|

Des glaneuses, 1857, Jean-François Millet

Musée d'Orsay, Paris |

Just as portraiture is the original mode of photography, so documentary is the original mode of moving pictures. A movie camera records an event in motion: a trolley barreling down a street, an athlete tumbling through space. The earliest documentaries, due to late-19th century technical limitations, could capture only a few moments in time, but as technological improvements freed recording duration, newsreels became a staple of the first couple decades of the 20th century. The one I always think of as serving the dual purposes of recording an important event for posterity and screening an event as news, is the solemn funeral cortège of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in 1914, after his assassination in Sarajevo, the spark that ignited World War I.

|

| Funeral cortège of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, July 4, 1914 |

Subsequent filmmakers took issue with Flaherty's artifice, giving rise to avant-garde movements in the 1920s that professed to a higher documentary truth. Arguably, the most notable of these was the Russian director Dziga Vertov, whose Kino-Pravda group -- literally "Film Truth" -- produced a newsreel series, sometimes with a hidden camera, that focused on everyday experiences and, for the most part, eschewed reenactments. Vertov's 1929, 68-minute Man with a Movie Camera was a visual manifesto of his political and aesthetic cinematic philosophy: to present "life as it is," "life caught unawares," yet he did so, with the valiant efforts of his wife Elizaveta Svilova in the critical role of film editor, through some of the most arresting effects ever committed to film.

With the economic disruptions of the late '20s and early '30s through the war-time trauma of the '40s, fascistic and leftist ideologues alike employed the documentary mode for propagandistic purposes, e.g., Leni Riefenstahl's 1935 Triumph of the Will for the Third Reich and Frank Capra's 1942-1944 series Why We Fight for the United States government.

|

| Poster for Dziga Vertov's 1929 Man with a Movie Camera |

Technical advances -- light-weight, quiet handheld cameras and portable synchronized sound capabilities -- encouraged post-World War II filmmakers to approach documentary filmmaking in new ways. In the 1950s, French anthropologist Jean Rouch developed a film philosophy of Cinéma Vérité, which sought to impose an ethic on the line between fictionalization and documentary in a style now called ethnofiction (enthnographic docufiction). The difference between Rouch's approach and what Flaherty had done in Nanook was that Flaherty's dramatization served to romanticize (melodramaticize, if you will) his subjects whereas Rouch's dramatizations served the loftier aim of political indictment. Rouch's 1958 Moi, un noir is considered a seminal work of ethnographic storytelling and is hailed as one of the signal influences on the French New Wave movement, whose auteur directors were emerging simultaneously: François Truffaut's The 400 Blows was released in 1959 and Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless in 1960. Rouch insisted, in a way that Curtis had not acknowledged, that the very presence of the filmmaker interferes with the documentary record he is attempting to capture -- cameraman as de facto agent provocateur, so to speak.

In North America, Direct Cinema grew out of Rouch's influence and his concerns regarding reality in relationship to the inevitable manipulations of the filmmaker. Yet, whereas Cinéma Vérité often involved staging, even provoking subjects, Direct Cinema's aim was for subject and viewing audience alike to have no awareness of the camera's presence, and one way to lessen the sense of the intrusive filmmaker was to eliminate the voice-over narrator.

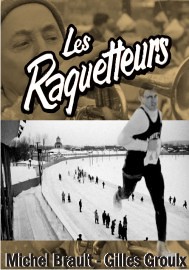

Direct Cinema was born in 1958 when the National Film Board of Canada released Québécois Michel Brault and Giles Groulx's Les raquetteurs, which documents a convention of snowshoers in Sherbrooke, Quebec. Les raquetteurs and Groulx's 1961 Golden Gloves, about three Montreal boxers in training, had a direct impact on the British-born Richard Leacock, D.A. Pennebaker, and Albert and David Maysles in the United States. Leacock's first documentary, Toby and the Tall Corn, aired in 1954 on CBS's Omnibus, where Leacock met Robert Drew, an editor at Life magazine who specialized in the candid still picture essay. Drew was interested in a less verbal approach to television reportage, without interviews. Together Leacock and Drew interfaced a tape recorder and a mobile quartz camera with the design of an Accutron watch (which uses a 360 hertz tuning fork instead of a balance wheel as the timekeeping mechanism), thereby enabling them to synchronize the two machines without cables.

