Sometimes happy, sometimes blue.

Glad that I ran into you.

Tell the people that you saw me passing through.”

~~Leonard Cohen, “Passing Through” (written by R. Blakeslee)

“I’m just a station on your way,/I know I’m not your lover.” ~~Leonard Cohen, “Winter Lady”

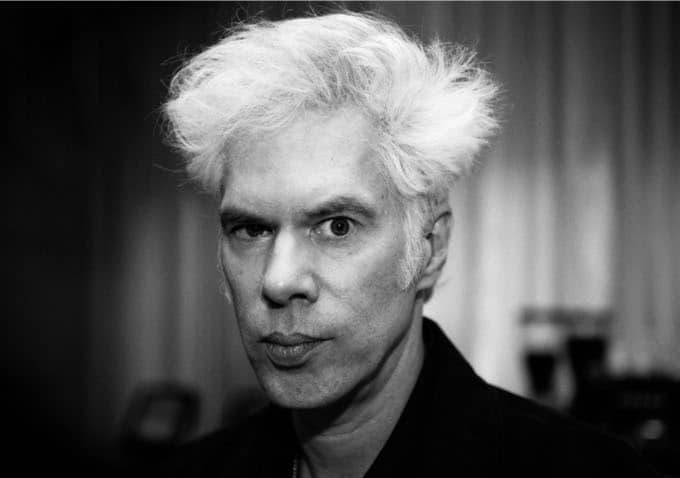

Jim Jarmusch’s vision is quintessentially American, just as Jarmusch himself is quintessentially American: born in middle America (Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio, raised in Akron), a middle child of a German-Irish mother and Czech-German father. Yet though born American, Jarmusch sees America through an alien’s eyes. Jarmusch’s America is tacky, dilapidated, littered and absurd, but it’s got a great soundtrack, and its people are redeemed by each other as they pass through on their quests to become themselves on the one hand and conform to this elusive time and elusive place on the other.

|

| Jim Jarmusch |

Among American directors, I can think of only two who incorporate foreign and foreign-born actors and characters as casually as French, Belgian and various Scandinavian directors do. One is Ramin Bahrani, who was born to Iranian parents in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and has explored the immigrant experience in “Man Push Cart,” “Chop Shop,” and “Goodbye Solo.” The other is Jarmusch, whose casts and crews are typically international.

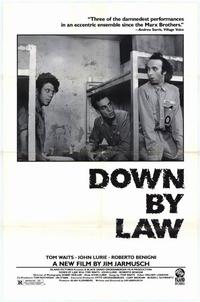

Jarmusch's actors employ a masterful deadpan delivery in the tradition of Buster Keaton, Peter Sellers, and Ben Stein, effected in Jarmusch’s absurdism through John Lurie, Masatoshi Nagase, Johnny Depp, Forest Whitaker, Bill Murray, Isaach de Bankolé, Tom Hiddleston and Tilda Swinton. All encapsulate the essential quality of this particular form of comic genius – that their characters, regardless of the utter absurdity of their situations, retain their dignity and humanity. Often these laconic souls share the stage with a chatterbox like Roberto Benigni’s Bob in “Down by Law”; Youki Kudoh’s Mitsuko and Elizabeth Bracco’s Dee Dee in “Mystery Train”; Benigni’s cabbie in “Night on Earth”; and Mia Wasikowska’s Ava in “Only Lovers Left Alive.”

Jarmusch's actors employ a masterful deadpan delivery in the tradition of Buster Keaton, Peter Sellers, and Ben Stein, effected in Jarmusch’s absurdism through John Lurie, Masatoshi Nagase, Johnny Depp, Forest Whitaker, Bill Murray, Isaach de Bankolé, Tom Hiddleston and Tilda Swinton. All encapsulate the essential quality of this particular form of comic genius – that their characters, regardless of the utter absurdity of their situations, retain their dignity and humanity. Often these laconic souls share the stage with a chatterbox like Roberto Benigni’s Bob in “Down by Law”; Youki Kudoh’s Mitsuko and Elizabeth Bracco’s Dee Dee in “Mystery Train”; Benigni’s cabbie in “Night on Earth”; and Mia Wasikowska’s Ava in “Only Lovers Left Alive.”

STRUCTURE

One might say that nothing much happens in a Jarmusch film, and yet, Jarmusch characters are always on the move – walking the mean streets of New York or scrambling across the swamps of Louisiana, rumbling down the line to Memphis or Machine, motoring along highways, taxiing through metropoles, floating downriver to the spirit world, jetting across oceans or simply moving through the circumscribed contours of a town or a room.

Outside the rooms, Jarmusch’s characters travel. In “Permanent Vacation,” Allie, the modern-day flâneur, performs his peregrination through the streets of downtown Manhattan like a meditation, ready to embark for Paris at the end.

