Throned Upon the Awful Tree

Throned upon the awful tree,

King of grief, I watch with Thee;

Darkness veils Thine anguished face,

None its lines of woe can trace,

None can tell what pangs unknown

Hold Thee silent and alone.

Silent through those three dread hours,

Wrestling with the evil powers,

Left alone with human sin,

Gloom around Thee and within,

Till the appointed time is nigh,

Till the Lamb of God may die.

Hark, that cry that peals aloud

Upward through the whelming cloud!

Thou, the Father's only Son,

Thou, His own anointed One,

Thou dost ask him -- can it be?

"Why hast Thou forsaken Me?"

Lord, should fear and anguish roll,

Darkly o'er my sinful soul,

Thou, who once wast thus bereft

That Thine own might ne'er be left,

Teach me by that bitter cry

In the gloom to know Thee nigh.

THE HYMNS

Englishman John Ellerton -- whose long and illustrious career in the Church of England was eclipsed by his prominence as an hymnologist, editor, hymnwriter, and translator -- wrote these words in 1875 at the request of Henry Baker, Vicar of Monkland Priory Church in Herefordshire, and editor-in-chief from 1860 to 1877 of Anglican Hymns Ancient and Modern.

San Antonio Symphony violist Matthew Diekman, inspired by the hymn -- and his introduction through a colleague to the complicated, almost ceremonial process of preparing absinthe with its unique accoutrements -- set about writing a story involving the intoxicating ritual of fire and ice and a mysterious stranger who insinuates himself into a traveling party sheltering for the night under an old tree in the Texas wilderness. Diekman conceived the story as a film and enlisted his friend Matthew Dunne, composer and University of Texas at San Antonio associate professor of music, to write an original score to bring the tale to life. He then recruited a number of his San Antonio Symphony colleagues to perform it. Upon the Awful Tree is the film that grew out of that collaboration.

Musically, Diekman says, what drew him to "Throned Upon the Awful Tree" is its tonality. The hymn "is in G minor," composer Dunne explains, "but the first measure or so is really in G major. It doesn't turn minor until the second bar. It's an unexpected note when you hit that B-flat in the second bar."

The tune traces back to a Welsh folk melody entitled "Arfon," named for the southern shore of the Menai Strait in mainland Wales closest to the Island of Anglesey, and in Welsh means "facing Anglesey." "Arfon" is in G major, or G modal, with a hymn meter (not the musical meter but the pattern of syllables and stresses in the text) set to 7.7.7.7 D (the "D" indicating that the four lines of seven syllables each are doubled), a common structure in the folk tunes and hymns of English, Irish,

Scots, and Welsh immigrants that found their way into the United States with the westward expansion, being most authentically preserved in the isolated hollers of Appalachia.

The tune was published in Edward Jones's Musical and Poetical Relicks of the Welsh Bards in 1784, and itself can be traced back to a six-phrase tune in minor tonality, "Tros y Gareg" ("Over the Stone" or "Crossing the Stone"), a Celtic folk song.

"The sentiment of ['Tros y Gareg']," says Lesley Nelson-Burns, author of the comprehensive Contemplator's Folk Music Site, "is attributed to Rhys Bodychen, who led a troop of Welsh forces at the Battle of Bosworth Field where Richard III was defeated by Henry Tudor in 1485." The English lyrics were written by the 19th century linguist, translator, and playwright John Oxenford.

"Arfon" and "Tros y Gareg" have many heirs, the major tune (originally a jig) being the source for "See How Great a Flame Aspires," "Life Has Loveliness to Sell," "Jesus, Savior, Pilot Me," "Source and Sovereign, Rock and Cloud," among others. In the late 19th century in France, the tune "'Arfon' was associated with the Christmas texts 'Un nouveaux present des cieux" and "Joseph est bien marie." The minor tune provides the source for "Bread of Heaven on Thee We Feed" and "Throned Upon the Awful Tree," the melody of which was arranged in 1906 by Hugh Davies, a Welsh Methodist minister, composer, and editor of the Welsh music periodical Cerddor y Tonic Sol-ffa.