In "Richard Leacock: Bearing Witness," Brian Winston, who has written extensively on documentary and ethics, says, "Leacock was the catalyst for the development of the m odern documentary, liberating the camera from the tripod and abandoning the tyranny of the perfectly stable, perfectly lit shot – as well as the straitjacket of ‘voice of god’ commentary."

Drew formed Drew Associates, which produced Primary in 1960 (shot by Leacock and Albert Maysles and edited by Pennebaker) "the first film in which the sync-sound motion picture camera was able to move freely with characters throughout a breaking story," John F. Kennedy's and Hubert Humphrey's respective Democratic primary campaigns in Wisconsin. Seven years later, in 1967 (the same year he shot the footage for Monterey Pop), Pennebaker's monumental portrait of Bob Dylan, Dont Look Back (created from footage shot in 1965), would be released.

Albert Maysles was a psychology professor at Boston University and head of a research project at Massachusetts General Hospital. In 1955, CBS gave him a camera with which to record a research project abroad. The resulting film was the drably titled Psychiatry in Russia. His younger brother David also studied psychology at Boston University but began working as a Hollywood production assistant in the mid-1950s. By 1957, the brothers had become a team, shooting documentaries behind the Iron Curtain. In 1960, they joined the burgeoning Drew Associates. The Maysles are best known for Salesman (1969), Gimme Shelter (1970), and Grey Gardens (1975), though their combined individual filmographies, along with their collaborations, reveal a staggeringly impressive oeuvre. Among my favorites is Running Fence (with Charlotte Zwerin), which chronicles the challenges Christo and Jeanne-Claude faced to install the 1976 environmental work in northern California.

|

| Christo and Jeanne-Claude's 1976 Running Fence Sonoma and Marin Counties, California |

Fourteen years after Resnais's Night and Fog, Marcel Ophüls' The Sorrow and the Pity was released in 1969. The film chronicles the collaboration between the Vichy government and Nazi Germany, and though The Sorrow and the Pity contains historical footage, its investigation relies on numerous contemporary interviews with those involved: a Jewish diplomat, a German officer, French collaborators, and resistance fighters among them. Organized into two parts, the first centers on an extended interview with Pierre Mendès France, a Jew who had been Secretary of State for Finance under France's Popular Front government and was arrested by the subsequent Vichy government. The second part centers on Christian de la Mazière, an aristocrat, journalist, and member of the Charlemagne Division of the Waffen SS. Though Ophüls did not associate himself with any particular documentary philosophy, he used "a characteristically sober interview style to resolve disparate experiences into a persuasive argument"* with The Sorrow and the Pity and documentaries like The Memory of Justice and Hôtel Terminus: The Life and Times of Klaus Barbi.

When most people think of the word "documentary," they think of the observational mode, the approach that Leacock, Drew, Pennebaker, and the Maysles played a pivotal role in establishing -- and the approach that Errol Morris would play a pivotal role in transforming. With his groundbreaking investigation into the unjust conviction and imprisonment of Randall Dale Adams for the murder of a Dallas police officer, Morris's award-winning documentary The Thin Blue Line made an indelible impact on subsequent documentarians. First, Morris again introduced reenactments but did so based on meticulous examinations of witness statements and testimony. Second, he developed a recording style that grew out of happenstance. On the day of the final interview with David Harris, the man (the film argues) who shot the officer, Morris's camera broke down. He resorted to a run-of-the-mill recorder for the interview, and for the finished cut of the film, shot a tape recorder from various angles from which he created a montage over which the voices from the tape were superimposed. From that serendipitous misfortune, Morris developed a technique he first employed in Fast Cheap and Out of Control (1997) that his wife later termed "interrotron": Morris behind a curtain staring into a camera that in turn feeds into a teleprompter-like device through which the interviewee looks directly at the camera.

In his commentary on his documentary on Stephen Hawking's book A Brief History of Time, Morris makes a critical distinction: "You don't judge a documentary film on whether it tells the truth. You judge it on whether it attempts to find the truth and makes you think about what the relationship between the movie and the truth may be. Truth is never given to us on a platter."

An intimately personal approach to the documentary has emerged with the turn of the 21st century, and just as Agnès Varda is credited as the mother of the French New Wave, we might credit her as the architect of this subjective, autobiographical approach to documentary with The Gleaners and I and The Beaches of Agnès.

