed Loughlin, along with writer/director Sammy Michaels played by Bogdanovich and named for Bogdanovich’s mentor and uncredited Targets script doctor, Sam Michael Fuller. Sammy has written a new script in which they all expect Orlok to star, but Orlok preempts the pitch when he says out of the blue, "I'm not making any more films, Marshall. I'm retired." Following a dressing down from Marshall, as Orlok's driver holds the door for him, Sammy makes another appeal. "There's nobody else for it. The part is you." Orlok's mind is made up: "I'm an antique, out of date."

In The Terror, when Duvalier first arrives at Von Leppe’s castle, the Baron shows him through the rooms. In Targets, the first time we find Bobby Thompson in his parents' suburban house where he lives with his wife, likewise he slowly and deliberately surveys each room and the objects in it: guns, hunting gear, family photos.

The Baron wanders through the rooms and reflects, "What you see, Lieutenant, are the remains of a noble house. Relics. Ghosts of past glories." Duvalier protests, "A noble heritage is something to be proud of, Baron." Like Duvalier, Sammy refuses to dispense with the staying power of Orlok's past glories. "What do you mean?" Sammy asks when Orlok says, "I'm an anachronism." "Sammy, look around you. The world belongs to the young. Make way for them. Let them have it." And cut to...

Orlok's head in the crosshairs. Cut...to extreme close-up of Bobby Thompson's eye at the gun site. Cut...to extreme close-up of Bobby's index finger on the trigger. Cut...to Bobby aiming the rifle in the gun shop. And... click. That sound, that clean click, functions as the fifth cut – or shot if you will – of Bobby's establishing sequence. Then Bobby's first line: "I'll take it," he says and grins broadly. The gun owner spots Orlok across the street, he and Bobby conclude their business, and our final cut of the sequence is to the trunk of Bobby's car, a veritable arsenal of weaponry and ammunition.

That quick sequence tells us exactly where the plot is headed, so how we get there is what's important. His film-making techniques, Bogdanovich has said, were drawn from years of interviews with great auteur directors. Alfred Hichcock had told him, "Never use establishing shots to establish. Only use them when you want dramatic effect," which is precisely how Bogdanovich establishes his pair of opening scenes. Howard Hawks had told him, "Always cut on movement. Then the audience won't see the cut," which is exactly the technique László Kovács as cinematographer and Bogdanovich as editor use for the highway sniper scene and the final drive-in massacre.

Bogdanovich also plants references to the climax throughout the script. Orlok and his assistant have gone out for drinks to celebrate his freedom, when Ed Loughlin arrives to go over arrangements for the next night's personal appearance. "I'm not making that appearance, Ed," says Orlok. Loughlin tries to negotiate, "This has nothing to do with any difference between you [and Marshall]. It's innocent people affected here."

|

| Howard Hawks's 1931 The Criminal CodeCinematography: James How and Teddy Tetzlaff |

Of

Targets many ambitions, one is its obvious homage to the movies and Bogdanovich's cinema mentors. When Sammy drops by Orlok's room at the Beverly Hills Hotel that night to try once more to convince Orlok to take the role in Sammy's next film, Orlok is watching Howard Hawks's 1931

The Criminal Code on TV, which features Karloff's first significant screen performance. Sammy gets sucked into the movie and keeps shushing Orlok. As the credits roll, Sammy remarks, "All the good movies have been made," echoing Gloria Swanson as Norma Desmond in Billy Wilder's 1950

Sunset Boulevard.

|

"I am big. It's the pictures that got small."

Gloria Swanson as Norma Desmond in Billy Wilder's Sunset Boulevard

Cinematography: John F. Seitz |

"Everybody's dead. I feel like a dinosaur, old fashioned, outdated" Orlok muses, arguing, "I couldn't even play a straight part decently anymore. I've been doing the other thing too long. And even that isn't the point. You know what they call my films today?" he asks Sammy. "Camp. High camp. My horror isn't horror anymore." "Not after this picture they wouldn't," Sammy protests, at which point we can confidently assume that "this picture" is Targets. Orlok rummages through newspapers and tosses one into Sammy's lap. "There. Look at that." The front page headline reads "Youth Kills Six in Supermarket."