Dunne drew thematic material for the score from the opening two bars of "Throned Upon the Awful Tree" and the hymn "Day Is Dying in the West," which, Dunne says, "is really more like a jig than a hymn." The original words for the latter hymn were written by Mary A. Lathbury in 1877 (verses 1-2) and 1879 (verses 3-4). Ironically -- or not considering the consequences of Diekman's characters' lapse of judgment in the film -- Lathbury was a preeminent force in the Temperance Movement, co-authoring Woman and Temperance with Frances Elizabeth Willard in 1883. She was also an artist and book illustrator and a central figure in the Chautauqua Movement, christened the "poet laureate of Chautauqua." The tune was composed in 1877 by William Fiske Sherwin, a vocal teacher and composer of carols and hymn-tunes, and variously titled "Twilight," "Evening Praise," or "Chautauqua."

David Russell Hamrick, an academic librarian who has done extensive research on hymns for many years, feels that "Day Is Dying in the West" is among the most beautiful of hymns and unusual in that it is a call to Vespers or evening worship. Hamrick makes an interesting observation: "I have always wondered what tempo best suits 'Day Is Dying in the West.' I suspect that with a large number of people singing outdoors [as it would have been sung on Lake Chautauqua at the ecumenical evening assemblies held by the Methodist Church there], it was sung pretty slowly (maybe 60 beats per minute?) in its original context. Following my rule of thumb that a cappella congregational singing should be a little faster than accompanied singing because there is nothing filling the pauses, I have usually tried to pick the tempo up to a moderate walking pace (about 78 bpm at least). It can be sung faster, of course, but that seems to get in the way of the grandeur of the words." Having the luxury to work without the words, Dunne gradually hastens the tempo of his score as the Devil's drink increasingly overtakes the party in Diekman's film.

THE WESTERN

Diekman readily acknowledges his debt to Sergio Leone and the Spaghetti Western. In Leone's variation on the Western theme, the hero uses cunning and deceit to undermine the terror and brutality his nemeses deploy against the townspeople and against the hero himself once his double-cross is unmasked. Dunne says his composition was very much influenced by Ennio Morricone's Spaghetti Western scores. Leone and Morricone went to school together, but it was not until 1964 when Leone heard an American folk song Morricone had arranged that he enlisted his friend to write the score for A Fistful of Dollars, which would forever transform the impact a score would have in developing cinematic narrative thematic concerns.

In Westerns, the mysterious stranger is a loner, a drifter. He has undergone some trauma that functions by way of ritual initiation. The Western is not concerned with the rites of puberty, but with the rites of mystical vocation. Like the medicine man or the shaman, the stranger is able to transcend his human limitations in sacrifice to the common weal and will ultimately bring redemption (temporary though it may be) to an individual, a family, a town. The avenging angel is central to the Western genre's mythology, and he is surrounded by an olio of the good (prostitute with a heart of gold, farm family, idealistic -- Eastern -- newspaperman, The Kid, Mexican farmers); the bad (wealthy landowner, evil gunslinger, greedy bounty hunters, bankers); and the ugly, i.e. weak (milquetoast dry goods proprietor, spineless sheriff, town drunk, saloon patrons standing in for the ubiquitous mob swayed by whichever way the wind blows).

Perhaps the most powerful character in the Western, the character at its very heart, is the omniscient landscape itself -- that vast expanse of silent wilderness that is the grandeur of indifferent nature. By contrast, Diekman has trained his lens onto a claustrophobic corner of the woods, and he strips the Western's cast of stock characters down to a microcosm of traveling "innocents." A wealthy and devout rancher Wallace Hardman (J.R. Rhoades) and his daughter Sally (Morgen Johnson) have pitched camp for the night under the titular tree along with Hardman's ranch foreman (Diekman), the hand (Dave Milburn), the cook (Don McCann), and a preacher (Jack Howland). Generously played by Diekman's friends and symphony colleagues, the nonprofessional actors accomplish a subtle range of gradations of expression -- from suspicion to complicity to abandon to remorse -- without the help of words.

| Wallace Hardman (J.R. Rhodes) |

|

| Sally Hardman (Morgen Johnson) |

Discerning their initial hesitation, especially the disapproval of the Bible thumping Hardman and The Preacher, The Stranger cunningly manages to win the party's confidence and lure them in to the mysteries of the tincture contained within the bag. The gaiety of the music primes the men to abandon self-restraint, and as they imbibe, Sally, by turns nervous and coquettish, looks on. Upon the Awful Tree is not without moments of levity, but what begins as frivolity turns to transgressive miasma.

