"You want to torture me, but I can simply kill myself first. Do you want revenge, or do you want the truth?" Oh Dae-su's captor Lee Woo-jin, Park Chan-wook's 2003 Oldboy

Revenge is, as they say, as old as the hills. My paternal grandmother Kempf was named Nancy Jett Cockrell, and both the Cockrells and the Jetts figured prominently in the notorious Breathitt County Kentucky Feuds of the latter half of the 19th century, more infamous and far bloodier than anything between the more storied Hatfields and McCoys.

The December 9, 1878 New York Times printed a special dispatch that began, "Affairs in Breathitt County are in a far worse condition than reported heretofore. The only two newspaper men who have made their way into that county arrived in Louisville to-day, and describe a most deplorable state of society."

"The Beginning of the Strife," the article explains, began "During [the Civil War when] they were permitted to do pretty much as they wished, and got so used to killing their enemies on the slightest pretext that they could not or would not leave off the habit when they were called upon to do so."

The reporters seek to discover the initiating incident for the feud, but the stories differ radically: the theft of a watermelon; a group of marauders' quarrel over the division of their spoils of war; a little boy who "set afloat a slanderous story about a Miss Cockerill;" etc. Whatever sparked the feud, the reporters were there seven years later to investigate its escalation over a tangle of events: a disputed County Judge election won "by a majority of eight votes," a subsequent contested Common School Commissioner's election, and the judge's enforcement of Jason Little's -- "one of the famous Little brothers" who murdered his wife to marry another woman -- court appearance.

"All [who came to the court] were armed to the teeth, and most of them were under the influence of whiskey. Instead of stacking their arms [in front of the courthouse] as they had agreed to do, they went about the streets, some with two or three revolvers strapped to their belts, and some with Sharp and Ballard rifles." That was on Monday. On Tuesday, "Men crazed with whiskey charged through the streets, afoot and on horseback, brandishing their revolvers and carbines, and threatening to kill every person who came in their path. Women and children ran through the yards and gardens screaming with fear, and some of them fainted. Blood flowed freely."

"On Wednesday morning Judge Randall, without waiting to adjourn court, jumped upon his horse and took an unceremonious departure."

A second dispatch concludes, "One thing is certain -- the men of both factions...are camping out in the brush, with plenty of arms and munitions of war with them. Hidden among the mountains, they are so secluded from the rest of mankind that they seem to forget there is an outside world, and dream that the only object in life is to fight out to the death, if necessary, the petty disputes that arise among themselves."

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In Renaissance England, not surprisingly considering the political climate of the times, the revenge tragedy gained enormous

popularity. Thomas Kyd is credited with establishing the genre with The Spanish Tragedy, written some time between 1582

and 1592, but Shakespeare's Hamlet and the Scottish play are the

most theatrically well-known and oft-performed. After Shakespeare's plays, John Webster's The White Devil (1612) and The Duchess of Malfi (1612-1613) are staged more often today than any other Jacobean dramas, though J. R. Mulryne argues that "Webster mockingly repudiates the revenge tragedy form in The White Devil and The Duchess of Malfi, [where he] intentionally creates a world of 'moral and emotional anarchy.'"

The genre is generally traced to three sources. Most commonly, the Roman Stoic Seneca, who wrote in the first century CE, is credited with creating the original revenge tragedies, though certainly the theme is a staple of mythology and religion. Seneca's works were first translated into English in 1559, and in the ensuing 20 years, the plays were widely circulated, especially Medea, Agamemnon, and Thyestes, from which Shakespeare borrowed plot elements for Titus Andronicus -- all tales of blood revenge. Some critics argue that the Italian nouvelle, which often revolves around feuding families -- the premise upon which Shakespeare sets Romeo and Juliet -- figured as another influence, and some that medieval contemptus mundo ("contempt of the world") is reflected in the single-mindedness, preoccupation with death, and dismissal of the quotidian for a mystical stoicism that are so much a part of the avenger's character.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