The Baron/Eric doubling of The Terror is redoubled in Targets with Karloff playing Orlok playing the double Baron/Eric at the beginning and amplified further still in the final scene as Bobby is rattled, caught between the Orlok marching toward him from the drive-in lot and the larger than life Orlok coming at him from the screen.

More important, a thematic doubling takes place in Targets. Gothic horror is doubled with the real-life Charles Whitman stand-in Bobby Thompson, the old horror and the new – the former fiction, the latter all too real and more akin to sociopath Wild West outlaws like Jesse James, Billy the Kid, Butch Cassidy, and Bonnie and Clyde, whose ostensible enemies were corrupt lawmen and banks but who were really indiscriminate cold-blooded killers, despite their veneration in the American mythos.

Bogdanovich's cinematographer for Targets, the Hungarian-born Kovács, would work with Bogdanovich again on What's Up, Doc?, Paper Moon, At Long Last Love, Nickelodeon, and Mask. There are many marvelous cinematic moments in Targets born of the collaboration between them. One occurs when the camera pans in a slow long shot across Orlok's hotel room from the bar to the dinner tray; the film then cuts to the empty Thomas family living room, mirroring the exact same trajectory across the room. The long takes, which are difficult and of which there are many, are exquisite throughout Targets, and both sniper scenes are sheer genius.

I can't do a better job of describing the camera work of the drive-in sequence than Singer does in The Dissolve, so I will quote at length:

[It] includes one of Bogdanovich’s greatest and most disturbing touches. Pursued by police, Bobby hides out at the drive-in. [We see children on] the playground, [as] Bobby makes his way behind the enormous screen, climbs to the top, and takes aim at the movie goers. [Kovács’s] camera ... doesn’t simply mimic the perspective of the sniper; it mimics the perspective of his bullets as well. As Bobby fires, the lens zooms toward Bobby’s victims at high speed, following the path of the ammunition as it makes its way to its targets. Many films have used point-of-view editing to make the audience feel like accomplices in a crime, and to call into question the audience’s own motives for wanting to watch grisly violence. Few have used point-of-view editing to make the audience feel like the actual murder weapon, or to implicate the viewer so directly in brutality they’ve willingly chosen to witness.

As Bobby fires on the oblivious victims at the drive-in (the portable speakers in each car drown out the gunfire), Orlok realizes what’s happening and heads toward the screen. Confused by the sight of the actor approaching while his projected image looms overhead, Bobby freezes, giving Orlok just enough time to disarm him. New Hollywood might be more frightening, [Singer concludes,] but at least on this day, Old Hollywood still reigns supreme.

I do not think one could weave these two stories together with such economy in any medium other than cinema. Maybe someone could do it in prose, but I really doubt the piece would come off as seamlessly as Bogdanovich and Kovács make it on film – BANG, BANG, BANG, BANG. The camera

shots become the gun's reports. The whole pace of editing embodies the title, as

Targets oscillates between eerie calm and gun fire, each shot prefaced with Bobby's audible intake of a single breath.

Two years after

Targets appeared, Haskell Wexler's meditation on journalists' failure to ask ethical questions about whether they record disaster because they are reporting events or because they are pandering to the public's insatiable appetite for tragedy and carnage* opened in 1970.

Medium Cool is the story of a local Chicago television news cameraman who takes under his wing a woman and her young son totally out of their element in the city.

Wexler planned the closing scenes to take place in the urban neighborhood around the International Amphitheatre in Chicago where the Democratic National Convention was being held. The film's style was to be cinema vérité, but when cast and crew found themselves engulfed in the midst a crowd of approximately 10,000 anti-war protesters with 23,000 police and National Guardsmen rolling in on them, the verisimilitude ceased to be a stylistic choice. Wexler shouted to his camera crew to keep the cameras rolling, which they did, as protesters chanted, "The whole world is watching," and the police riot erupted.