One of the best recent explorations of this approach is Sarah Polley's 2013 documentary, Stories We Tell, in which Polley tries to tease out the "truth" of her mother's intimacies. "When [Polley] found her answer, and talked to her father and siblings about it," Mary Jo Murphy writes in the New York Times, "she became fascinated with how each of them was 'telling the story and embellishing the story and making the story their own.' The act of telling the story, [Polley] said, 'was changing the story itself.'"

Polley knows that most of us, “We do get stuff wrong and everything is kind of subjective. That’s part of who we are as human beings. We tell stories as well as we can but generally kind of sloppily even when we’re trying our hardest.”

AGNÈS VARDA AND THE FRENCH NEW WAVE

Agnès Varda has always been interested in documentary, narrative realism, social commentary, and feminist concerns. Her name is legendary as one of the pioneers of the French New Wave, and her career is remarkable in the stature of her achievement not only as the only woman in a '60s movement dominated by men, but as one of its inspirations, along with cinematic modernist forerunners Robert Bresson, Jean Cocteau, and Alexandre Astruc.

|

| The young Agnès Varda, c. 1960s |

The Cahiers du Cinéma group included Claude Chabrol, Godard, Éric Rohmer, and Truffaut. Rive Gauche, or Left Bank Cinema, directors held a more traditional view of cinema as another facet of the literary arts. Though they tended to be older than their Right Bank counterparts, they too were interested in technical experimentation. The Rive Gauche group included Chris Marker, Resnais, and Varda, as well as Jean-Pierre Melville, and Alain Robbe-Grillet. Both groups identified with the political left, and those political concerns emerge in the subjects their films explore. The Cahiers du Cinéma magazine became progressively political throughout the '60s until, by 1970, it reflected a decidedly Marxist ideology. It continues to be published today but with a less political agenda.

THE GLEANERS AND I

Varda's 2000 film The Gleaners and I (literally, Les glaneurs et la glaneuse, meaning the gleaners and the female gleaner) is a singular documentary: part social commentary, part travelogue, part history and wide ranging art historical project. part memento mori. The Criterion Collection says Varda describes her style as cinécriture, or writing on film, "and it can be seen in formally audacious fictions like Le bonheur and Vagabond as well as more ragged and revealing documentaries like The Gleaners and I and The Beaches of Agnès."

My first encounter with Varda was the compelling 1985 Vagabond or Sans toit ni loi -- literally "without roof nor law," a play on the French idiom "sans foi ni loi," "without faith nor law." The film follows a peripatetic young woman, destitute and homeless, wandering the French countryside. The film opens on her frozen corpse, then flashes back to her last days. Varda approaches her desperate subject not as a picaresque literary figure but as a real young woman, alone and adrift in an indifferent landscape, sans any element of satire.

Subsequent to Vagabond, I have sought Varda out on DVD, most recently The Gleaners and I, Varda's first foray into digital film. She traversed the French countryside from September 1999 through May 2000 with a handheld camera. "These new small cameras," she says, "they are digital, fantastic. Their effects are stroboscopic, narcissistic, and even hyper-realistic."

The documentary that came out of that journey is personal in the extreme and like any meaningful art, an exploration of the universal concerns of the human condition: We all eat, we all lay waste the bounty that is ours, we all make human connections, we all hoard material objects just as we collect and preserve in memory our sense of who we are, and, of course, we all die.

Grain

As her entrée into France's breadbasket, Varda opens a lexicon, the seminal French Larousse Dictionary, where we learn the verb "glaner" (to glean) means not simply "to gather," but to gather after the harvest. The definition is accompanied by etchings after Jean-François Millet's 1857 Des glaneuses (The Gleaners), the original of which hangs in the Musée d'Orsay in Paris. Varda locates the practice of gleaning historically, first, as an activity that by definition is the gathering of what has been left behind and second, as labor relegated to women and carried out among them collectively. Within this context, Varda brings her inquiry forward to our own times and mores concerning bounty and waste, indulgence and want. "In the towns of today as in the fields of yesterday, gleaners still humbly stoop to glean. But men have now joined with women in gleaning. What strikes me," Varda says of contemporary gleaners, "is that each gleans on his own. Whereas in paintings they were always in clusters, rarely alone."