Diekman as the fiddling foreman introduces the central passage of the symphonic poem on his viola. Dunne's score allows the orchestra to sneak in little by little to gradually step up the tempo and the frenzy -- of music and camera -- as the absinthe worms its way into the revelers' veins and visions.

| The Stranger (Ryan Murphy) |

| The Preacher (Jack Howland) |

| The Fiddler (Matthew Diekman) |

Even Hardman and The Preacher are eventually sucked in to the poisoned night. When they awake, they find themselves bared by the harsh glare of the light of day that gives the lie to their superficial morality.

| ||

The Hand (David Milburn)

|

In his remarks about the film, Diekman does not mention Mark Twain's novella, posthumously published in 1916, The Mysterious Stranger, A Romance, but the obtruder of Upon the Awful Tree bears a striking resemblance to Twain's titular character who alternately refers to himself as Satan and Satan's nephew.

Among the three boys to whom Satan reveals himself is Twain's narrator, "Theodor Fischer, son of the church organist, who was also leader of the village musicians, teacher of the violin, composer, tax-collector of the commune, sexton, and in other ways a useful citizen, and respected by all" (15). On a May morning, the three playmates stretch out on the grass of a woody hilltop to smoke, but "we had been heedless and left our flint and steel behind."

Soon there came a youth strolling toward us through the trees, and he sat down and began to talk in a friendly way, just as if he knew us. But we did not answer him, for he was a stranger and we were not used to strangers and were shy of them. [....] Then I thought of the pipe, and wondered if it would be taken as kindly meant if I offered it to him. But I remembered that we had no fire, so I was sorry and disappointed. But he looked up bright and pleased, and said:Satan explains that his uncle is the only one of his clan of angels who has ever sinned, for he alone ate of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. "We others are still ignorant of sin; we are not able to commit it; we are without blemish, and shall abide in that estate always" (21). A leitmotif within Theodor's descriptions of Satan's talk -- perfect for the parallel purposes of Upon the Awful Tree -- is its musicality. He "worked his enchantments upon us again with that fatal music of his voice. [....] He

"Fire? Oh, that is easy; I will furnish it."

I was so astonished I couldn't speak; for I had not said anything. He took the pipe and blew his breath on it, and the tobacco glowed red, and spirals of blue smoke rose up. [....] He went on coaxing, in his soft, persuasive way; and when we saw that the pipe did not blow up and nothing happened, our confidence returned little by little, and presently our curiosity got to be stronger than our fear (17).

made us drunk with the joy of being with him...and of feeling the ecstasy that thrilled our veins from the touch of his hand" (23). And again, "words cannot make you understand what we felt. It was an ecstasy; and an ecstasy is a thing that will not go into words; it feels like music, and one cannot tell about music so that another person can get the feeling of it" (28).

|

| Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens, 1835-1910) |

The Mysterious Stranger revolves around Satan's argument (which is Twain's) that humanity's downfall derives from its Moral Sense. Having eaten the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, we know what is right, yet every useful citizen respected by all inevitably, knowingly chooses to do wrong for so trivial a reason as to save face in the eyes of equally unworthy others. The story proceeds episodically from one admonitory plot twist to another, beginning when Satan takes

Theodor into the torture chamber of the village jail, which makes Theodor feel "faint and sick."

Theodor into the torture chamber of the village jail, which makes Theodor feel "faint and sick."

I said it was a brutal thing.Satan's cautionary vignettes heighten for Theodor scenes close to home as they play out in juxtaposition to "a history of the progress of the human race -- its development of that product which it calls civilization" (94).

"No, it was a human thing" [, says Satan]. "You should not insult the brutes by such a misuse of that word; they have not deserved it.... It is your paltry race -- always lying and always claiming virtues which it hasn't got, always denying them to the higher animals, which alone possess them. No brute ever does a cruel thing -- that is the monopoly of those with the Moral Sense" (48).