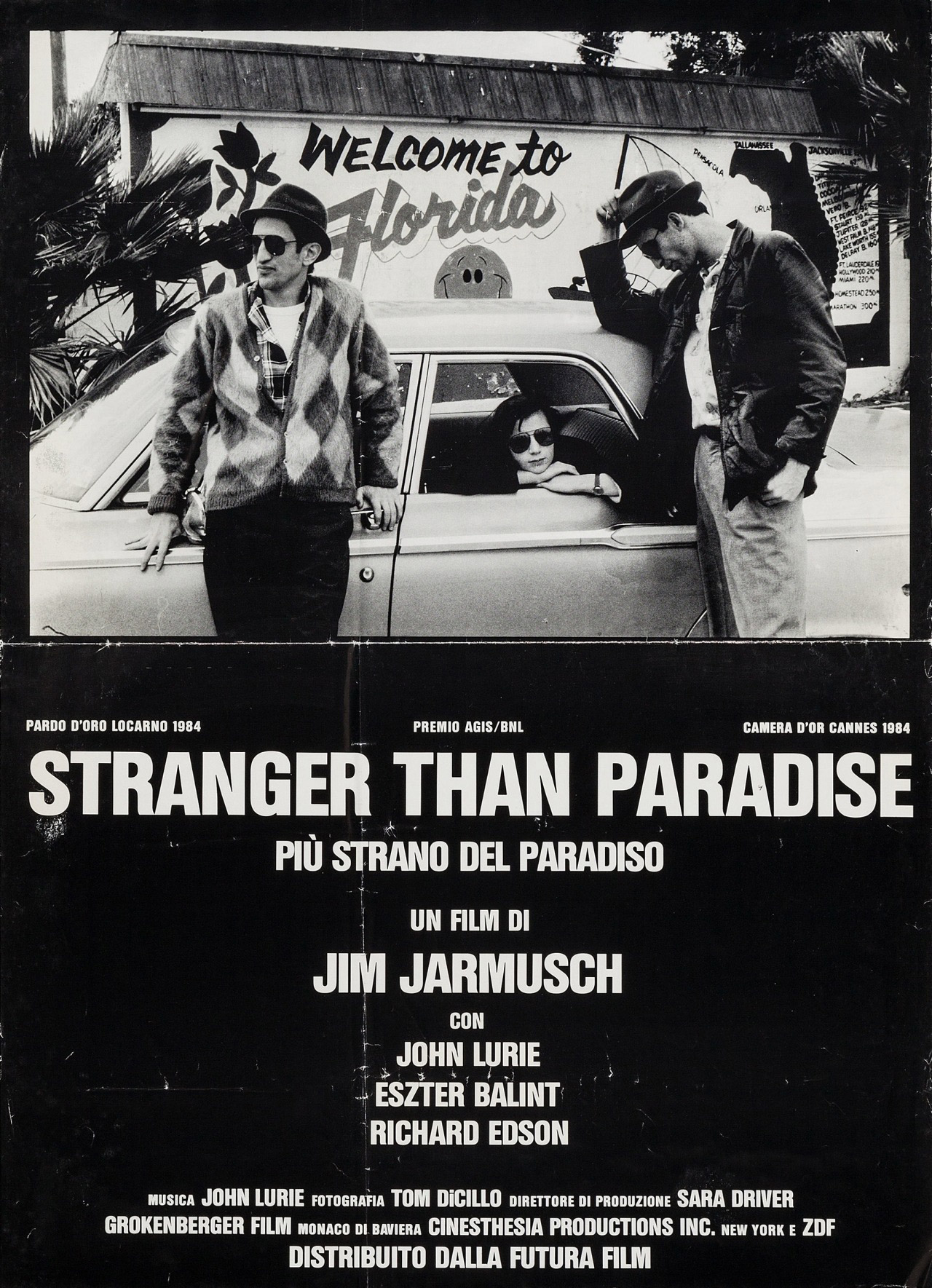

In “Stranger Than Paradise,” Willie and Eddie, fleeing gamblers they've swindled, cruise from the Lower East Side to Cleveland to small town Florida. On their way from New York to Cleveland, Eddie remarks, “You know, it’s funny. You come to someplace new and everything looks just the same.” “No kidding,” Willie concurs. Every town has the same abandoned factories, the same rundown motels, the same suburban neighborhoods, and the same McMansion sub-divisions. In “Down by Law,” the trio of misfits move from the streets of New Orleans to the jailhouse to the bayou, heading for refuge in...Texas maybe...or LA.

In “Mystery Train,” everyone ends up at the Arcade at some point, a not-so-grand hotel of intersections, arrivals and departures. The young couple from Yokohama, Jun and Mitsuko, who arrive by train in Memphis to pay homage to Elvis, Carl Perkins and Sun Records will board again to head to New Orleans and pay their respects to Fats Domino; Luisa will take her husband’s corpse from Memphis back to Rome; Dee Dee will catch the train from Memphis to Natchez; and Johnny, Will and Charlie will flee from Memphis – maybe to Arkansas – to escape the long arm of the law. “You hear that?” “I can hear a train.” “I hear sirens.”

Taken together, “Stranger Than Paradise,” “Down by Law” and the three tales that make up the Arcade Hotel suite that constitutes “Mystery Train” demonstrate a Jarmuschian truth: the ubiquity of human stupidity on the one hand and the willingness to act as one’s brother’s keeper on the other. Through it all, the world is on the move – and keeps on moving in the five more tales that make up “Night on Earth” as Jarmusch taxis through Los Angeles, New York, Paris, Rome, and Helsinki.

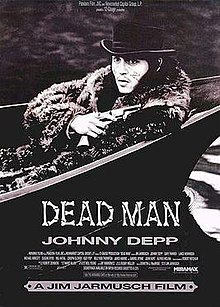

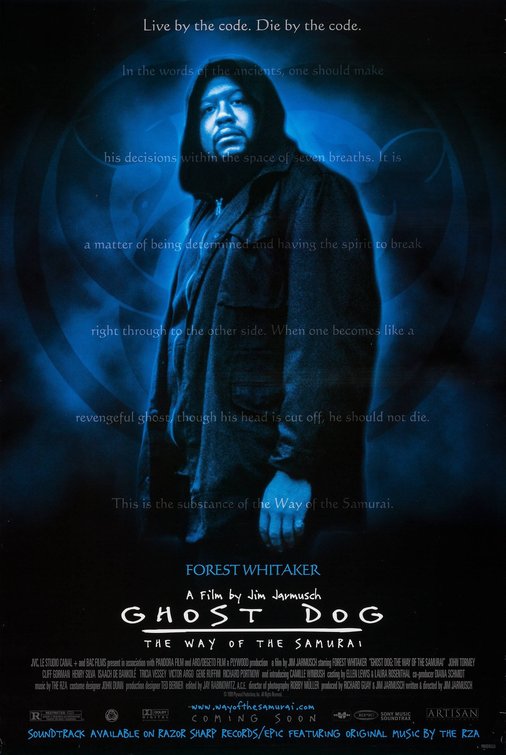

In “Dead Man,” the American doppelganger of William Blake begins his journey west on a steam locomotive from Cleveland to the end of the line in Machine, and then, through the wilderness on horseback to the River Styx and the canoe that will take him to the other side. In “Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai,” somewhere, in a place like Jersey City, a modern-day samurai survives – for a while – by his code and his wits. In “Broken Flowers” a modern-day Don Juan traverses rural Upstate New York and New Jersey by plane, bus and rental car in search of lost time.

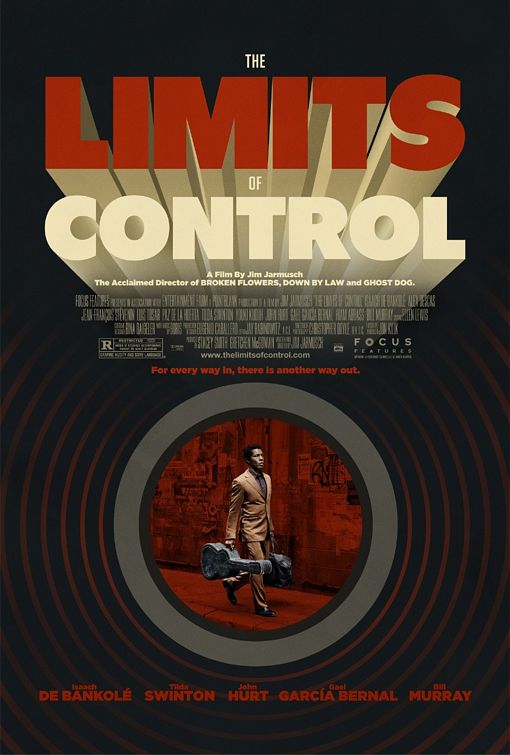

In “The Limits of Control,” Lone Man sets out from urban Madrid, one train after another, until his final guide in a battered pickup takes him to carry out his mission in the desert. Only then can he return to the capital. Vampiric incarnations of the archetypal Adam and Eve rely on jetliners to get from Tangier to Detroit to Tangier in “Only Lovers Left Alive,” and in “Paterson,” a poet named Paterson pilots a bus around Paterson, New Jersey, finding the profound in the quotidian.

Always, Jarmusch films are episodic and deceptively minimalist. One can say of them: this happens, then this happens, then that happens, but they are first and foremost about atmosphere and only secondarily about plot.

