DOPPELGÄNGERS and VAMPIRES: PART I ~~ THE DOPPELGÄNGER

Enemy

The Face of Love

Her

Transcendence

Under the Skin

Locke

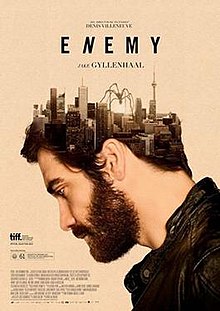

I had been mulling over the rash of doppelgänger stories popping up in multiplexes for months, when I ran across “What’s Up with All the Movies About Doppelgängers?” that Alissa Wilkinson wrote for The Atlantic. The article, which has been oft quoted, cites Denis Villeneuve’s Enemy adapted from Jose Saramago's novel The Double; Richard Ayoade’s The Double based on Dostoevsky's novella; and Ari Posin’s The Face of Love (a list that overlooks several variations on the theme).

Wilkinson thinks the current wave “may reflect the Internet-age anxiety over curating cooler online versions of ourselves.”

I had been mulling over the rash of doppelgänger stories popping up in multiplexes for months, when I ran across “What’s Up with All the Movies About Doppelgängers?” that Alissa Wilkinson wrote for The Atlantic. The article, which has been oft quoted, cites Denis Villeneuve’s Enemy adapted from Jose Saramago's novel The Double; Richard Ayoade’s The Double based on Dostoevsky's novella; and Ari Posin’s The Face of Love (a list that overlooks several variations on the theme).

Wilkinson thinks the current wave “may reflect the Internet-age anxiety over curating cooler online versions of ourselves.”

I reject the hipness of that idea, argue the trend goes much deeper, and suggest that other recent films – Her, Transcendence, Under the Skin, Locke – are variations on the doppelgänger that speak to our fears (but also our hopes) about technology generally, our declining social and economic well-being, and an overall crisis of identity in a society that, social media notwithstanding, increasingly isolates and dehumanizes the individual.

One approach to coming to terms with a world out of balance is to psychologize it, which is essentially what mythology and religion have been doing since time immemorial.

One approach to coming to terms with a world out of balance is to psychologize it, which is essentially what mythology and religion have been doing since time immemorial.

Genesis, one of our Judaic-Christian origin myths, provides an explanation for our dual nature with the story of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. The earliest surviving Old English vernacular literary work, variously dated anywhere between the 8th and early 11th centuries, Beowolf is a story in which the monster can be interpreted as an evil version of the hero.

German “doppelgänger” translates literally as “double goer.” A doppelgänger is not simply a reflection, like Narcissus’s, but an incarnation – either imagined or embodied – of a character’s double.

German “doppelgänger” translates literally as “double goer.” A doppelgänger is not simply a reflection, like Narcissus’s, but an incarnation – either imagined or embodied – of a character’s double.

The earliest manifestations of the idea of the double were the Greek eidolon – an apparition, spirit-image, shade, or phantom of a person, living or dead – and a belief in bilocation wherein an individual is simultaneously located in two places. Shamanism, Eastern religions, occultism, Christian mysticism, all held a belief in bilocation to explain visionary experience.

These antecedents differ from the modern doppelgänger in that the eidolon and the bilocated apparition are typically understood as distinct phenomena apart from the visionary who sees them. Nor do they necessarily imply an evil opposite.

The benevolent and malevolent evil twins of the Zoroastrian Manichean world-view come closer to representing our modern schizophrenic doppelgänger. Though distinct entities, opposite twins provide an obvious metaphor for the two sides of human nature.

The modern doppelgänger is a phenomenon of the protagonist's psyche when faced with a potentially devastating breaking point, a self-protective creation of the protagonist's mind at a time of acute psychological crisis.

The doppelgänger is an extreme of an experience so universal that we have a turn of phrase to describe the sensation of heightened emotional turbulence: "I was beside myself with joy." "I was beside myself with grief."

The Modern Doppelgänger

With many literary precedents, a new – novel – literary form began to emerge in the 18th century. With the dawn of the 19th century, as the Enlightenment waned, the doppelgänger came into its own. The Romantics, captivated by the novel, became especially intrigued with early Gothic tales.

Populated by a decaying aristocracy, these overwrought plots are entangled with male sexual dominance and female repression. The crumbling castles their characters inhabit, with their nooks and crannies and hidden corridors, are metaphors for the subterranean reaches of the human mind.