An 1877 painting by Jules Breton at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Arras, is famous not only because it shows a lone figure but also because, unlike the stooping postures in other representations, Breton's gleaner stands nobly upright, her sheaves not in her apron but borne upon her shoulder. Varda visits the painting, and herself has her portrait photographed standing proudly upright with her sheaves, like Breton's La Glaneuse, across her shoulder. "There is another woman gleaning in this film, that's me (se moi)," and indeed, Varda sets out to glean the gleaners of every stripe in our own time, steering her crew south to the Beauce region between the Seine and the Loire, known as the granary of France.

Potatoes

Beauce is renowned for its wheat, but "the harvest being over we'll focus on potato gleaning instead." A potato farmer tells Varda, "Some people are quite pleased when the machine malfunctions." We rely on the efficiency of contemporary harvesting equipment, but in our dependence, we sacrifice intimacy with the land. Worse, we have developed certain (some might say peculiar, even perverse) expectations about what our food should look like. A grocer explains that "In supermarkets, the firm [potatoes] are sold in containers of 5 1/2 to 11 pounds, and these have to be a specific caliber, of a specific size. So we dump anything bigger." Twenty-five tons of viable potatoes are abandoned each harvest just because, by arbitrary commercial standards, the produce is considered "misshapen." Varda is particularly taken with those "deformed" in heart shapes, which she collects to use in a lighthearted montage. Because so many potatoes are dumped, "The practice of gleaning has reappeared," a farmer explains. In a single day, volunteers for a charity salvage almost 700 pounds of perfectly good potatoes. "Same with cauliflower," another man tells Varda, "fruit and vegetables in other regions, but here it's potato country and we take what we can find."

Her crew travels to a gypsy caravan where Varda asks if they know they can legally gather dumped potatoes, and it turns out they do not. Nearby homeless people dwelling in tiny camper trailers not only glean from fields but from dumpsters behind supermarkets filled to brimming with food cleared from grocery shelves. "We're not afraid to get our hands dirty," one explains. "You can wash hands."

Varda stops to visit Édouard Loubet, "the youngest French chef to have earned two stars in the Michelin guide." Loubet owns Le Moulin de Lourmarin and Le Galinier de Lourmarin in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, but he gleans herbs and fruit for his restaurants because he wants fresh ingredients rather than refrigerated produce from Italy. Varda, by including the master chef Loubet in her film about detritus, juxtaposes the homeless with an elitist cultural attitude toward food.

Grapes

From Provence, Varda makes her way to the great terroir of Burgundy, where she stops to contemplate Rogier van der Weyden's Beaune Altarpiece (c. 1445-1450) whose subject is the Last Judgment. The Chancellor of the Duchy of Burgundy commissioned the Flemish artist to create the altarpiece in 1443. Comprised of fifteen paintings on nine panels, six of which, being hinged shutters, are painted on both sides, the altarpiece depicts the realms of the divine, the earthly, and the infernal.

Varda focuses on the latter. Whereas a traditional rendering of the Last Judgment would depict demons and fiends tormenting the accursed, van der Weyden has painted tormented souls whose anguish is rendered only through their contorted expressions and postures. Varda speculates on the punishments meted out for gluttony before turning her gaze to notice that no gleaners are in sight, even though the grape harvest has just ended. A Burgundian cafe owner explains that gleaning differs from picking: "You pick the fruit that hangs but you glean things that sprout." One gleans grain; one picks olives and almonds and figs.

Vintners and farmers have made picking in Burgundy illegal. One vintner explains that "If you want your wine to be ranked as a vintage, the yearly production is limited. That means you can only produce a certain quota per plot." The rest is left to rot, vintners wary that pickers will harm their vines. Like vineyard owners, fig growers purposely throw fruit deemed unworthy to the ground to molder, ensuring enforcement of the injunction against picking -- even after harvest.

Modern harvesting equipment leaves abundant sprouted crop behind -- cabbages and tomatoes -- and though Burgundians have managed to criminalize picking, French penal code allows for gleaning with impunity "from sunup until sundown" as long as it occurs after the harvest, explains Mr. Dessaud, Varda's "lawyer in the fields." Varda finds an old law commentary with an edict from November 2, 1554, "which says just the same as today. It allows the poor, the wretched, the deprived to enter the fields once harvesting is over. Old documents talk of the poor, the destitute, but how are we to consider those who want for nothing and glean just for fun?" Varda asks Dessaud. "If they glean for fun, it's because they have a need for fun," he reasons.