Medium Cool closes with a cameraman (Wexler) on a scaffold filming the final scene (which I will not spoil) with a camera mounted on a tripod. The shot starts with camera and cameraman in profile, but the cameraman slowly turns the camera 90 degrees to face us, and then a dolly shot gradually brings us closer until the cameraman disappears, and we sink into the lens as the credits begin to roll. Like Bogdanovich, Wexler makes us complicit in projected spectacles of violence with our appetite for the suffering of our fellows.

|

| Haskell Wexler's 1970 Medium Cool |

Violence, violation are central to our narrative, not only in the myth of the Wild West that glorifies outlaws, but to the historical record of our institutions. Both church and state waged genocide against American Indians for two and a half centuries, while government forces like the National Guard, the Army, and the Coal and Iron Police, as well as private security agencies like the Pinkertons and the Corporations Auxiliary Company have waged armed war against workers and labor unions for 150 years and counting. The Ohio National Guard charged Kent State on May 4, 1970, killing four and wounding nine more, only some of whom were there to protest President Nixon's expansion of the Vietnam War with the Cambodian Campaign.

Recently, police have used what are called maximum non-lethal or less-lethal tactics such as tear gas, Tasers, pepper spray, and rubber bullets against the Occupy movement. Militarized police swept over Ferguson, Missouri, a few short months ago.

Ours is a culture of violence, once metaphorically explored and vicariously experienced in the Gothic mythologies of penny dreadfuls in the 19th century and of American horror movies of the '30s, '40s, '50s, and early '60s. The mad scientist whose monster runs amok, the seductive vampire, the menacing alien who threatens to invade – all were brought vividly to life first in the shadows and fog of black and white and then in the lurid hues of Technicolor.

Bogdanovich limns both the threat and the lure of violence as it emerges in suburban life and then takes up tenacious residence. The disaffected young man no longer simply resents a hypocritical society for its phoniness; he is no longer merely a rebel without a cause.

|

James Dean as Jim Stark in

Nicholas Ray's 1955 Rebel Without a CauseCinematography: Ernest Haller |

The new angry young man seeks to make himself a martyr, but a martyr to what, for a martyr to destruction, to nihilism, makes no sense. He can join an army perpetually at war, and indeed in Bobby's story's second sequence, as he moves from room to room in his suburban environs, is a detail one might easily overlook.

The camera pans past a photograph of Bobby in uniform: he has been in Vietnam. Our young man can come home from war outwardly normal yet inwardly skewed. He need not even have experienced the trigger of combat. He can grow up so saturated in a culture of violence that he believes any hurt or trouble should be avenged by catastrophe. He can walk into a school, a shopping mall, a courthouse – or in a cruel irony, into a movie theater and, in front of the projected image, open fire. He has devolved into a psycho with unconditional access to an arsenal of automatic weaponry.

The Gothic scientist was sometimes mad, but he was typically ethically motivated, an explorer questing after truth and life. Once his experiments were realized, though, he came too late to realize he had created a monster. Our real-life scientists straddle the line between creation and destruction, between inventions that enhance our lives, that promise "progress" and those self-same inventions that threaten life: the dichotomies of the internal combustion engine and global warming, nuclear power plants and nuclear annihilation, fracking technologies and poisoned aquifers, antibiotics and antibiotic resistant bacteria, farm fertilizers and obesity induced diabetes – the list goes on...

_02.jpg) |

| Colin Clive as the mad scientist in James Whale's 1931 FrankensteinCinematography: Arthur Edeson and Paul Ivano, both uncredited |

In Targets, the plan for the revival screening of The Terror calls for DJ celebrity Kip Larkin to interview Orlok. Orlok has relented, having decided he might as well make the personal appearance, so up in Orlok's hotel room, at 3:00 p.m.** before the evening's revival premier, Larkin runs through sample questions: "How do you like being in motion pictures? Is Byron Orlok your real name? What is your next flick gonna be?" Orlok cannot contain his annoyance. "Sammy, this isn't very interesting." ... "This is dull, deadly dull. If this is going to be my last appearance, you might want to do something." Sammy proposes, "Why don't you tell them a story? You know a few scary stories."