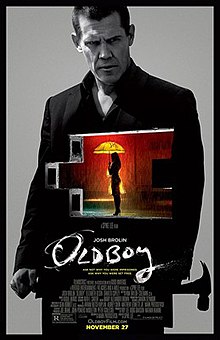

Spike Lee's Oldboy is a remake of Park Chan-wook's 2003 film, the second in Park's Vengeance Trilogy (bracketed by the 2002 Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance and the 2005 Lady Vengeance) and based on a manga by Garon Tsuchiya and Nobuaki Minegishi. Like the original, it unfolds in concentric circles of revelation as to who is the avenged and who the avenger.

The title "Oldboy" itself gives the protagonist's tale (Oh Dae-su's in Park and Joe Doucette's in Lee -- a diminutive of Joe Doe?) an aura of Everyman -- the universal id, the primal lust for payback, blood reckoning, an eye for an eye. It is ancient, a permanent aspect of the human condition. Much as we might like to think we have evolved beyond base desires for vengeance, culturally at least, the demand for retribution is as fundamental today as it has ever been, to judge from our ten years and going engagement in Iraq and Afghanistan (not to mention all of the dirty wars the U.S. is engaged in across the globe).

In an excellent 2009 overview of the movies of the first decade of the 21st century, A.O. Scott considers the resurgence of vengeance as a cinematic theme. He argues that with the turn of the century, we got a mixed bag of fantasy, superheroes, "midbudget Oscar bait, Will Ferrell and Sacha Baron Cohen...and the Transformers movies, along with everything else."

"How else to make sense of the prevalence of revenge as a motive, a problem and a source of catharsis? It was hardly a new topic — payback has been the common currency of cowboys and samurai, rogue cops and righteous criminals, for a very long time — but in noncomic genres vengeance could seem like the only game in town. Sometimes the urge to repay blood with blood was treated with skepticism or at least with a sense of moral complication, as in Mystic River or In the Bedroom or The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada. But the tone for mainstream commercial entertainment was set early on, when Gladiator won the first Best Picture Oscar of the new decade. And nearly every hero thereafter, from Aragorn and Harry Potter to Spider-Man and even the newly young Mr. Spock and the newly sad James Bond, was caught up in a Manichaean struggle defined by an endless cycle of vendetta and reprisal.

"This was even true of Jesus, whose travails in Mel Gibson's Passion of the Christ played like the first act of a revenge drama, the one in which the hero is humbled as pre-emptive justification for whatever fury he comes back to unleash at the end. The violence in that film, which seemed shocking at the time, now seems fairly typical of a mainstream popular cinema saturated with images of bodily torment.

"And also, perhaps, of a taste for primal, antimodern scenarios of action and reaction, in which the nuances of politics and the deliberative institutions of justice are treated with suspicion, even contempt. ....

"There is something profoundly regressive in the vision of a civilization stripped down to an essentially violent core...."

Joe Doucette (convincingly played by Josh Brolin) is a drunk and a bully, a victim of the world just barely holding on to his advertising accounts. His wife has taken their infant daughter and moved out, we can only assume out of self defense. This particular day is the daughter's birthday, but instead of taking her present to her, Doucette embarks on a tanked-up night of self pity. He awakes imprisoned in what appears to be a seedy hotel room. The news on the TV reveals why he is condemned, but it does not help him establish the identity of his jailer, who will keep him there for 25 years (10 years longer than Park's protagonist). As the years pass, the TV is also a source of information, in the form of talk shows, about his daughter. (There is much more to all of this than what I say here, but I don't want to give anything away.)

Viewed as a two-act play, Doucette's confinement constitutes Act I, and follows the arc of an individual from wallowing fatalism to averted suicide to resolve. He religiously follows the self-help programs offered up from his TV and becomes a disciplined body builder and practitioner of yoga and meditation, all in the service of finding his captor and avenging himself.