In the countryside of the Jura region, Varda encounters the Nenon family, in the hills near Apt, who "present a special case of picking. The vineyard they found was wholly abandoned." In this region, after November 1, they are free to take the harvest to save it from wild boars and birds.

In the fruit groves of Arles, the foreman of Cape Farm tells Varda, "We often allow gleaners to come in after our pickers, provided they remain 10 yards behind." Another fruit grower explains, "We can't prevent people providing themselves with apples once we have finished harvesting. So we proclaim an official gleaning period, we take [car] registrations down, if it's a moped, we ask for a Xerox of the owner's ID...."" "Isn't it a bit over-regulated?" Varda asks. "Once people are registered, they can take 400 pounds, I don't mind, even if it's a whole lot," he says by way of explanation. Gleaners can even enter greenhouses once the harvest is collected.

Oysters

Though the island of Noirmoutier is known for its causeway and for the delicate, almost extinct La Bonnotte potato, with its distinctive salty, earthy flavor derived from its cultivation in the algae and seaweed laden soil, Varda visits to talk to local oyster gleaners who scour the beaches after rough storms and very low tides have dislodged oysters from their beds and washed them ashore. She's told they "go in as soon as the storm has abated." Oyster gleaning is legal within certain parameters, though the gleaners almost purposefully seem to have a vague notion of the actual terms of the law. Is one to stay 10 yards away from the poles marking the beds? 15? 25? Is the maximum number of oysters per person 7 pounds? 11? "Seven pounds of clams and 11 pounds of oysters, something like that," says one. "Three dozen [oysters] per person, but surely they take more than that," says another.

Art

Throughout her travels, Varda interviews artists who incorporate the discarded into their work. Having considered gleaning and picking, she explores loading up, "retrieving heavy objects people get rid of," an artist who makes images from salvaged material explains. He defines himself equally as a painter and a retriever. "What's good about these objects is that they've already had a life, and they're still very much alive. All you have to do is give them a second chance."

Passing an abandoned factory on one side and a shop with the sign "Finds," Varda notes, " 'Curios' is common, but 'Finds' is more inviting." Lo and behold, inside she finds a painting of gleaners, a charming amateur picture that combines "both the humble stooping of Millet's Glaneuses and the proud posture of Breton's Gleaner. "The painter," Varda surmises, "had an old dictionary at hand. Honest, this is no movie trick. We really did find these Glaneuses purely by chance. The painting had beckoned us because it belonged here in this film."

Varda loads up her serendipitous treasure and heads to the Ideal Palace of Bodan Litnianski. Litnianski immigrated from Ukraine to France around 1930 at the age of 17. He worked as a bricklayer and mason, then served France in World War II. After being released from a prisoner of war camp, Litnianski returned to France and settled in a house in Viry-Noureuil, near Chauny, in the Aisne department of northern France. Once he had decorated the exterior of the house with all manner of objets trouvés, he "started building totem towers made of scraps he found in dumps and brought back in his trailer hooked to his moped." "It's solid stuff, you know," Litnianski assures Varda, "very solid. I'm a brickmason. I like dolls, they're my system. Dolls are characters."

Varda visits the French assemblage artist Louis Pons who describes the detritus from which he creates his work as "my dictionary, useless things. People think it's a cluster of junk. I see it as a cluster of possibilities. Each object gives a direction, each is a line, picked up here and there, indeed gleaned, and which become my paintings. The aim of art is to tidy one's inner and exterior worlds," Pons says. "I make sentences from things."

Trash

Varda turns to Mrs. Espie, her "lawyer in the streets," to understand the French statute on abandoned objects. "The law on gleaning doesn't apply to these objects. 'Res derelictee' are ownerless things, since the owner's intention has been clearly expressed: they have deliberately abandoned them. ...[T]his property can't be stolen since it has no owner." People salvage appliances from the streets to repair or repurpose, and some glean TVs for copper wire. Varda investigates the Waste Ground artists of Villeneuve Sur Lot, a collective that creates domestic-themed tableaux resembling large-scale dollhouses from discarded refrigerators.