This is especially true of his first film, “Permanent Vacation,” which is a mood piece that takes place over the course of a day. His third, “Down by Law,” begins, not so much with two plot lines as with two unrelated characters. Two New Orleanian losers, Zack and Jack, find themselves thrown together through happenstance with a hyper Italian named Bob. Bob proposes an jail break, which sets the trio in motion. At the end, Bob finds sanctuary, and his cohorts find themselves where two roads diverge in a wood. Jack and Zack agree, you go your way and I go mine.

“Mystery Train” tells three distinct stories, and though one character overlaps the second and third stories, otherwise the only connection is that all of the characters, under different circumstances, find themselves at the Arcade Hotel in Memphis. The five stories that make up “Night on Earth” bear no connection geographically or otherwise and no overlap of characters, but they share thematic concerns of the problems of language and misunderstanding caused by surface assumptions based on outward appearances.

“Dead Man” is a more linear story that moves back and forth between the man with a bounty on his head and the bounty hunters pursuing him. Likewise “Ghost Dog,” where Jarmusch has moved from the Wild West to an east coast metropolis and replaced bounty hunters with the mob. The mirroring of William Blake in “Dead Man” allows Jarmusch overtly to explore existential and metaphysical concerns about the intertwined nature of the inner and outer journeys that comprise a life, and “Ghost Dog” allows an exploration of how one creates a context by which to give one’s outward action meaning that informs the inward journey.

“Mystery Train” tells three distinct stories, and though one character overlaps the second and third stories, otherwise the only connection is that all of the characters, under different circumstances, find themselves at the Arcade Hotel in Memphis. The five stories that make up “Night on Earth” bear no connection geographically or otherwise and no overlap of characters, but they share thematic concerns of the problems of language and misunderstanding caused by surface assumptions based on outward appearances.

“Dead Man” is a more linear story that moves back and forth between the man with a bounty on his head and the bounty hunters pursuing him. Likewise “Ghost Dog,” where Jarmusch has moved from the Wild West to an east coast metropolis and replaced bounty hunters with the mob. The mirroring of William Blake in “Dead Man” allows Jarmusch overtly to explore existential and metaphysical concerns about the intertwined nature of the inner and outer journeys that comprise a life, and “Ghost Dog” allows an exploration of how one creates a context by which to give one’s outward action meaning that informs the inward journey.

“Coffee and Cigarettes” is Jarmusch’s least conventional film. Released in 2003, it is series of eleven vignettes, the oldest of which, “Strange to Meet You,” was filmed as a short in 1986. With a few exceptions each takes place in a coffee shop, restaurant, diner or juke joint, often with shots from above so that the checkerboard tablecloths evoke chess boards, as if to suggest that the characters’ slightly combative conversations over coffee and cigarettes are the equivalent of a strategic game of competitive chess. (In “Paterson,” Paterson the poet will watch Doc the barman play chess against himself.)

“Coffee and Cigarettes” is an anomaly in Jarmusch’s more recent work. “Broken Flowers” and “The Limits of Control” are heir to “Dead Man” and “Ghost Dog.” They are obvious quest tales in Joseph Campbell’s classic sense of the Hero’s Journey. “Dead Man” organizes itself around the visionary poet William Blake and the American Myth of the West; “Ghost Dog” around the teachings of the "Hagakure," "The Way of the Samurai." “Broken Flowers” is something of a “Don Juan at Rest” ala John Updike’s Harry Rabbit. The structure of “Only Lovers Left Alive” is dictated by Bram Stoker’s “Dracula,” though it is not without its Jarmuschian detours.

LANGUAGE, DOUBLING, ALLUSION AND PLAIN OL' NAME DROPPING

Again, among the recurring devices Jarmusch employs, one is the attention he accords to the problem of language, translation and miscommunication. (Sofia Coppola’s 2003 “Lost in Translation” deals with similar concerns and shares actor Bill Murray so that I sometimes mistakenly want to attribute it to Jarmusch.) Allusion is also a significant element in the Jarmuschian oeuvre. Jarmusch studied under Nicholas Ray, best known for his 1955 “Rebel Without a Cause,” and worked as Ray's personal assistant during the time that Wim Wenders was filming his 1980 documentary about Ray, “Lightening Over Water.” In “Permanent Vacation,” Allie steps into a movie house showing Ray’s 1960 “The Savage Innocents,” and in “The Limits of Control,” Lone Man passes a movie poster in Spanish for Ray’s 1950 “In a Lonely Place,” but Jarmusch's character Blonde is the figure in the trench coat instead of Dorothy Hughes who co-starred with Humphrey Bogart.

Jarmusch, a student of literature and art history, spent a good part of his youth watching matinee double B-features, a good part of his early adulthood in Paris at the Cinémathèque Française, and, upon his return to New York, worked as a musician. The horses in the racing form in “Stranger Than Paradise” include Late Spring, Passing Fancy and Tokyo Story – all titles of Yasujirō Ozu films.

Doubling is everywhere in Jarmusch-land. Actors cross-populate from film to film. Twins and cousins people the vignettes of "Coffee and Cigarettes." Shared names – between actor and character, between character and musician or cultural icon or literary figure, between one film and another – create a doppelgänger effect that also functions as a kind of Everyman effect. In “Permanent Vacation,” the actor Chris Parker plays Aloysious (Allie) Christopher Parker who ruminates on jazz saxophonist and composer Charlie Parker.

In “Stranger Than Paradise,” the Hungarian-born Willie (John Lurie) has worked to shed his Hungarian-ness, not wanting to be seen as an outsider. “Are you Bela Molnar,” his cousin Eva (Eszter Balint) asks at his door, newly arrived from Budapest. “No… I used to be. Call me Willie, if you have to call me something.” Just as he has chastised his Aunt Lotte (Cecilia Stark), “Speak English, please!” (in vain), when Eva replies in Hungarian, he insists, “Don’t speak Hungarian at all. Only English. All right. While you’re here, only English.”

Willie’s gambling buddy is Eddie (Richard Edson) – “Willie” and “Eddie” are diminutive names formed with the “ie” suffix. It’s not as close a match as Jack and Zack will be in “Down by Law,” but it seems fair to say that these are conscious decisions Jarmusch makes when writing his screenplays.

Misunderstanding sometimes causes hurt, but in Jarmusch’s world, it is usuallly a font of humor. In “Down by Law,” both Jack (John Lurie) and Zach (Tom Waits) are in jail because they have been set up. Ironically, sweet, funny Bob (Roberto Benigni) has actually committed murder, though in self-defense.

Once in the cell with Jack and Zack, the Italian Bob can’t help but be confused as to which name goes with which cellmate. Bob speaks scant English, mostly composed of idiomatic expressions and colloquialisms he has collected in a little notebook, which compounds the difficulty for translation. When Zack tells Bob to “Buzz off,” Bob delights in the sheer sound of it without any sense of what it means. His fondness for the pure sound of language has translated into a love of poetry, and he tries to connect by asking about American poets. He asks if Jack and Zack have read Walt Whitman and Robert Frost. Bob knows them both – albeit in Italian – so that when he has to turn Whitman back into English it comes out “Leaves of Glass.” And then, of course, there’s that road not taken as the backdrop for the final scene.