While Horace Walpole’s 1763 The Castle of Ontranto, the book to which all Gothic novels can be traced; Ann Radcliffe’s 1794 The Mysteries of Udolpho; and Matthew Gregory Lewis’s 1796 The Monk are not doppelgänger stories per se, they are chock full of intended and unintended mistaken identities, and they spoke powerfully to a 19th century fascination with folklore and superstition. (E. T. A. Hoffmann’s 1815 The Devil’s Elixirs is an adaptation Lewis’s The Monk.)

Further, whether she knew it or not, the 19th century reader’s morbid curiosity about the mysteries of personality and the underbelly of the human condition was greatly influenced by philosophical and scientific questions that were by that time swirling amongst the intelligentsia.

Investigations into the mind-body problem have persisted since Plato and were establishing the foundations of psychoanalysis that would come to influence Sigmund Freud. German psychologist and philosopher Franz Brentano, French psychotherapist and philosopher Pierre Janet, and Georg Groddeck would all have a profound effect on Freud's thinking.

Brentano, best known for retrieving the concept of intentionality from Medieval Scholasticism, posited the idea that Wahrnehmung ist Falschnehmung – perception is misception. Janet put forward the concept of traumatic memory, arguing that people’s past experiences affect their reactions to present day trauma. Janet coined the term “dissociation,” one of the hallmarks of the modern doppelgänger. Groddeck (whose mother was a teacher to Nietzsche) was a German writer and physician who laid the foundations for contemporary behavioral studies using what he called psychosomatic medicine.

In The Ego and the Id, Freud says Groddeck insists that “what we call our ego behaves essentially passively in life, and that, as [Groddeck] expresses it, we are ‘lived’ by unknown and uncontrollable forces.” By this Groddeck meant breathing, digestion, circulation, etc., but one can see how this idea could be mistakenly interpreted and refashioned to fit the doppelgänger.

Since the 19th century, the split personality has characterized literary depictions of the doppelgänger. A person, for whatever reason, has been made psychologically vulnerable, causing a crisis in identity.

ENEMY

At one of Caster’s talks a member of a Luddite terrorist group shouts from the crowd, “You are trying to create a God!” When the terrorists mortally poison him with radiation, Caster decides to carry his experiment to its ultimate end by uploading his consciousness into his invention.

The movies are full of doppelgängers. Hitchcock and Polanski revisited the genre often, but perhaps no one has been as obsessed as Brian De Palma. Here are links to MUBI movie lists of Doppelgängers and Doppelgängers, Twins and Look-Alikes, but one film that for some reason never makes it onto the lists is Alan Rudolph’s Secret Lives of Dentists adapted from Jane Smiley's novella “The Age of Grief.”

While Horace Walpole’s 1763 The Castle of Ontranto, the book to which all Gothic novels can be traced; Ann Radcliffe’s 1794 The Mysteries of Udolpho; and Matthew Gregory Lewis’s 1796 The Monk are not doppelgänger stories per se, they are chock full of intended and unintended mistaken identities, and they spoke powerfully to a 19th century fascination with folklore and superstition. (E. T. A. Hoffmann’s 1815 The Devil’s Elixirs is an adaptation Lewis’s The Monk.)

Further, whether she knew it or not, the 19th century reader’s morbid curiosity about the mysteries of personality and the underbelly of the human condition was greatly influenced by philosophical and scientific questions that were by that time swirling amongst the intelligentsia.

Investigations into the mind-body problem have persisted since Plato and were establishing the foundations of psychoanalysis that would come to influence Sigmund Freud. German psychologist and philosopher Franz Brentano, French psychotherapist and philosopher Pierre Janet, and Georg Groddeck would all have a profound effect on Freud's thinking.

Brentano, best known for retrieving the concept of intentionality from Medieval Scholasticism, posited the idea that Wahrnehmung ist Falschnehmung – perception is misception. Janet put forward the concept of traumatic memory, arguing that people’s past experiences affect their reactions to present day trauma. Janet coined the term “dissociation,” one of the hallmarks of the modern doppelgänger. Groddeck (whose mother was a teacher to Nietzsche) was a German writer and physician who laid the foundations for contemporary behavioral studies using what he called psychosomatic medicine.