The Mysterious Stranger is among the darker works from a writer enshrined as America's great humorist, and it depicts life as a nightmarish dream. Indeed, when the boys introduce Satan to their friends, he asks that they introduce him as Philip Traum: "You see, [Theodor explains to the reader,] 'Traum' is German for 'Dream'" (62). James Joyce's Stephen Dedalus will make the succinct observation that "History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake," an eternal stream of violence against the disenfranchised, the violence justified by absolving the persecutors of blame, which, as Twain's time-traveling Satan demonstrates again and again, is indeed the perpetual history of both church and state.

"In Upon the Awful Tree," Diekman says, "the time-traveling Mysterious Stranger/Satan is timeless in his appearance, yet there are subtle hints in his attire and his gestures that are throwbacks -- and throw-forwards -- that the viewer will understand but the characters won't. The Stranger's bag of tricks draws from the past, present, and future," Diekman explains, "just as the biblical struggle between good and evil starts at the beginning of humankind and is eternal."

THE ABSINTHE

In 1899, the English Decadent poet Ernest Dowson wrote "Absinthia Taetra" ("abominable absinthe"):

Ballet relies on the language of music and the gesture of dance to convey narrative, and musical compositions have been composed for centuries around narrative stories. Fred Everett Maus introduces his (highly recommended) paper "Music As Narrative," published in the Indiana Theory Review, arguing that "For many listeners, some instrumental music, especially in the tradition of Haydn and Mozart through Brahms, invites comparison to drama or narrative" (1).

Discussing Schumann's Second Symphony he notes, "Musical events can be regarded as characters, or as gestures, assertions, responses, resolutions, goal-directed motions, references, and so on. Once they are so regarded, it is easy to regard successions of musical events as forming something like a story, in which these characters and actions go together to form something like a plot" (6).

Maus's analysis of the last movement of Beethoven's Piano Sonata, Gp. 14, No. 1 concludes, "This description treats the events in the Rondo as a series of actions, repeated attempts to reach a satisfactory state of affairs that requires no further action. The attempts are defeated, repeatedly, because satisfaction involves a return of the opening key and opening thematic material, but the thematic material throws the pitch materials off balance. The attempts are not exactly those of the

composer or performer, but seem to be best understood as behavior in a fictional world created through the music. The Rondo does not encode a story about something completely nonmusical, in the manner of program music. Rather, the goals, actions, and problems of the story are musical ones, and they share only rather general descriptions (for instance, 'trying to return to a position of stability') with everyday actions. Though it would be possible to add specifications of agents to the story, it is not necessary to do so, and in fact it seems best to give an account...that leaves the determination of character vague" (13-14).

Though it is a film, Upon the Awful Tree places its dominant reliance on the vaguer, less literal musical composition. Indeed in describing the film, Diekman refers to it as "The little movie with the million dollar soundtrack." Budgetary constraints put writer, director, producer, cinematographer, editor, production/art/set/costume designer Diekman in a do-the-best-with-what-you've-got quandary. He shot with a DSLR camera in video mode, so it is not surprising that production values are somewhat compromised. He recruited his colleagues for the orchestra, and as professional symphony musicians they turn in a superb performance. As nonprofessional actors (and generous friends indeed), they rose to the thespian challenge as well.

Under the Awful Tree premiered in San Antonio on June 2, and interestingly, Ukrainian director Myroslav Slaboshpytskiy's The Tribe opened June 19 in New York. Though it has not made its way to San Antonio yet, I mention it because it shares a number of aspects with Diekman's film: it features a nonprofessional cast; it explores a microcosm -- a boarding school -- governed by the teens' violent code of transgression; and, because all of the characters are deaf, it is performed entirely in sign language with no subtitles or intertitles. In the case of The Tribe, there is also no orchestral soundtrack or incidental music. Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian noted that he "couldn't help remembering the quotation attributed to Nietzsche about dancers being thought insane by those who can't hear the music."

"In Upon the Awful Tree," Diekman says, "the time-traveling Mysterious Stranger/Satan is timeless in his appearance, yet there are subtle hints in his attire and his gestures that are throwbacks -- and throw-forwards -- that the viewer will understand but the characters won't. The Stranger's bag of tricks draws from the past, present, and future," Diekman explains, "just as the biblical struggle between good and evil starts at the beginning of humankind and is eternal."