In Prades, Varda interviews a man only identified by his green rubber boots. He tells her, "I have a job, a salary, a social security number. Salvaging is a matter of ethics for me, because I find it utterly unacceptable to see all this waste on the streets." Back in her own Montparnasse neighborhood in Paris, Varda finally introduces herself to a man she has repeatedly noticed in the wee hours after her street market closes down. He eats as he gleans, like a ruminant grazing through the vendors' leavings. Interviewing him over a number of weeks, Varda learns he is a former teaching assistant with a Master's in biology. For whatever reason, he now sells street papers and maps in front of the train station. For eight years he has lived in a shelter many miles away where fully half of the mostly immigrant residents are illiterate. For six years, for two hours every evening, he has been teaching them to read and write in a basement classroom he has arranged for his tutees' convenience. "I'm not part of the school system, I don't get paid for it." "Meeting that man is what impressed me the most," Varda says of her cinematic journey.

Coda

"The other high point is quite different in kind." Varda talked the Musée Municipal, Villefranche-sur-Saône into bringing out a long-neglected painting by Pierre-Edmond Hédouin, which Varda had only seen reproduced in black and white. Gleaners at Chambaudoin, fleeing the storm was first exhibited in 1857, the same year as Millet's Des glaneuses. The curator and her assistant carry the large canvas outside as a storm gathers, the gusts and thunder audible on the dialogue track, while on the canvas Hédouin's gleaners run from a darkening sky, sheaves over shoulders and above their heads, their skirts pressed against their bodies by the wind. "To see them in broad daylight, with stormy gusts lashing against the canvas, was true delight."

In the course of her travels, Varda has made a stop at the Domaine de la Folie, Côte Chalonnaise, a 16th century estate that has been in the Noël-Bouton family for three centuries and is considered a leading Burgundy wine producer in Rully. "The domaine is unique in the Rully [appellation contrôlée] in that it is...northernmost...and its 32 acres of vines are the highest in elevation. Moreover, all but one of these vineyards are monopoles (a fact that leaps out in the context of Burgundy). Lastly, unlike the main body of vineyards in the central part of Rully to the south, this northern end of the Montagne de la Folie sits on the same vein of limestone as the commune of Puligny-Montrachet, just over three miles away."

Jérôme Noël-Bouton explains that his grandmother was the daughter of Étienne-Jules Marey. At the time that Noël-Bouton's grandmother, Marey's daughter, married a Bouton, the estate had fallen out of Bouton hands. Marey bought it and returned it to the Bouton family.

But Varda has not come for wine. Marey was not a vintner but a physiologist and the inventor of chronophotography, a process by which several phases of movement are recorded onto a single photographic plate. Noël-Bouton shows Varda the tower Marey built to house his still camera equipment. "He set up wires," Noël-Bouton explains, "and waited. Animals or birds went past triggering the camera. That's the hut," he says, pointing to another structure, "from which, with his chronophotographic rifle, he broke down the flight of birds." Marey published La Machine animale (Animal Mechanism) in 1873. Eadweard Muybridge published his Photographic Investigation in 1897 in an effort to prove Marey's contention that all four hooves of a galloping horse, for however brief a moment, are together off the ground.

"He was a visionary," Varda says of Marey. "He analyzed movement before Muybridge and the Lumières. He is the ancestor of all movie makers."

Finally, throughout her film, Varda superimposes a second narrative, for, after all, her title is The Gleaners ... and I. She made the film when she was 72. Aptly then, in a documentary exploration of what comes after the farms' and vineyards' harvests, after the groceries' expiration dates, after use and wear have consigned material objects to dustbins, it is only fitting that Varda punctuate her rumination with a parallel narrative that gleans her own physique for traces of mortality. Like the chiming of a clock, at intervals Varda trains her inquiry onto herself. "My hair and my hands keep telling me that the end is near."

"And then my hand up close,.. this is my project: to film with one hand my other hand. To enter into the horror of it. I find it extraordinary. ...I am an animal I don't know."

"One night when the bulky refuse is thrown out, I drove around with François [Wetheimer]," a friend who scored Varda's 1977 One Sings, the Other Doesn't and who likes rummaging. Varda reports he looked at an empty clock and turned it down. "I picked it up and took it home. A clock without hands is my kind of thing. You don't see time passing," Varda explains, as her visage, like a pendulum making a sweep in one direction only, moves across the tableaux into which she has situated the clock.

The compactness and portability of her digital camera have allowed Varda to look and see and film in new ways. "I'll walk my small camera among the colored cabbages and film other vegetables which catch my eye. On this kind of gleaning, of images, impressions, there is no legislation, and gleaning is defined figuratively as a mental activity. To glean facts, acts and deeds, to glean information. And for forgetful me, it's what I have gleaned that tells me where I've been."