Act II opens with Doucette's mysterious release as he emerges from a trunk in a vacant field. His difficulty maneuvering through a world that has in practical ways become foreign to him is alleviated by a social worker he encounters when his path intersects with a mobile drug rehab clinic. When she discovers his story, she becomes his aide in tracking the identity of his captor, a process that will bring him face to face, first with his distant, then his recent, past.

For the most part, Lee's Oldboy is faithful to Park's, not only in the outline of the plot, but in visual tone and narrative pacing. Writing for Roger Ebert Movies, Matt Zoller Seitz makes the following astute observation:

"The big problem with Lee's Oldboy is that for all its dark confidence, it doesn't reimagine the original boldly enough. This isn't like Martin Scorsese's Cape Fear, David Cronenberg's The Fly or Jonathan Demme's The Manchurian Candidate....all of which drastically rethought their inspirations. Lee's Oldboy, in contrast, is more like Point of No Return, the American remake of La Femme Nikita. It's so close to its predecessor in so many ways that I can't see much reason for it to exist, except to give xenophobic viewers an experience similar to the original, but minus the subtitled Korean and the octopus-eating scene—and with a more ostentatiously cartoonish bad guy, and lot more monologuing to explain the convoluted plot."

Scott provided the answer to the question of why Spike Lee finds the re-telling of Park's tale as relevant as it was 10 years ago. In the ensuing decade, the violence we were shocked by "now seems fairly typical of a mainstream popular cinema," as Scott says. Our "taste for primal, antimodern scenarios of action and reaction, in which the nuances of politics and the deliberative institutions of justice are treated with suspicion, even contempt," has not been slaked. Rather it has left us hungry for more.

We are in the habit of employing the phrase "as the tale unfolds," and Doucette's tale is one of pealing back the folds of many veils. What I have outlined are the broadest brush strokes of the story. Much as I am tempted, I will not produce a spoiler at this point.

Oldboy is a revenge tragedy, yes, but it also has much of the three blind men and the elephant in it. As the convolutions of the story unravel and recoil, we realize that each character understands events through the lens of his own ego. The story might also serve as a morality tale, suggesting to us that our judgment of the world is not necessarily accurate, that we might be surprised to discover that the opinions we construct around other peoples are not at all the same as the image they have of themselves as a people, and their judgments about us might equally surprise. This is the primary reason that Lee's softening of the final scenes does such a disservice. The story demands the hyperbole and intensity that Park invests in it. It is a tragedy, after all. For all the gore and stylization of both films, in the end Park's protagonist undergoes a profound transformation of the soul that is lacking in Lee's telling. Maybe he had to tone it down to appease the studio, but it detracts from the catharsis the narrative is ultimately there to serve.

Shakespeare has had his share of feature film productions. There has been no end of film adaptations of Hamlet, and I am going to ignore Romeo and Juliet here. The

Scottish play has been brought to the screen seven times: in silents from J. Stuart Blackton in 1908 and John Emerson in 1916, Orson

Welles's in 1948, Roman Polanski's in 1971, Arthur Allan Seidelman's in 1981, Jeremy Freeston and Brian Blessed's in 1997, and Geoffrey Wright's in 2006, as well as a half dozen adaptations.

Marion Cotillard and Michael Fassbender are slated to star in an upcoming version directed by Australian Justin Kurzel.

Othello has one silent production, Dimitri Buchowetzki's in 1922, and four later screen versions: David MacKane's in 1946, Orson Welles's in 1952, Sergei Yutkevich's in 1955, and Oliver Parker in 1995, as well as a half dozen adaptations.

By contrast, King Lear has seen only two significant film versions: Grigori Kozintsev's in 1971 and Peter Brook's in 1971, but it has been adapted by Akiri Kurosawa in the 1985 Ran, Jean-Luc Godard in 1987, Jocylyn Moorhouse in the 1997 A Thousand Acres, and the plot has influenced numerous family dramas. Julius Caesar has seen only three film incarnations: David Bradley's in 1950, Joseph L. Mankiewicz's in 1953, and Stuart Burge's in 1970. Charlton Heston directed Antony and Cleopatra in 1972, Ralph Fiennes Coriolanus in 2012, and Julie Taymor Titus Andronicus in the 1999 Titus.