THE ABSINTHE

Satan recounts for Theodor and his mates a litany of the progress of the human race -- from Cain bludgeoning Abel to death "followed by a long series of unknown wars, murders, and massacres" (95). The Flood provides humanity with a second chance. Instead the peoples of the earth carry on: from Sodom and Gomorrah; to Lot and his daughters; to the Hebraic wars; to Jael; to the Egyptian, Greek, and Roman wars, and Caesar's invasion of Britain; down to Christianity and Civilization "leaving famine and death and desolation in their wake..." (96). "And always," Theodor laments, "we had wars, and more wars, and still other wars..." (96).

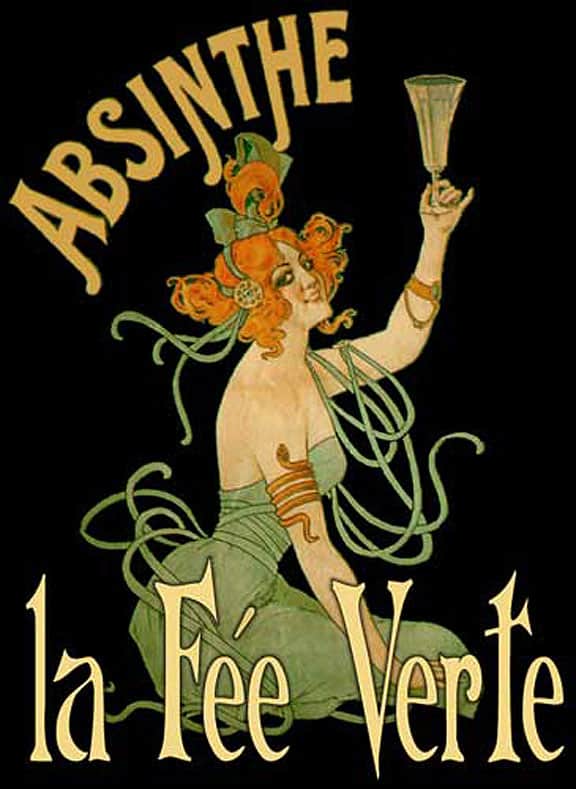

The only rational reaction to the eternal human condition is madness, oblivion, or the slumber of death. The Stranger in Upon the Awful Tree offers the oblivion of la fée verte (the green fairy), the anise-flavored spirit made of wormwood, anise, fennel, and herbs long believed to possess hallucinogenic properties.

The oldest and purest method of preparing absinthe, the French Method, is to pour the green spirit into the properly measured bulbous well at the bottom of a Pontarlier glass and then to rest a silver absinthe cuillere -- a special slotted spoon -- across the rim. A sugar cube is placed on the cuillere and the absinthe diluted by slowly dripping iced water over the sugar from a carafe, which causes the absinthe's less soluble essences -- wormwood, anise, and fennel -- to dissolve and cloud. This allows the aromatic subtleties that remain muted in the neat spirit to blossom or bloom. The resulting opalescent liquid is called the louche.

In 1899, the English Decadent poet Ernest Dowson wrote "Absinthia Taetra" ("abominable absinthe"):

Green changed to white, emerald to an opal: nothing was changed.

The man let the water trickle gently into his glass, and as the green clouded, a mist fell from his mind.

Then he drank opaline.

Memories and terrors beset him. The past tore after him like a panther and through the blackness of the present he saw the luminous tiger eyes of the things to be.

But he drank opaline.

And that obscure night of the soul, and the valley of humiliation, through which he stumbled were forgotten. He saw blue vistas of undiscovered countries, high prospects and a quiet, caressing sea. The past shed its perfume over him, to-day held his hand as it were a little child, and to-morrow shone like a white star: nothing was changed.

He drank opaline.

The man had known the obscure night of the soul, and lay even now in the valley of humiliation; and the tiger menace of the things to be was red in the skies. But for a little while he had forgotten.

Green changed to white, emerald to opal: nothing was changed.

The Bohemian Method used in Upon the Awful Tree involves first soaking the sugar cube in absinthe, then setting it aflame before dropping it into the absinthe-filled Pontarlier glass. The spirit ignites and is finished by tossing an ice cube in to douse the flames, resulting in a stronger drink. This is a modern technique not employed at the turn of the 20th century, but Twain stretches the plausibility of his schoolboys smoking as early as 1590. Phantasmagoria can happily admit anachronism and allow for Satan's fiery breath upon Twain's tobacco and Diekman's absinthe.