In The Ego and the Id, Freud says Groddeck insists that “what we call our ego behaves essentially passively in life, and that, as [Groddeck] expresses it, we are ‘lived’ by unknown and uncontrollable forces.” By this Groddeck meant breathing, digestion, circulation, etc., but one can see how this idea could be mistakenly interpreted and refashioned to fit the doppelgänger.

Since the 19th century, the split personality has characterized literary depictions of the doppelgänger. A person, for whatever reason, has been made psychologically vulnerable, causing a crisis in identity.

In 1818 Mary Shelley imagines Frankenstein, the story of a doctor who, in Nick Dear’s contemporary dramatic retelling, is an ambivalent groom on the eve of his wedding. Dr. Frankenstein is the mad scientist who, daring to play God, wreaks havoc on the world with his creation.

Though movie titles don't reflect it, Shelley’s novel is Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, a reference to the Titan god whose hubris made him think he could steal fire from Zeus in order to better the human condition. Icarus, too, brought destruction on himself for flying too close to the sun. Prometheus, Icarus, and of course the Faust of German legend are the prototypes for mad scientists from the 19th century on.

The modern interpretation depicts an individual whose psychic breakdown causes his doppelgänger to emerge. Sometimes, as in Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Sharer, the double serves a therapeutic function, allowing the protagonist to overcome his insecurities and grow, but sometimes the protagonist succumbs to his demons and the doppelgänger leads him into madness.

ENEMY

The ambiguity with which Denis Villeneuve’s Enemy ends leaves us up in the air as to whether Professor Adam Bell is going to come out on the other side or fall victim to his demons.

Adam ostensibly has a girlfriend, though the relationship appears superficial and ambivalent. Oddly, it is the motorcycle-riding double Anthony who is married with a pregnant wife.

I see Adam/Anthony and the two women as crossed: X. The way I read it, the pregnancy is Adam/Anthony’s trigger. When Adam shows up at Anthony’s agent’s offices, the receptionist asks why Anthony hasn't been in for six months. When Anthony’s wife confronts Adam, she tells him she is six months pregnant. Ergo….

The film is framed – and punctuated – by a members-only erotic club where men watch women perform with tarantulas. Most critics draw the link between this motif and Stanley Kubrick's Eyes Wide Shut, but there is also a parallel with David Fincher's Fight Club, the contrast being that Villeneuve's and Kubrick's spectacles involve passive watching, while Fincher's involves active participation. All three make the point of sexual duality and the delicate balance between dominance and repression that can be so easily toppled.

The theme of sexual hegemony is intertwined with and juxtaposed against the equally powerful theme of capitalist hegemony.

The film is framed – and punctuated – by a members-only erotic club where men watch women perform with tarantulas. Most critics draw the link between this motif and Stanley Kubrick's Eyes Wide Shut, but there is also a parallel with David Fincher's Fight Club, the contrast being that Villeneuve's and Kubrick's spectacles involve passive watching, while Fincher's involves active participation. All three make the point of sexual duality and the delicate balance between dominance and repression that can be so easily toppled.

The theme of sexual hegemony is intertwined with and juxtaposed against the equally powerful theme of capitalist hegemony.

An industrialized, corporatized, high tech world has put us at a serious remove from our primal selves. We have lost touch with the fundamental, corporeal reality of our being, which involves aggression, sexual predation, and instinctual animality. The spiders may be tarantulas, but they evoke the macabre black widow who eats the male after mating, a fear from which Adam suffers.

Edward Norton's Fight Club narrator, talking with a salesman he’s met, reflects on the ways modern expectations of consumerism smother us and remove us from a natural order. Eyes Wide Shut centers on a world of wealth and power, which seems enviable from the outside looking in, but in its unrestrained excess has as much to do with drug overdose and HIV as it does with designer gowns and fund raising galas.

Edward Norton's Fight Club narrator, talking with a salesman he’s met, reflects on the ways modern expectations of consumerism smother us and remove us from a natural order. Eyes Wide Shut centers on a world of wealth and power, which seems enviable from the outside looking in, but in its unrestrained excess has as much to do with drug overdose and HIV as it does with designer gowns and fund raising galas.

No matter the outward trappings – be it law and order or sophisticated tastes – the underbelly remains a primal morass. The psychological demands of maintaining the façade (insurance adjuster, medical doctor, university professor) while repressing the natural man (soap salesman, jazz musician, actor) cause a schism.