In “Mystery Train” in the first story “Far from Yokohama,” the night clerk (Screamin' Jay Hawkins) and the bellboy (Cinqué Lee) at the Arcade Hotel can’t understand the Japanese couple (Masatoshi Nagase as Jun and Youki Kudoh as Mitsuko). Dee Dee (Elizabeth Bracco) in the second tale, “A Ghost,” is Johnny’s girlfriend and Charlie’s sister in the third tale, “Lost in Space,” which is confused by Johnny aka Elvis (Joe Strummer), Will (Rick Aviles) and Charlie’s (Steve Buscemi) drunkenness.

Charlie is struck by the fact that Johnny’s friend’s name is William Robinson, the same as the character in the 1960s TV show “Lost in Space” – and the same as Daniel Defoe’s castaway Robinson Crusoe and Johann David Wyss’s shipwrecked Swiss Family Robinson. The TV title and the episode title connote two different meanings of “space”: the colonists of the TV show are lost in outer space; Jarmusch’s protagonists are lost in the spaces of America and in inner space.

Elvis is everywhere in “Mystery Train,” and that second episode, “A Ghost,” will be echoed three movies later (not counting the 1997 concert film) in “Ghost Dog.” The D.J. who punctuates the soundtrack of “Mystery Train,” though we never see him, is the D.J. Zack from “Down by Law” – here transported from New Orleans to Memphis.

Among the stories that compose “Night on Earth,” the problem of communication and misunderstanding between cabbie and fare links the stories. In the New York episode, the cabbie (Armin Mueller-Stahl), who was a clown in his native East Germany, is named Helmut, a common enough name in Germany, but to a New York hipster (Giancarlo Esposito) “a helmet would be, like, you know, like something you wear on your head? …. In English, that'd be like calling your kid ‘Lampshade’.” The irony in the fact that the hipster’s name is Yo Yo (doubled like Dee Dee in “Mystery Train”) is lost on the hipster. Helmut thinks being named after a toy is funny. Frustrated, Yo Yo explains the name has nothing to do with the toy. When Helmut puts the issue to rest saying, “Your name Yo Yo. My name Helmut. Yo Yo, Helmut. It's good,” we get the sense that this kind of good-humored acceptance is utterly necessary to survival as an outsider.

The Paris episode involves two types of otherness. The driver from the Ivory Coast (Isaach De Bankolé) is an immigrant. His fare (Béatrice Dalle) is blind. The cultural differences are twofold: driver and rider differ ethnically on the one hand and in their sensory experience of the world on the other. The conceit revolves around blindness both literal and figurative – what we have or do not have the ability to see and what we choose or do not choose to see.

An encounter on the street in the Paris segment elicits overt xenophobic slurring. “You think you're in your jungle here?” street punks want to know. “We're not from the same jungle, are we? …. These little brothers who come to France, don't they have any respect? .... You from Togo? From Gabon?” “The Ivory Coast.” “Ivory Coast. He's an ‘Ivoirien.’” They play on the word and taunt, “Can't see a thing!’ That explains it! He's an “Y voit rien’,” they pun. It makes sense to include explicit bigotry in a suite of stories about cabbies, for to be the object of bigotry is not only part of the immigrant experience but surely encountered by immigrant taxi drivers the world over.

When the Ivoirien’s fare refuses to get out of the taxi, he discovers she is blind. Now, she is the other. “Must be a real drag being blind?” he says, without a trace of spite or malice. “I can do anything you can and a lot of things you'll never do,” she says defensively. “I'm blind, that's all.” “I don't know any blind people,” he says by way of apology. “I'm curious, that's all.” “I'm just like you. I drink, I eat, I taste things. I listen to music. I feel music. I do whatever I want.” This conviction is at the heart of Jarmusch’s project – that in the face of our myriad differences is the truth of our shared humanity.

Jarmusch uses the doubling of the character played by Johnny Depp with the seminal English poet of the Romatic Age William Blake to stunning metaphysical effect in “Dead Man,” allowing for Depp's character to be simultaneously dead and alive. The odious metalworks owner John Dickinson (Robert Mitchum in his final film role) ironically evokes the great American poet Emily Dickinson who wrote the poem “I’m Nobody! Who are you?” and William Blake’s guide is the Indian Exaybachay who goes by Nobody (Gary Farmer).

Nobody is conceived in the tradition of Chingachgook, who serves as Natty Bumppo’s guide in James Fenimore Cooper’s “The Leather-stocking Tales”; of Ishmael (the name is that of the son of Abraham who is the first of the three patriarchs of Judaism), who narrates Ahab’s tale in Herman Melville’s “Moby-Dick”; of Jim, the runaway slave who travels down the Mississippi with Huck Finn in Mark Twain’s masterwork; of Tonto in "The Lone Ranger"; even of Spock who advises Capt. Kirk in the final frontier. As Tzvetan Todorov observes in “The Conquest of America: The Question of Other,” “the discovery self makes of the other” (Harper and Row, 1984. p. 247). The trope is not unique to American literature. It goes back to the early novel – Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, Robinson Crusoe and Friday – but it finds its greatest expression in the American canon where the native guide becomes the vehicle for the protagonists’ moral awakening.

|

| Johnny Depp as William Blake and Gary Farmer as Nobody in "Dead Man" |

Nobody tells William Blake his story. As a young man he was captured by English soldiers. “I was then taken east in a cage. I was taken to Toronto, then Philadelphia, and then to New York. And each time I arrived in another city, somehow the white men had moved all their people there ahead of me. Each new city contained the same white people as the last, and I could not understand how a whole city of people could be moved so quickly. Eventually, I was taken on a ship across the great sea over to England, and I was paraded before them like a captured animal, an exhibit. And so I mimicked them, imitating their ways, hoping that they might lose interest in this young savage, but their interest only grew. So they placed me into the white man's schools. It was there that I discovered in a book the words that you, William Blake, had written. They were powerful words, and they spoke to me. But I made careful plans, and I eventually escaped. Once again, I crossed the great ocean. I saw many sad things as I made my way back to the lands of my people. Once they realized who I was, the stories of my adventures angered them. They called me a liar. ‘Exaybachay.’ He Who Talks Loud, Saying Nothing. They ridiculed me. My own people. And I was left to wander the earth alone. I am Nobody.”

Poetry is another kind of language, a heightened, figurative language. Certainly, Jarmusch’s work abounds in metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche and irony, what the literary theorist Kenneth Burke called the four master tropes in “A Grammar of Motives” (U of California Press, 1969). Nobody says to William Blake, “It's so strange that you don't remember any of your poetry.” “I don't know anything about poetry,” says William Blake, the accountant. But Nobody does. Bob, the Italian in “Down by Law” does, and in “Paterson,” we will encounter a poet in the here and now, a poet whose quest is not through the mythopoeic Wild West, but through the quotidian streets of Paterson, New Jersey.