THE WORDLESSNESS

The degree of prominence the role music would play in Upon the Awful Tree evolved throughout the film's conception. "When I started writing the screenplay," Diekman says, "I thought I'd see how far I could get without anybody saying anything. And if somebody needs to say something, I thought, I'll let them. But I wrote and wrote and wrote, and I got to 'the end' and nobody said anything."

Wordless narrative is nothing new. Pantomimus was the name for a masked dancer in Ancient Greece, and unscripted mummer plays were a staple of Medieval European folk performance.

The degree of prominence the role music would play in Upon the Awful Tree evolved throughout the film's conception. "When I started writing the screenplay," Diekman says, "I thought I'd see how far I could get without anybody saying anything. And if somebody needs to say something, I thought, I'll let them. But I wrote and wrote and wrote, and I got to 'the end' and nobody said anything."

Wordless narrative is nothing new. Pantomimus was the name for a masked dancer in Ancient Greece, and unscripted mummer plays were a staple of Medieval European folk performance.

The masque was central to 16th and 17th century court entertainments in Europe. From dumbshows at London's Globe Theater to the new dance drama that emerged in early 17th century Japan that would become kabuki to the play-within-the-play in Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot, pantomime has endured.

Upon the Awful Tree plays like an extended surrealist interlude that Alejandro Jodorowsky, the father of the Acid Western, would appreciate. Jodorowsky studied mime in Paris with Étienne Decroux and joined Marcel Marceau's troupe. He worked as a clown before founding Teatro Mimico in Mexico City in 1947. His 1970 El Topo follows a silent sharp-shooter on a violent quest for enlightenment through a mystical Western landscape.

|

| Alejandro Jodorowsky's 1970 El Topo |

Screen actors of the silent era utilized the mime's exaggerated gestures and facial expressions, but their dialog was relayed to audiences in intertitles (or title cards) between action shots. "I don't consider [Upon the Awful Tree] a silent film," Diekman insists. "I consider it a dialogue-free film." Indeed, unlike silent films, Upon the Awful Tree incorporates only a smattering of intertitles, interspersed among its opening shots, by way of setting the stage, and then abandons them altogether. "Some of my favorite scenes in my favorite movies are the ones in which people stop talking and take action to advance the plot," Diekman continues. "I wanted to see if I could expand that kind of non-verbal storytelling to an entire film narrative. It worked."

In print, the closest relatives to Diekman's experiment grew out of German Expressionism and were initiated with Frans Masereel's 1918 wordless novel 25 Images of a Man's Passion.

|

| Last four panels of Frans Masereel's 1918 25 Images of a Man's Passion |

The first and most prominent practitioner of the medium in the United States was Lynd Ward, who, beginning in 1929, produced a series of six "wordless novels in woodcuts," as he called them. I inherited a first edition of the second novel in the series, Mad Man's Drum, a story of the sins of the fathers that Art Spiegelman, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel Maus: A Survivor's Tale and editor of The Library of America's 2010 boxed-set edition of Ward's collected novels, describes as "a multigenerational saga worthy of Faulkner [that] traces the legacy of violence haunting a family whose stock in trade is human souls."

|

| Lynd Ward's Mad Man's Drum |

|

| Lynd Ward's Mad Man's Drum |

Ward was a friend of my grandfather Charles W. Richards. In addition to the trade edition in 1930, a special edition of 309 signed copies was published of which 299 were for sale. Ward gave my grandfather #171 of the signed edition. In undergraduate school, a friend and I pored through it page by page one summer and wrote out the narrative, a document I have often wished I would run across in my files, though I seriously doubt is extant.

Ballet relies on the language of music and the gesture of dance to convey narrative, and musical compositions have been composed for centuries around narrative stories. Fred Everett Maus introduces his (highly recommended) paper "Music As Narrative," published in the Indiana Theory Review, arguing that "For many listeners, some instrumental music, especially in the tradition of Haydn and Mozart through Brahms, invites comparison to drama or narrative" (1).

Discussing Schumann's Second Symphony he notes, "Musical events can be regarded as characters, or as gestures, assertions, responses, resolutions, goal-directed motions, references, and so on. Once they are so regarded, it is easy to regard successions of musical events as forming something like a story, in which these characters and actions go together to form something like a plot" (6).