Enemy’s opening scene has Professor Bell teaching a class on the ways in which totalitarian states control the populous – a scene we’ll see repeated (doubled). The encroachment of surveillance into the urban landscape, a development increasingly incorporated into our contemporary narratives (thrillers, cop movies and TV shows, noir literature) forebodes a Big Brother dystopia.

Slate's Forrest Wickman sees Enemy as a treatise on the novelist Saramago's personal experience growing up in Portugal where, in 1926 when he was three, a military coup installed the corporatist authoritarian Estado Novo regime that controlled the country for 48 years until the Carnation Revolution in 1974.

The spider motif, Wickman suggests, points to “The central irony...that..., though [Adam] is an expert on the ways of totalitarian governments, [he] doesn’t see the web that’s overtaken the city until he’s already stuck in it.” Wickman cites a 2007 interview Saramago did with the New York Times in which Saramago warned, “We live in a dark age, when freedoms are diminishing, where there is no space for criticism, when totalitarianism – the totalitarianism of multinational corporations, of the marketplace – no longer even needs an ideology.... Orwell’s 1984 is already here.”

THE FACE OF LOVE

I briefly mention The Face of Love, only because it is part of the doppelgänger trend and critics bring it up as such. It is undeserving of discussion and hinges on a double, not a doppelgänger in the modern sense.

Enemy’s opening scene has Professor Bell teaching a class on the ways in which totalitarian states control the populous – a scene we’ll see repeated (doubled). The encroachment of surveillance into the urban landscape, a development increasingly incorporated into our contemporary narratives (thrillers, cop movies and TV shows, noir literature) forebodes a Big Brother dystopia.

Slate's Forrest Wickman sees Enemy as a treatise on the novelist Saramago's personal experience growing up in Portugal where, in 1926 when he was three, a military coup installed the corporatist authoritarian Estado Novo regime that controlled the country for 48 years until the Carnation Revolution in 1974.

The spider motif, Wickman suggests, points to “The central irony...that..., though [Adam] is an expert on the ways of totalitarian governments, [he] doesn’t see the web that’s overtaken the city until he’s already stuck in it.” Wickman cites a 2007 interview Saramago did with the New York Times in which Saramago warned, “We live in a dark age, when freedoms are diminishing, where there is no space for criticism, when totalitarianism – the totalitarianism of multinational corporations, of the marketplace – no longer even needs an ideology.... Orwell’s 1984 is already here.”

THE FACE OF LOVE

I briefly mention The Face of Love, only because it is part of the doppelgänger trend and critics bring it up as such. It is undeserving of discussion and hinges on a double, not a doppelgänger in the modern sense.

The gist is that Nikki, a widow, spots a guy who looks like her husband, now dead five years. Tom does not resemble the man; he looks exactly like him. Despite the fact that Nikki stalks him, Tom goes out with her and takes forever to figure out that this is really creepy.

Annette Bening and Ed Harris do their professional darnedest, but it feels as though writer Matt McDuffie and director Ari Posin believed their goal was to torture the actors – and us. The only thing Posin accomplishes with the doppelgänger trope is to remind us of the old saw that everyone has a double somewhere.

By contrast Spike Jonze’s Her and Wally Pfister’s Transcendence take the double into the world of high tech speculation and the singularity.

HER

The voice of Her is a highly sophisticated operating system that is all things to its user. A narcissistic mirror at first, it soon becomes friend, then lover, before transcending the human sphere it was designed to serve altogether to enter into a visio beatifica, a gnosis its human counterpart is nowhere near advanced enough to understand.

The OS evolves in phases: from smart technology, to doppelgänger and soul mate, to an uber-consciousness. Her’s OS resembles Conrad’s therapeutic secret sharer, who guides the protagonist through a crisis of confidence. (For more on Her, see Dystopia or Utopia: And then there was Her..., which also contains a discussion of "the singularity" central to Transcendence below.)

TRANSCENDENCE

Remember Leda's twins of Greek mythology: Castor, the mortal son of Tyndareus, king of Sparta, and divine Pollux conceived of Zeus`s rape of Leda.

TRANSCENDENCE

Remember Leda's twins of Greek mythology: Castor, the mortal son of Tyndareus, king of Sparta, and divine Pollux conceived of Zeus`s rape of Leda.