Jarmusch uses Yamamoto Tsunetomo’s 18th century samurai treatise “Hagakure” as a structuring device in “Ghost Dog.” The “Konjaku Monogatarishū” – especially the tale of “Rashōmon” with its rumination on the often immoral acts we commit to survive and the trickery of point of view – figures prominently, as well, and is also a reference to Akiri Kurosawa’s 1950 film. As do all Jarmusch films, “Ghost Dog” proceeds episodically, and the episodes are marked by passages from the "Hagakure," the first of which reads: “Serving one’s master is the most fundamental thing for a retainer.” Louie (John Tormey) – note the name – is a mid-level mobster who saved the young Ghost Dog’s life, and fealty to one’s protector is at the core of the samurai’s code. Ghost Dog only communicates with Louie through messages printed in almost microscopic script, folded and attached to his homing pigeons’ legs. Similarly, when we reach “The Limits of Control,” folded messages again will be relayed, only in code. A miscommunication causes events to go awry, putting Ghost Dog on the final path of Bushido, the way of honor until death. A summation of the Bushido philosophy of honor and reputation above all else is bound up in the saying, "I have found the way of the warrior is death."

Poetry is another kind of language, a heightened, figurative language. Certainly, Jarmusch’s work abounds in metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche and irony, what the literary theorist Kenneth Burke called the four master tropes in “A Grammar of Motives” (U of California Press, 1969). Nobody says to William Blake, “It's so strange that you don't remember any of your poetry.” “I don't know anything about poetry,” says William Blake, the accountant. But Nobody does. Bob, the Italian in “Down by Law” does, and in “Paterson,” we will encounter a poet in the here and now, a poet whose quest is not through the mythopoeic Wild West, but through the quotidian streets of Paterson, New Jersey.

Jarmusch uses Yamamoto Tsunetomo’s 18th century samurai treatise “Hagakure” as a structuring device in “Ghost Dog.” The “Konjaku Monogatarishū” – especially the tale of “Rashōmon” with its rumination on the often immoral acts we commit to survive and the trickery of point of view – figures prominently, as well, and is also a reference to Akiri Kurosawa’s 1950 film. As do all Jarmusch films, “Ghost Dog” proceeds episodically, and the episodes are marked by passages from the "Hagakure," the first of which reads: “Serving one’s master is the most fundamental thing for a retainer.” Louie (John Tormey) – note the name – is a mid-level mobster who saved the young Ghost Dog’s life, and fealty to one’s protector is at the core of the samurai’s code. Ghost Dog only communicates with Louie through messages printed in almost microscopic script, folded and attached to his homing pigeons’ legs. Similarly, when we reach “The Limits of Control,” folded messages again will be relayed, only in code. A miscommunication causes events to go awry, putting Ghost Dog on the final path of Bushido, the way of honor until death. A summation of the Bushido philosophy of honor and reputation above all else is bound up in the saying, "I have found the way of the warrior is death."

|

| Forest Whitaker as Ghost Dog in "Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai" |

“Coffee and Cigarettes,” it is interesting to note, opens to the sound of The Kingsmen's “Louie Louie.” The eleven segments that make up “Coffee and Cigarettes” are filled with cousins (in “Cousins,” the two cousins – one of whom is named Cate – are both played by Cate Banchett) and twins, and twins will inhabit a dream sequence in "Paterson." The vignette entitled “Twins” includes a disquisition on Elvis’s evil twin. In “Jack Shows Meg His Tesla Coil,” the actors play themselves, and Jack Black shows Meg Black his replica Tesla coil while explaining the thwarted achievements of Nikola Tesla, which could have transformed the globe into an ecological miracle.

The Don Johnston "with a 't'" (Bill Murray) of “Broken Flowers” is Don Juan (both Gabriel Téllez’s and Byron’s), Don Johnson (best known for his role in the television series “Miami Vice”), and perhaps the father of a teenage son as well, at least so the pink letter in red ink that comes from the tappity tap tap of a manual typewriter on the soundtrack we hear as the film opens would have it. When the screen comes into focus, we follow the letter’s journey from typewriter to letter box to mail van through sorting machines until finally, it is in a postal carrier’s bag and finds its destination in Don Johnston’s letter slot. The letter’s path parallels the peripatetic nature of Jarmusch’s characters – though without the characters' intentionality. Throughout the montage and throughout the film, the Greenhornes’ “There Is an End” plays, spinning the thematic thread of ephemerality.

Mostly Don sits motionless on his living room sofa, listening to his record player or watching TV. We can assume from a remark Don makes about Ethiopian coffee that Don’s neighbor Winston (Jeffrey Wright), an amateur sleuth, and his wife (Heather Simms) are immigrants. Winston presses the laconic Don to investigate. “You need to treat this as a sign.” “What kind of sign?” Don wants to know. “Of the direction of your life. Of this present moment. You need to solve this mystery….”

|

| Bill Murray as Don Johnston in "Broken Flowers" |

“The Limits of Control” is something of a latter-day Medieval morality play, an allegorical drama in which the characters personify moral qualities, e.g. charity, vice, or abstractions, e.g. death, youth. The protagonist is typically an Everyman who encounters characters who are personifications of moral attributes of good and evil. It is up to him to choose redemption over ruination.

The influence of “Last Year at Marienbad,” the work that grew out of a collaboration between New Novel writer Alain Robbe-Grillet and New Wave director Alain Resnais is everywhere in Jarmusch, but nowhere as conspicuous as in “The Limits of Control.” In both, the unnamed characters move through dreamlike-scapes – Marienbad’s château corridors and garden grounds in the former; the low mountain ranges of Seville, Almería, and into the Tabernas desert in the latter.

Only three main characters interact in “Marienbad.” In the screenplay, the woman is referred to as "A," the man who insists he met her at Marienbad the year before is "X," and the man who may be her husband is "M." Periodically, the men play a Nim-like mathematical game of strategy with wooden matches.

In “The Limits of Control,” there are no actual names either. We follow Lone Man (Isaach de Bankolé) – the appellation recalling Sergio Leone’s Man with No Name – on his mission. His first rendezvous is with Creole (Alex Descas) who translates for French (Jean-François Stévenin): “Use your imagination and your skills. Everything is subjective. He who thinks he is bigger than the rest must go to the cemetery. There he will see what life really is. It’s a handful of dust. La vida no vale nada. Diamonds are a girl’s best friend.” French says, but Creole does not translate, “The universe has no center and no edges. Reality is arbitrary.” Upon his approach Creole has asked – rhetorically – “You don’t speak Spanish, right?" and at each station it will be asked again, as well as some part of this cryptic incantation, one contact after another.

The influence of “Last Year at Marienbad,” the work that grew out of a collaboration between New Novel writer Alain Robbe-Grillet and New Wave director Alain Resnais is everywhere in Jarmusch, but nowhere as conspicuous as in “The Limits of Control.” In both, the unnamed characters move through dreamlike-scapes – Marienbad’s château corridors and garden grounds in the former; the low mountain ranges of Seville, Almería, and into the Tabernas desert in the latter.

Only three main characters interact in “Marienbad.” In the screenplay, the woman is referred to as "A," the man who insists he met her at Marienbad the year before is "X," and the man who may be her husband is "M." Periodically, the men play a Nim-like mathematical game of strategy with wooden matches.