Maus's analysis of the last movement of Beethoven's Piano Sonata, Gp. 14, No. 1 concludes, "This description treats the events in the Rondo as a series of actions, repeated attempts to reach a satisfactory state of affairs that requires no further action. The attempts are defeated, repeatedly, because satisfaction involves a return of the opening key and opening thematic material, but the thematic material throws the pitch materials off balance. The attempts are not exactly those of the

composer or performer, but seem to be best understood as behavior in a fictional world created through the music. The Rondo does not encode a story about something completely nonmusical, in the manner of program music. Rather, the goals, actions, and problems of the story are musical ones, and they share only rather general descriptions (for instance, 'trying to return to a position of stability') with everyday actions. Though it would be possible to add specifications of agents to the story, it is not necessary to do so, and in fact it seems best to give an account...that leaves the determination of character vague" (13-14).

Though it is a film, Upon the Awful Tree places its dominant reliance on the vaguer, less literal musical composition. Indeed in describing the film, Diekman refers to it as "The little movie with the million dollar soundtrack." Budgetary constraints put writer, director, producer, cinematographer, editor, production/art/set/costume designer Diekman in a do-the-best-with-what-you've-got quandary. He shot with a DSLR camera in video mode, so it is not surprising that production values are somewhat compromised. He recruited his colleagues for the orchestra, and as professional symphony musicians they turn in a superb performance. As nonprofessional actors (and generous friends indeed), they rose to the thespian challenge as well.

Under the Awful Tree premiered in San Antonio on June 2, and interestingly, Ukrainian director Myroslav Slaboshpytskiy's The Tribe opened June 19 in New York. Though it has not made its way to San Antonio yet, I mention it because it shares a number of aspects with Diekman's film: it features a nonprofessional cast; it explores a microcosm -- a boarding school -- governed by the teens' violent code of transgression; and, because all of the characters are deaf, it is performed entirely in sign language with no subtitles or intertitles. In the case of The Tribe, there is also no orchestral soundtrack or incidental music. Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian noted that he "couldn't help remembering the quotation attributed to Nietzsche about dancers being thought insane by those who can't hear the music."

|

| Myroslav Slaboshpytskiy's The Tribe |

|

| Myroslav Slaboshpytskiy's The Tribe |

The Tribe also shares, from all accounts, Twain's bleak view of the human condition: were we to remove the blinkers Twain's Satan calls our Moral Sense, we would realize we are irredeemable. Among the few intertitles that punctuate the opening shots of Upon the Awful Tree is a quote from Oscar Wilde that informs the arc of the action that will follow:

"After the first glass of absinthe you see things as you wish they were. After the second you see them as they are not. Finally you see things as they really are, and that is the most horrible thing in the world.""Throned Upon the Awful Tree" depicts the solitary Christ upon the rood:

silent and alone.

Silent through those three dread hours,Christ speaks only to implore of God, "Why hast Thou forsaken Me?" The speaker of the hymn in turn asks Christ to "Teach me by that bitter cry/In the gloom to know Thee nigh." If that final line is supposed to inspire hope, it falls distressingly short, in my opinion. Not a day, nay an hour, goes by that negates Satan's measure of man, yet I continue to put my faith in the redemptive power of art. Art does a peculiar thing. It simultaneously transports us out of and into the human condition, and unlike absinthe, the experience of art is clear-headed with the potential to make us rise above that condition: the hymn and the jig, the sacred and the profane, the existential paradox of the human double helix.

Wrestling with the evil powers,

Left alone with human sin,

Gloom around Thee and within....

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The majority of Matthew Diekman's and Matthew Dunne's remarks quoted in this essay are taken from Nathan Cone's interview for Texas Public Radio KSTX 89.1 FM. Cone, Director of Cultural and Community Engagement at KSTX, organizes the TPR Cinema Tuesday series in San Antonio, where Upon the Awful Tree premiered on June 2, 2015 at the Santikos Bijou theater.

Quotations from Mark Twain's The Mysterious Stranger come from Prometheus Books' 1995 Literary Classics edition.

Quotations from Mark Twain's The Mysterious Stranger come from Prometheus Books' 1995 Literary Classics edition.