What transpires is a remarkable scene. Orlok begins, but stops midsentence to tell Sammy, the director, how to direct: "Put a pin spot on my face." The camera pulls back, and Orlok unspools a story, a scary story, about an appointment with Death personified and an attempt to cheat the Grim Reaper. The camera slowly dollies closer and closer.*** Karloff's delivery is mesmerizing, and the camera's closing in on him makes the other characters drop away, until Karloff alone, the storyteller, is intimately with us.

Since Target's release in 1968, we have seen meaningless slaughter and nihilism spread as an ideology within American culture with repeated government shutdowns and ever-widening economic disparity, and without on the global stage with the spread of third world dictatorships, sectarian civil war, and terrorism. A commitment to shared values and the common weal seems to diminish with each passing year.

In

Target's final scene, Orlok stares aghast at a cowering Bobby, and asks, "Is that what I was afraid of?" Like Robert Oppenheimer witnessing the Trinity nuclear test on July 16, 1945, I am put in mind, as Oppenheimer opined, "of the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita; Vishnu is trying to persuade the Prince that he should do his duty and, to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says, 'Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.' "

|

| July 16, 1945, 5:30 a.m. at the Trinity Site in New Mexico |

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Notes

*Three current movies grapple in different ways with similar questions.

Kill the Messenger follows in the tradition of the based-on-a true-story

All the President's Men and the onus of responsibility journalists must shoulder if they are to function in a democratic society as the Fourth Estate.

Gone Girl holds a mirror to sensational "news" programming that presents conjecture as fact, which the public is all too eager to accept as gospel, no matter how unreasoned and speculative. Finally,

Nightcrawler takes us into the lurid world of local TV news casting ever on the prowl for the most prurient stories to feed our basest instincts. As citizens, in the instance of

Kill the Messenger and

All the President's Men, we are complicit in that we would rather remain blinkered by the comfortable biases of our opinions than face difficult truths that require complicated solutions and sacrifice. In

Gone Girl and

Nightcrawler we are complicit in our insatiable lust for yellow journalism. One of its hallmarks of genius is that

Medium Cool bridges both predilections.

**Throughout the film,

Targets is punctuated with clocks and reminders of the time of day like Bobby's note:

TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN:

IT IS NOW 11:40 A.M. MY WIFE

IS STILL ASLEEP, BUT WHEN SHE

WAKES UP I AM GOING TO KILL

HER. THEN I AM GOING TO KILL

MY MOTHER.

I KNOW THEY WILL GET ME, BUT

THERE WILL BE MORE KILLING

BEFORE I DIE.

(

Before I Die was the working title for

Targets.)

Taken together, the time references serve to reinforce the Dramatic Unities along which the film is organized. The Greek philosopher, Aristotle, instructed that every tragedy, properly constructed, should be limited to the action of a single day – the unity of time; should occur in a single geographic location – the unity of space; and should tell a single story without subplots – the unity of action. Bogdanovich respects Aristotle's paradigm:

Targets takes place over 24 hours; though the characters move through the city, they never depart from LA; and despite the seemingly dual nature of the parallel stories, there is ultimately but one plot – the old horror pales beside the new.

***The take was to be done in a single continuous long shot that required the table at which Orlok and Sammy are sitting be skewed slightly

as the camera encroaches to keep the perspective realistic in the screen frame. Bogdanovich had asked Karloff if he wanted cue cards for the story. "Idiot cards?" Karloff asked, and then, as was his customary way of referring to his lines, "No, no, no" he said, "I have the lyrics."

Bibliography

A Decade Under the Influence. Dir. Ted Demme and Richard LaGravenese. IFC Films, 2003. Film.

Colloff, Pamela. "

96 Minutes." Texas Monthly, August 2006.

Ebert, Roger. "

Targets." robertebert.com 15 August 1968.

Miller, John M. "

Targets." tcm.com, n.d.

Russell, Lawrence. "

Targets." culturecourt.com July 2003.

_02.jpg)