In “The Limits of Control,” there are no actual names either. We follow Lone Man (Isaach de Bankolé) – the appellation recalling Sergio Leone’s Man with No Name – on his mission. His first rendezvous is with Creole (Alex Descas) who translates for French (Jean-François Stévenin): “Use your imagination and your skills. Everything is subjective. He who thinks he is bigger than the rest must go to the cemetery. There he will see what life really is. It’s a handful of dust. La vida no vale nada. Diamonds are a girl’s best friend.” French says, but Creole does not translate, “The universe has no center and no edges. Reality is arbitrary.” Upon his approach Creole has asked – rhetorically – “You don’t speak Spanish, right?" and at each station it will be asked again, as well as some part of this cryptic incantation, one contact after another.

|

| Isaach de Bankolé as Lone Man in "The Limits of Control" |

At the next assignation, Violin (Luis Tosar) asks, “Are you interested in music by any chance? I believe that musical instruments, especially those made out of wood – cellos, violins, guitars – I believe that they resonate, musically, even when they are not being played. They have a memory. Every note that’s ever been played on them is still inside of them resonating in the molecules of the wood.”

Nude (Paz de la Huerta) asks, “Do you like sex?” and later, “Do you like Schubert by any chance? ” Blonde (Tilda Swinton) asks, “Are you interested in film by any chance? I really like old films. …. The best films are like dreams you’re never sure you’ve really had. I have this image in my head of a room full of sand, and a bird flies towards me, and dips its wing into the sand. And I honestly have no idea whether this image came from a dream or a film. Sometimes I like it in films when people just sit there not saying anything.”

Nude (Paz de la Huerta) asks, “Do you like sex?” and later, “Do you like Schubert by any chance? ” Blonde (Tilda Swinton) asks, “Are you interested in film by any chance? I really like old films. …. The best films are like dreams you’re never sure you’ve really had. I have this image in my head of a room full of sand, and a bird flies towards me, and dips its wing into the sand. And I honestly have no idea whether this image came from a dream or a film. Sometimes I like it in films when people just sit there not saying anything.”

|

| Tilda Swinton as Blonde in "The Limits of Control" |

Molecules (Youki Kudoh) asks, “Are you interested in science by any chance? I’m interested in molecules. The Sufis say each one of us is a planet spinning in ecstasy. But I say, each one of us is a set of shifting molecules spinning ecstasy." In "Paterson," the poet will observe, "I go through trillions of molecules that move aside to make way for me while on both sides trillions more stay where they are."

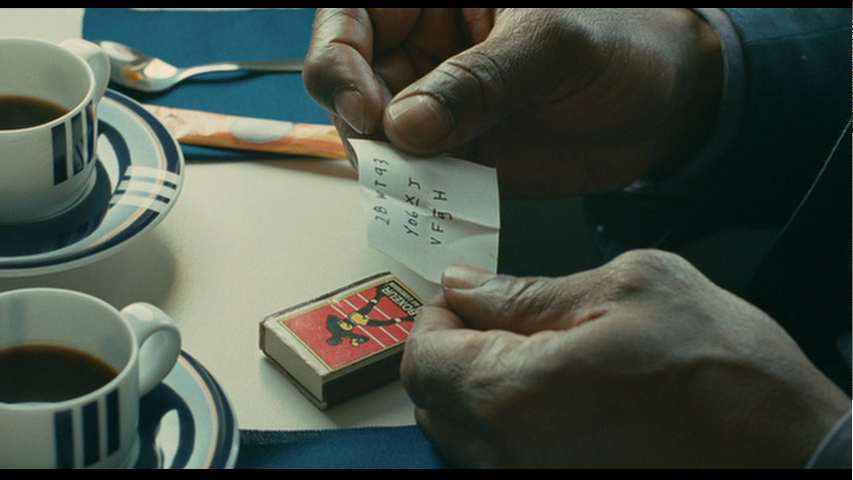

"In the near future," Molecules continues, "worn out things will be made new again by reconfiguring their molecules. A pair of shoes. A tire. Molecular detection will also allow the determination of an object’s physical history. This matchbox, for example. Its collection of molecules could indicate everywhere it’s ever been. They could do it with your clothes. Or even with your skin, for that matter.” Then in Japanese she says, “The universe has no center and no edges.”

"In the near future," Molecules continues, "worn out things will be made new again by reconfiguring their molecules. A pair of shoes. A tire. Molecular detection will also allow the determination of an object’s physical history. This matchbox, for example. Its collection of molecules could indicate everywhere it’s ever been. They could do it with your clothes. Or even with your skin, for that matter.” Then in Japanese she says, “The universe has no center and no edges.”

|

| Youki Kudoh as Molecules in "The Limits of Control" |

Guitar (John Hurt) asks, as have the others, “You don’t speak Spanish, right? No. I don’t speak Spanish, either. Except maybe when I’m in Spain. Would one still call those ‘bohemians’?” he wonders about the flamenco artists Lone Man is watching. “My grandfather was Bohemian. You know, in the Prague sense. I strongly doubt that he would have had any bloody sympathy for those kinds of bohemians. And then of course, they are often the true artists, are they not? Are you interested in art by any chance? Maybe painting perhaps? Yes. Well, as we were discussing, the derivation of the usage of bohemian – in reference to artists or artistic types – wasn’t that it? I don’t know the origin exactly. Of course there’s Puccini’s ‘La Bohème.’ That’s based on the French book ‘Scènes de la vie de bohème.’ Probably published mid-19th century. There was an oddly beautiful Finnish film, some years ago, based on the book. But where the use of ‘bohemian’ or ‘bohème’ in French came from to begin with I can only speculate.” He’s brought Lone Man a guitar and tells him, “You do know that this guitar was owned and played by Manuel el Sevillano. It was recorded on a wax cylinder in the 1920s, believe it or not. God only knows whatever happened to that. Been nice talking with you. As they say, ‘La vida no vale nada.’ Los Americanos!”

|

| Isaach de Bankolé as Lone Man in "The Limits of Control" |

Finally, Lone Man is met by Mexican (Gael García Bernal) who has brought Driver (Hiam Abbass) who will deliver Lone Man to the object of his quest – American (Bill Murray). Mexican tells him, “The old men in my village used to say, ‘Everything changes by the color of the glass you see it through.’ You think that’s true? Everything's imagined. Do you notice reflections? For me, sometimes the reflection is far more present than the thing being reflected. Are you interested in hallucinations, by any chance? Have you ever tried peyote? Do you know who the Huicholes are? They wear mirrors around their necks. And they play violins. Handmade violins. With only one string.”

Seven stations. At each rendezvous Lone Man performs a short t’ai chi ch’uan ritual. At each he will have two espressos only one of which he will drink. At each a guide will give him a matchbox – red exchanged for blue, blue for red – in which he will find a folded, coded message that, once read, he will roll into a pill and swallow before boarding the next train.

Seven stations. At each rendezvous Lone Man performs a short t’ai chi ch’uan ritual. At each he will have two espressos only one of which he will drink. At each a guide will give him a matchbox – red exchanged for blue, blue for red – in which he will find a folded, coded message that, once read, he will roll into a pill and swallow before boarding the next train.

|

| Isaach de Bankolé as Lone Man in "The Limits of Control" |

With its centuries old vampires, “Only Lovers Left Alive” affords Jarmusch the opportunity for allusions galore. The names alone provide Biblical references – Adam (Tom Hiddleston) in Detroit and Eve (Tilda Swinton) in Tangier are the married lovers of the title. They are also lovers of culture, discerning collectors of fine things – vintage guitars, fine violins, first editions, vinyl recordings, cut crystal, a 1982 buttressed Jaguar XJ-S luxury grand touring car – who continue to see the importance of knowing Latin binomial nomenclature. Their homes are littered with portraits of lost friends – great writers and artists and thinkers.