Othello has one silent production, Dimitri Buchowetzki's in 1922, and four later screen versions: David MacKane's in 1946, Orson Welles's in 1952, Sergei Yutkevich's in 1955, and Oliver Parker in 1995, as well as a half dozen adaptations.

By contrast, King Lear has seen only two significant film versions: Grigori Kozintsev's in 1971 and Peter Brook's in 1971, but it has been adapted by Akiri Kurosawa in the 1985 Ran, Jean-Luc Godard in 1987, Jocylyn Moorhouse in the 1997 A Thousand Acres, and the plot has influenced numerous family dramas. Julius Caesar has seen only three film incarnations: David Bradley's in 1950, Joseph L. Mankiewicz's in 1953, and Stuart Burge's in 1970. Charlton Heston directed Antony and Cleopatra in 1972, Ralph Fiennes Coriolanus in 2012, and Julie Taymor Titus Andronicus in the 1999 Titus.

Other notable film versions of classic revenge plays are Derek Jarman's 1991 Edward II based on the 1593 play by Christopher Marlowe, Alex Cox's 2002 Revengers Tragedy based on the 1606 play attributed to Thomas Middleton, and Marcus Thompson's 1998 Middleton's Changling based on Thomas Middleton and William Rowley's 1662 The Changling.

Some of the more significant revenge narratives adapted for the

screen are:

Ingmar Bergman's 1960 The Virgin Spring from the 13th-century Swedish ballad "Töres döttrar i Wänge" ("Töre's daughters in Vänge")

Ingmar Bergman's 1960 The Virgin Spring from the 13th-century Swedish ballad "Töres döttrar i Wänge" ("Töre's daughters in Vänge")

J. Lee Thompson's 1962 and Martin Scorsese's 1991 Cape

Fear from John D. McDonald's 1957 novel The Executioners

John Boorman's 1967 Point Blank from the 1962 novel The Hunter by Donald E. Westlake writing as Richard Stark

John Boorman's 1967 Point Blank from the 1962 novel The Hunter by Donald E. Westlake writing as Richard Stark

Henry Hathaway's 1969 and the Coen Brothers' 2010 True Grit from

Charles Portis's 1968 novel

Mike Hodges's 1971 Get Carter from Ted Lewis's 1969 novel Jack's

Return Home

Robert M. Young's 1986 Extremities from William Mastrosimone's 1982

play

Barry Levinson's 1996 Sleepers from Lorenzo Carcaterra's 1995

novel

Christopher Nolan's 2000 Memento from his younger brother's short

story "Memento Mori"

Todd Field's 2001 masterpiece In the Bedroom from the 1979 short story "Killings" by Andre Dubus

Martin Scorsese's 2002 Gangs of New York inspired by Herbert

Asbury's historical account

Tetsuya Nakashima's 2010 Confessions from Kanae Minato's 2008

novel

...and some notable original screenplays are:

George Miller's 1979 Mad Max

John Woo's 1989 The Killer

Peter Greenaway's 1989 The Cook, the Thief, His Wife, and Her

Lover

Clint Eastwood's 1992 Unforgiven

Gasper Noé's 2002 non-linear narrative

Irréversible

Mike Hodges 2003 I'll Sleep When I'm Dead

Lars von Trier's 2003 Dogville, which was to be the first in his Land of Opportunities or US Trilogy, followed in 2005 by Manderlay, but the

final segment, Washington, was never realized

Quentin Tarantino's 2003 Kill Bill: Vol. 1 and 2004 Kill Bill: Vol.

2 also initially conceived as a trilogy, though Vol. 3, originally planned for

a 2014 release, probably will not be realized

I enjoyed the scholarly study of revenge stories a propos of Spike Lee's new release, but am totally fascinated by your own family history. Wow!

ReplyDelete