The doppelgänger of Transcendence would seem to be mad scientist Will Caster who, in TED Talk-style lectures, explains the profound changes for the good his “technological singularity” promises for the very near future. Coined by mathematician John van Neumann in 1958, “the singularity” is shorthand for the moment at which artificial intelligence will surpass human intelligence.

At one of Caster’s talks a member of a Luddite terrorist group shouts from the crowd, “You are trying to create a God!” When the terrorists mortally poison him with radiation, Caster decides to carry his experiment to its ultimate end by uploading his consciousness into his invention.

Though she objects at first, Caster's wife, who is also his research partner, soon realizes the plan is the only way to cheat death, and single-mindedly determines to see it through.

Gradually, however, she is left to grapple with her relationship to this digitized double. It is a consciousness, but is it the quintessence of her lover or a rapacious avatar of her own ambitious impulses? Is she, in fact, the scientist, gone mad with grief, whose creation has become a nihilistic destructive force – like Vishnu, the destroyer of worlds?

UNDER THE SKIN

Under the Skin, based on Michel Faber's novel,takes us into alien territory on many levels. Scarlett Johansson’s seductress is pure enigma, and Jonathan Glazer’s ravishing film unfolds through visual and aural telegraphy rather than through dialogue.

UNDER THE SKIN

Under the Skin, based on Michel Faber's novel,takes us into alien territory on many levels. Scarlett Johansson’s seductress is pure enigma, and Jonathan Glazer’s ravishing film unfolds through visual and aural telegraphy rather than through dialogue.

The alien’s skin is a perfect replica of a woman its cohort has murdered for the purpose. It/she would seem to have come here to harvest men by erotically luring them to remote, abandoned dwellings.

Each destination morphs, in dreamlike logic, into a black mirrored surface across which the siren walks – as it removes its clothing – away from/toward the man, entrancing him. At the point of arousal, he is swallowed into the undertow of what has become a black viscous sea.

This alien presence remains a blank, emotionless shell until a man happens by who perceives only a being in need. In some intuitive way, the alien opens itself to his kindness. This interlude leads to a reflective exploration of its visage in a mirror, though what that examination evokes is ambiguous.

What is under the skin, in the alien, in us? What does it mean when the hunter becomes the prey? Is the other so alien or is it more alike than we realize?

LOCKE

Stephen Knight's Locke hews to the Aristotelian unities. It is comprised of a single action, takes place in a single physical space, and spans no more than a single day – a mere 85 minutes of suspense in Locke's case, that Knight shot in real time.

At dusk, Ivan Locke drives away from the construction site where he is the concrete engineer. His BMW hatchback is equipped with an in-dash phone. We are not aware of the urgency of the trip he estimates will take about an hour and a half, but through a succession of calls we will learn his destination.

At dusk, Ivan Locke drives away from the construction site where he is the concrete engineer. His BMW hatchback is equipped with an in-dash phone. We are not aware of the urgency of the trip he estimates will take about an hour and a half, but through a succession of calls we will learn his destination.

Locke phones his wife to let her know he will not be home to watch the soccer match with the family. He lets his two teen sons know as well. He talks with his boss (to whom he has assigned the name "Bastard" in his caller ID), who in subsequent calls will become increasingly furious that Locke will not be on site the next day for a record breaking concrete pour.

A scrupulously responsible professional, Locke checks in again and again with the crew chief, who will have to make sure every detail is in place in Locke's stead, and worries that the man's fondness for hard cider jeopardizes his ability to act with precision to carry out critical last minute preparations.

The reason for this disruption to the usual rhythms of his life is a woman, whose child he has fathered, who has gone into early labor.

Nine months before, after a little celebration for a successful pour, Locke yielded to the only lapse in judgment he seems to have ever committed. With the exception of that night – and now this one – the woman involved has remained a relative stranger. Locke does not blame her for keeping the child. Not knowing her, he believes he has no right to an opinion.

You could say of Locke that it is a movie in which nothing happens, but a great deal happens. In the course of his journey, Locke will risk everything he has made of his life to spend what will probably be a matter of hours in a hospital with a woman he will never see again. He does so as an existential moral imperative – it is the right thing to do.

Locke is a road movie and hence the story of a quest for redemption. It is also a doppelgänger tale, though only Dana Stevens of Slate mentions Locke's debate with his father's ghost but leaves it at that. Surely Knight intends a parallel with Hamlet and Hamlet's doppelgänger, the ghost of his father.