Adam, using the alias “Dr. Faust,” frequents a Detroit blood bank overseen by a Dr. Watson (Jeffrey Wright). Eve’s old friend Christopher Marlowe (John Hurt) purportedly faked his death in 1593 and now lives under the protection of a Tangier local (Slimane Dazi).

Not only do art, literary, musical and philosophical references abound in Jarmusch, references to science take on increasing importance: in the name-dropping of the cabbie’s imagined Genius Hotel in the Rome segment of “Night on Earth” (trysting in a room between Leonardo da Vinci and Einstein; meeting Dante Aligheri, Shakespeare, and Newton; introducing Beethoven to Charlie Parker), and in “Only Lovers Left Alive,” in Eve’s library* – a marvel of world literature with editions that could not otherwise be found outside the al-Qarawiyyin library, the Library of Congress or the Bibliothèque nationale de France – and Adam’s wall of friends** long lost through the centuries. Adam admires Pythagoras, Galileo, Copernicus and Newton, but his real hero is the Serbian inventor Nicola Tesla.

Whereas Jack has built a replica Tesla coil in “Jack Shows Meg His Tesla Coil” in “Coffee and Cigarettes,” Adam has realized Tesla’s dream of a wireless power transfer generator to electrify his Detroit house off the grid, and he’s built a Tesla flux capacitor to run his Jaguar without fossil fuel. Taken together Jarmusch's doubling and allusions add up to an interweaving, not only of multiple strands within a single film but of the entire oeuvre itself – even an entwining of the whole of artistic, philosophical and scientific inquiry.

THE QUEST AND AMERICA

Pauline Kael called “Stranger Than Paradise” “a punk picaresque,” and indeed, Jarmusch's films involve rogues on the road – dreamers, losers, jailbirds on the lam, settlers, immigrants, tourists, hitmen, Lotharios, vampires, cabbies, busmen – all aliens, outsiders navigating against a vaguely defined world of consumer capitalism – ominously lurking offstage – of which we only see the detritus within his frame. Even with their vaudevillian interludes of physical comedy, there is a quiet about a Jarmusch film – spaces to be filled, rooms – yet without a sense of claustrophobia. And there’s always the road outside.

Adam, using the alias “Dr. Faust,” frequents a Detroit blood bank overseen by a Dr. Watson (Jeffrey Wright). Eve’s old friend Christopher Marlowe (John Hurt) purportedly faked his death in 1593 and now lives under the protection of a Tangier local (Slimane Dazi).

Not only do art, literary, musical and philosophical references abound in Jarmusch, references to science take on increasing importance: in the name-dropping of the cabbie’s imagined Genius Hotel in the Rome segment of “Night on Earth” (trysting in a room between Leonardo da Vinci and Einstein; meeting Dante Aligheri, Shakespeare, and Newton; introducing Beethoven to Charlie Parker), and in “Only Lovers Left Alive,” in Eve’s library* – a marvel of world literature with editions that could not otherwise be found outside the al-Qarawiyyin library, the Library of Congress or the Bibliothèque nationale de France – and Adam’s wall of friends** long lost through the centuries. Adam admires Pythagoras, Galileo, Copernicus and Newton, but his real hero is the Serbian inventor Nicola Tesla.

Whereas Jack has built a replica Tesla coil in “Jack Shows Meg His Tesla Coil” in “Coffee and Cigarettes,” Adam has realized Tesla’s dream of a wireless power transfer generator to electrify his Detroit house off the grid, and he’s built a Tesla flux capacitor to run his Jaguar without fossil fuel. Taken together Jarmusch's doubling and allusions add up to an interweaving, not only of multiple strands within a single film but of the entire oeuvre itself – even an entwining of the whole of artistic, philosophical and scientific inquiry.

|

| Tom Hiddleston as Adam and Tilda Swinton as Eve in "Only Lovers Left Alive" |

Pauline Kael called “Stranger Than Paradise” “a punk picaresque,” and indeed, Jarmusch's films involve rogues on the road – dreamers, losers, jailbirds on the lam, settlers, immigrants, tourists, hitmen, Lotharios, vampires, cabbies, busmen – all aliens, outsiders navigating against a vaguely defined world of consumer capitalism – ominously lurking offstage – of which we only see the detritus within his frame. Even with their vaudevillian interludes of physical comedy, there is a quiet about a Jarmusch film – spaces to be filled, rooms – yet without a sense of claustrophobia. And there’s always the road outside.

Whatever the narrative structure, whatever the setting, the quest journey, with its stations along the way, is central to the Jarmusch project. In “Stranger Than Paradise,” Willie and Eddie and Eva have all come to look for America. In “Down by Law,” Jack and Zack and Bob are looking for freedom and with it America, too. Mitsuko and Jun have made a pilgrimage from Yokohama to Memphis in “Mystery Train” to pay homage to Elvis, Carl Perkins and Sun Records, the label founded by Sam Phillips in 1952 that went on to record the definitive soundtrack for a distinct American era.

In “Stranger Than Paradise,” Eva has come from Hungary presumably in search of a better life. She leaves Willie and Eddie a note in the seedy Florida motel room. “I hate America and all Americans,” it says, especially, she hates Willie and Eddie. The note says she’s gone to the airport to go back to Budapest, but at the airport, Eva changes her mind. Not knowing that, Willie has a sense of responsibility to bring her back.

Periodically, throughout John Lurie’s original soundtrack for “Stanger Than Paradise,” Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’s “I Put a Spell on You” emanates from Eva’s tape player. Like the lover in the song, America tempts and entices and doesn’t care if we don’t like what we find.

“Dead Man,” “Ghost Dog,” “Broken Flowers” and “The Limits of Control” are obvious quest stories. William Blake and Ghost Dog embark on spiritual quests, the final leg of which is death. William Blake with his guide Nobody; Ghost Dog with the “Hagakure” teachings; Don with his Sherlock, Winston; and Lone Man with his attendants at each station – Jarmusch's dramatis personae must undertake complicated journeys along which they must overcome obstacles, but, as Van Morrison sings in "Checkin' It Out," "There are guides and spirits all along the way/Who will befriend us." The goal of the quest is not the object or person it ostensibly seeks, but rather the transformation of the one undertaking it.

In “Broken Flowers,” Winston asks Don to make a list of the five women most likely to have authored the letter, then catches Don off guard by not only preparing an itinerary, but making all the necessary travel arrangements – “Booked reservations, rental cars. …. I even got maps. Everything you need.” Don is cemented in inertia, and suggests that if Winston is so gung ho, why doesn't he go instead. “I’ve merely prepared the strategy,” Winston explains. “Only you can solve the mystery.”

