Of the word being made into flesh.

Oh chosen love, Oh frozen love

Oh tangle of matter and ghost

Oh darling of angels, demons and saints

And the whole broken-hearted host

Gentle this soul. Gentle this soul.

~Leonard Cohen, "The Window"

Every rave about Paolo Sorrentino's The Great Beauty is an understatement. Set in Rome, the Eternal City, The Great Beauty exudes what we traditionally mean by "culture" and "civilization." Yet that centuries’ worth of civilization is juxtaposed with celebrity and trivial amusements, pettiness and hypocrisy. We mortals surround ourselves with art, music, literature, gardens, philosophy, religion, architecture – all attempts to elevate the human condition above the quotidian. We seek THE great beauty that will transport us into the divine, and when we fail to transcend, we are seduced by the earthly. We turn to diversion to forestall our fears, muffle our knowledge that we are but a speck in the universe. As Ingmar Bergman’s Antonius Block observes in The Seventh Seal, “We carve an idol out of our fear and call it God.”

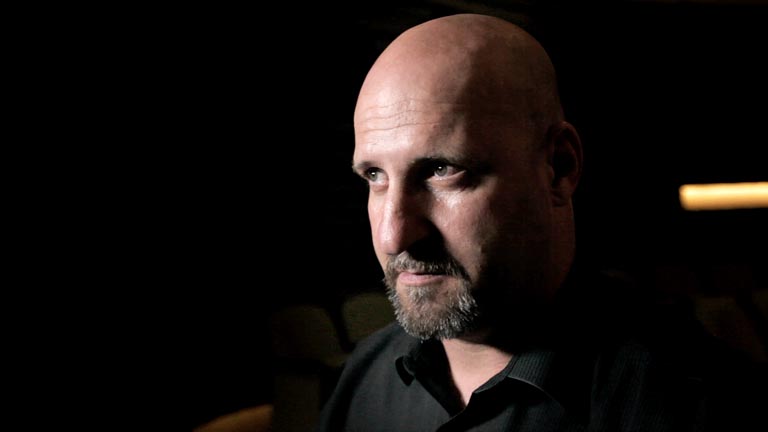

Our protagonist, Jep Gambardella -- marvelously realized by Toni Servillo -- is a sybarite we meet celebrating his 65th birthday. As the film leisurely ambles past the monuments of Rome, like a 19th century Parisian flâneur, Jep parties, banters, seduces, and remembers things past -- a carefree childhood and an early love affair with the young woman he thinks of as the great beauty he lost. The reality, of course, is that she is only "the great beauty" in Wordsworth's "emotion recollected in tranquility," in the abstraction of art and myth. The flesh and blood human being would have disappointed.

We flesh and blood human beings are all failures – even those we place in the pantheon of the greats were flawed mortals like ourselves. We all long to be great, but we settle. After his novel’s modest success, Jep settled on becoming the see-and-be-seen man about town, "King of the High Life," who can make or break the success of a party.

The film is an obvious homage to Fellini and la dolce vita. In some ways, Sorrentino is approaching the same panoramic and cosmic questions that Terrence Malick explores in Tree of Life, but by looking at the human condition in the vastness of time and space through the lens of the absurd Sorrentino succeeds, whereas Malick arguably fails by taking himself too seriously. Jep can be munificent and sardonic by turns, yet despite his hedonistic life, he continues to be a seeker after truth.

Everything about this meditation on life and dying, youth and aging, the sublime and the ridiculous is gorgeous. The camera caresses Rome accompanied by a lush, spellbinding original score by Lele Marchitelli interspersed with David Lang's "I Lie" and "World to Come IV"; Arvo Pärt's piece based on Robert Burns's poem "My Heart's in the Highlands"; Vladimir Martynov's "The Beatitudes"; Zbigniew Preisner's "Dies Irae" from Requiem for My Friend; John Tavener's "The Lamb"; the "II. Adagio" from Georges Bizet's Symphony in C Major; the "III. Lento: Cantabile-semplice" from Henryk Górecki's Symphony No. 3; Magister Perotinus's "Beata Viscera," a conductus celebrating the mystery of the Virgin Mary; and "Water from the Same Source" by Rachel's. This haunting sea of music is juxtaposed with a dizzying club mix of electro-pop, house music and Merengue.

In an interview with Jean Gili, Sorrentino explained that "In thinking about this film, an inevitable [yet miraculous] mix of the sacred and the profane, just as Rome famously is -- I immediately thought that this flagrant contradiction of the city...should be echoed in the music."

I quibble with Salon's Andrew Hehir when he says, "Never have cynicism and disillusion seemed more intoxicating than in The Great Beauty, which is such an overwhelming visual and auditory experience that its elements of cautionary moral fable threaten to get lost amid the gorgeousness." Jep is bittersweet not world-weary. After explaining the proper way to comport oneself at a funeral, once there he violates his own rules and steals the family's thunder by weeping copiously and uncontrollably. Like Gerard Manley Hopkins's Margaret in "Spring and Fall," Jep weeps not for the unstable young man who has committed suicide or for his mother, but for himself. "It is the blight man was born for/It is Margaret you mourn for."

Indeed death hangs over The Great Beauty from the opening scenes to the end. "We're all on the brink of despair," Jep says. "All we can do is...keep each other company, joke a little." This is not as glib as it may sound on its surface. It is precisely what Samuel Beckett's Vladimir and Estragon do as they wait... and wait and wait for a Godot who will never come. "We are not saints," Didi admits, "but we have kept our appointment. How many people can boast as much?" ...to which Gogo replies, "Billions."

I quibble with Salon's Andrew Hehir when he says, "Never have cynicism and disillusion seemed more intoxicating than in The Great Beauty, which is such an overwhelming visual and auditory experience that its elements of cautionary moral fable threaten to get lost amid the gorgeousness." Jep is bittersweet not world-weary. After explaining the proper way to comport oneself at a funeral, once there he violates his own rules and steals the family's thunder by weeping copiously and uncontrollably. Like Gerard Manley Hopkins's Margaret in "Spring and Fall," Jep weeps not for the unstable young man who has committed suicide or for his mother, but for himself. "It is the blight man was born for/It is Margaret you mourn for."

Indeed death hangs over The Great Beauty from the opening scenes to the end. "We're all on the brink of despair," Jep says. "All we can do is...keep each other company, joke a little." This is not as glib as it may sound on its surface. It is precisely what Samuel Beckett's Vladimir and Estragon do as they wait... and wait and wait for a Godot who will never come. "We are not saints," Didi admits, "but we have kept our appointment. How many people can boast as much?" ...to which Gogo replies, "Billions."