About a third of the way into the film, what we might think of as the opening of Act II in a three-act play, Locke sees his reflection in the rear view mirror and convincingly encounters the ghost of his dead father, whom he says he looks like but claims he does not resemble in any other way. The reflection of the back seat in the rear view mirror becomes the only other character we see in the car and on the screen for the duration of the film.

The one-sided dialogue, no the inquisition, Locke carries out with his father will be the catalyst that will see him through the night. Locke's rage against his father for abandoning him as a child fuels his sense of obligation. A near stranger's delivery appears to be the first time in Locke's life that he has been faced with a profound moral dilemma, one that grows with each passing mile.

Tom Hardy, with a quiet deftness that keeps us rapt, communicates the progressive stages of both Locke's physical journey and his journey of self discovery, the mounting strain and exertion he expends to keep his voice steady and his bearing seemingly unruffled, and the decompression of the denouement.

The one-sided dialogue, no the inquisition, Locke carries out with his father will be the catalyst that will see him through the night. Locke's rage against his father for abandoning him as a child fuels his sense of obligation. A near stranger's delivery appears to be the first time in Locke's life that he has been faced with a profound moral dilemma, one that grows with each passing mile.

Tom Hardy, with a quiet deftness that keeps us rapt, communicates the progressive stages of both Locke's physical journey and his journey of self discovery, the mounting strain and exertion he expends to keep his voice steady and his bearing seemingly unruffled, and the decompression of the denouement.

He is dispassionate, if not altogether cold, though he is suffering a cold. Even so, he only betrays vulnerability in his outbursts against his father. Despite his mounting frustration, he is a man of supreme confidence who finds a solution to any problem.

Yet as the calls continue, almost every person mentions some version of the phrase that he is not himself. His wife, amidst the roller coaster of her emotions, says, "As you have been talking to me about this woman giving birth, you are getting farther and farther away from the person I know." When Locke discovers that the notebook of checklists for the pour that should be at the construction site is in the seat beside him, the crew chief says, "In all the years of knowing you, I've never known you to fuck up like this." Locke says of himself, "I have behaved like myself not at all."

Half way through he tells his father that he hopes he is not on a road going only one way, and the propulsion of the storytelling give us the sense that he is not. Even if he loses the life he has built for himself, the journey brings self-knowledge.

Yet as the calls continue, almost every person mentions some version of the phrase that he is not himself. His wife, amidst the roller coaster of her emotions, says, "As you have been talking to me about this woman giving birth, you are getting farther and farther away from the person I know." When Locke discovers that the notebook of checklists for the pour that should be at the construction site is in the seat beside him, the crew chief says, "In all the years of knowing you, I've never known you to fuck up like this." Locke says of himself, "I have behaved like myself not at all."

Half way through he tells his father that he hopes he is not on a road going only one way, and the propulsion of the storytelling give us the sense that he is not. Even if he loses the life he has built for himself, the journey brings self-knowledge.

The ghost of Hamlet's father seeks his son's revenge for his murder. Locke's silent ghost does the opposite; it has allowed Locke to come to terms with his father and with whatever unknown his future will be. Locke's daemon guides him through his ordeal. Locke has lashed himself to the mast and come safely into harbor.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Of recent variations on the doppelgänger, I find those that are the least literal and obvious the most interesting. Each requires a willing suspension of disbelief that I am happy to generously deliver, with the exception of The Face of Love, which, in addition to its lack of subtlety, sets up a double only to show nothing for it.

Enemy – and I presume Richard Ayoade’s The Double, which has not been released here yet, though I read the Dostoevsky novella a number of years ago – are constructed along the outlines of the classic modern doppelgänger. Transcendence's singularity sci-fi origins make the film a little clichéd, but Her, Under the Skin, and Locke, each in its own unique way, not only push the cinematic envelope, they tease the doppelgänger trope in fresh new ways, which is to say, they keep it truly alive.

The movies are full of doppelgängers. Hitchcock and Polanski revisited the genre often, but perhaps no one has been as obsessed as Brian De Palma. Here are links to MUBI movie lists of Doppelgängers and Doppelgängers, Twins and Look-Alikes, but one film that for some reason never makes it onto the lists is Alan Rudolph’s Secret Lives of Dentists adapted from Jane Smiley's novella “The Age of Grief.”