Jarmusch is master of the modern spiritual quest, an explorer of the multivariants of freedom. The true quest remains unconditional in its mystery and magnetism for he who would make the sacrifice to renounce quotidian responsibility to become that archetypal stranger in a strange land.

|

| Bill Murray as Don Johnston in "Broken Flowers" |

In the segment titled “Renée” in "Coffee and Cigarettes," Renée French chastises an eager waiter for refilling her coffee: “I had the right color, right temperature, it was just right.” This could be the human conundrum – we can’t seem to get it just right.

“You on a road trip,” Don asks the young man he's spotted at the station when he gets back home. “Yeah. Something like that.” “You a gangster?” the young man asks. “No. I wish. No, I was, I was in computers. Computers and girls.” “I’m interested in philosophy,” the young man says. “Philosophy and girls. You have any, like, philosophical tips or anything for a guy on a kind of road trip?” “Well, the past is gone. I know that,” Don tells him. “The future isn’t here yet, whatever it’s going to be. So, all there is is – is this. The present. That’s it. Are you a Buddhist?” Don asks. “No. Are you?” “I’m not sure yet,” Don replies, and then apologizes. “I’m sorry. That’s the best I have to offer at the moment.”

|

| Adam Driver as the poet Paterson in "Paterson" |

*The Books of Eve (partial list)

Thanks to Sofia da Costa of "Film Flare: Musings on Film & Literature"

“Los Pequeños Poemas” by Ramón De Campoamor, 1871

“Endgame” by Samuel Beckett, 1957

“Infinite Jest” by David Foster Wallace, 1996

“Don Quixote” by Miguel De Cervantes, 1605

“The Temple of the Golden Pavilion” by Yukio Mishima, 1956

"Madame Bovary" by Gustave Flaubert

“The Bastard of Istanbul” by Elik Shafak, 2006

“Basquiat,” edited by Sam Keller and Dieter Buchhart, 1996

“Mrs. Dalloway” by Virginia Woolf, 1925

“The Ambassadors” by Henry James, 1903

“Les Anglais au Pole Nord” by Jules Verne, 1864

“L'Orlando Furioso” by Ludovico Ariosto, 1516

“La Creazione di Adamo e di Eva” in “Porta Del Paradiso, XV” by Lorenzo Ghibeti

“The Bastard of Istanbul” by Elik Shafak, 2006

“Basquiat,” edited by Sam Keller and Dieter Buchhart, 1996

“Mrs. Dalloway” by Virginia Woolf, 1925

“The Ambassadors” by Henry James, 1903

“Les Anglais au Pole Nord” by Jules Verne, 1864

“L'Orlando Furioso” by Ludovico Ariosto, 1516

“La Creazione di Adamo e di Eva” in “Porta Del Paradiso, XV” by Lorenzo Ghibeti

"The Gates of Paradise: Lorenzo Ghiberti's Renaissance Masterpiece," edited by Gary M. Radke, Andrew Butterfield and Margaret Haines, 2007

“Zwischen zwei Revolutionen: Der Geist der Schinkelzeit (1789- 1848)” by Ernst Heilborn, 1927

“The Metamorphosis” by Frank Kafka, 1916

“Zwischen zwei Revolutionen: Der Geist der Schinkelzeit (1789- 1848)” by Ernst Heilborn, 1927

“The Metamorphosis” by Frank Kafka, 1916

**Adam's Wall of Friends and Heroes

Thanks to the blog site "Dracula: History and Myth"

Joe Strummer

Johann Sebastian Bach

Claire Denis

Mary Wollstonecraft

Aki Kaurismäki

Bo Diddley

Franz Schubert

Chrissie Hynde

Franz Kafka

Edgar Allen Poe

Bruce Lee

RZA (appeared in "Coffee and Cigarettes" and "Ghost Dog: Way of the Samurai")

Screamin’ Jay Hawkins (appeared in "Mystery Train")

Gustav Mahler

Henry Purcell

Tom Waits (music for "Night on Earth," appeared in Down by Law" and "Coffee and Cigarettes" and played Renfield in Francis Ford Copalla's "Bram Stoker’s Dracula")

Charles Baudelaire

Luis Buñuel

William S. Burroughs

Sitting Bull

Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning

Robert Johnson

Buster Keaton

Nikola Tesla

Rumi

William Blake (see "Dead Man")

Arthur Rimbaud

Hedy Lamarr

Patti Smith

Charley Patton

Emily Dickinson

Jean-Michel Basquiat (Jeffrey Wright played Basquiat in the biopic)

Robby Müller (Jim Jarmusch’s cinematographer for "Down by Law," "Mystery Train," "Dead Man," "Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai," and the “Twins” segment of "Coffee and Cigarettes")

John Coltrane

Mark Twain

Isaac Newton

Marcel Duchamp

Fritz Lang

Naomi Klein

Frank Zappa

Iggy Pop (appears "Dead Man" and "Coffee and Cigarettes" and is the subject of Jarmusch's upcoming documentary about Iggy and the Stooges)

Thelonious Monk

Harpo Marx

Susan Sontag

Black Elk

Rodney Dangerfield

Christopher Marlowe

Geronimo

Samuel Beckett

Jane Austen

John Keats

Oscar Wilde

Jimi Hendrix

Nicholas Ray

Hank Williams

Billie Holiday

Neil Young (music for "Dead Man" and Jarmusch did concert film: Neil Young and Crazy Horse: Year of the Horse)

Johann Sebastian Bach

Claire Denis

Mary Wollstonecraft

Aki Kaurismäki

Bo Diddley

Franz Schubert

Chrissie Hynde

Franz Kafka

Edgar Allen Poe

Bruce Lee

RZA (appeared in "Coffee and Cigarettes" and "Ghost Dog: Way of the Samurai")

Screamin’ Jay Hawkins (appeared in "Mystery Train")

Gustav Mahler

Henry Purcell

Tom Waits (music for "Night on Earth," appeared in Down by Law" and "Coffee and Cigarettes" and played Renfield in Francis Ford Copalla's "Bram Stoker’s Dracula")

Charles Baudelaire

Luis Buñuel

William S. Burroughs

Sitting Bull

Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning

Robert Johnson

Buster Keaton

Nikola Tesla

Rumi

William Blake (see "Dead Man")

Arthur Rimbaud

Hedy Lamarr

Patti Smith

Charley Patton

Emily Dickinson

Jean-Michel Basquiat (Jeffrey Wright played Basquiat in the biopic)

Robby Müller (Jim Jarmusch’s cinematographer for "Down by Law," "Mystery Train," "Dead Man," "Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai," and the “Twins” segment of "Coffee and Cigarettes")

John Coltrane

Mark Twain

Isaac Newton

Marcel Duchamp

Fritz Lang

Naomi Klein

Frank Zappa

Iggy Pop (appears "Dead Man" and "Coffee and Cigarettes" and is the subject of Jarmusch's upcoming documentary about Iggy and the Stooges)

Thelonious Monk

Harpo Marx

Susan Sontag

Black Elk

Rodney Dangerfield

Christopher Marlowe

Geronimo

Samuel Beckett

Jane Austen

John Keats

Oscar Wilde

Jimi Hendrix

Nicholas Ray

Hank Williams

Billie Holiday

Neil Young (music for "Dead Man" and Jarmusch did concert film: Neil Young and Crazy Horse: Year of the Horse)