*Armstrong, Richard, et al. The Rough Guide to Film: An A-Z of Directors and Their Movies. London: Penguin, 2007. 399-400.

The Gleaners and I is available from Netflix DVD and Instant Play, Amazon. It can be purchased from Zeitgeist Films,

My first encounter with Varda was the compelling 1985 Vagabond or Sans toit ni loi -- literally "without roof nor law," a play on the French idiom "sans foi ni loi," "without faith nor law." The film follows a peripatetic young woman, destitute and homeless, wandering the French countryside. The film opens on her frozen corpse, then flashes back to her last days. Varda approaches her desperate subject not as a picaresque literary figure but as a real young woman, alone and adrift in an indifferent landscape, sans any element of satire.

Subsequent to Vagabond, I have sought Varda out on DVD, most recently The Gleaners and I, Varda's first foray into digital film. She traversed the French countryside from September 1999 through May 2000 with a handheld camera. "These new small cameras," she says, "they are digital, fantastic. Their effects are stroboscopic, narcissistic, and even hyper-realistic."

The documentary that came out of that journey is personal in the extreme and like any meaningful art, an exploration of the universal concerns of the human condition: We all eat, we all lay waste the bounty that is ours, we all make human connections, we all hoard material objects just as we collect and preserve in memory our sense of who we are, and, of course, we all die.

Grain

As her entrée into France's breadbasket, Varda opens a lexicon, the seminal French Larousse Dictionary, where we learn the verb "glaner" (to glean) means not simply "to gather," but to gather after the harvest. The definition is accompanied by etchings after Jean-François Millet's 1857 Des glaneuses (The Gleaners), the original of which hangs in the Musée d'Orsay in Paris. Varda locates the practice of gleaning historically, first, as an activity that by definition is the gathering of what has been left behind and second, as labor relegated to women and carried out among them collectively. Within this context, Varda brings her inquiry forward to our own times and mores concerning bounty and waste, indulgence and want. "In the towns of today as in the fields of yesterday, gleaners still humbly stoop to glean. But men have now joined with women in gleaning. What strikes me," Varda says of contemporary gleaners, "is that each gleans on his own. Whereas in paintings they were always in clusters, rarely alone."

|

Des glaneuses, 1857, Jean-François Millet

Musée d'Orsay, Paris |

| La Glaneuse, 1877, Jules Breton Musée des Beaux-Arts, Arras |

Beauce is renowned for its wheat, but "the harvest being over we'll focus on potato gleaning instead." A potato farmer tells Varda, "Some people are quite pleased when the machine malfunctions." We rely on the efficiency of contemporary harvesting equipment, but in our dependence, we sacrifice intimacy with the land. Worse, we have developed certain (some might say peculiar, even perverse) expectations about what our food should look like. A grocer explains that "In supermarkets, the firm [potatoes] are sold in containers of 5 1/2 to 11 pounds, and these have to be a specific caliber, of a specific size. So we dump anything bigger." Twenty-five tons of viable potatoes are abandoned each harvest just because, by arbitrary commercial standards, the produce is considered "misshapen." Varda is particularly taken with those "deformed" in heart shapes, which she collects to use in a lighthearted montage. Because so many potatoes are dumped, "The practice of gleaning has reappeared," a farmer explains. In a single day, volunteers for a charity salvage almost 700 pounds of perfectly good potatoes. "Same with cauliflower," another man tells Varda, "fruit and vegetables in other regions, but here it's potato country and we take what we can find."

Her crew travels to a gypsy caravan where Varda asks if they know they can legally gather dumped potatoes, and it turns out they do not. Nearby homeless people dwelling in tiny camper trailers not only glean from fields but from dumpsters behind supermarkets filled to brimming with food cleared from grocery shelves. "We're not afraid to get our hands dirty," one explains. "You can wash hands."

Varda stops to visit Édouard Loubet, "the youngest French chef to have earned two stars in the Michelin guide." Loubet owns Le Moulin de Lourmarin and Le Galinier de Lourmarin in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, but he gleans herbs and fruit for his restaurants because he wants fresh ingredients rather than refrigerated produce from Italy. Varda, by including the master chef Loubet in her film about detritus, juxtaposes the homeless with an elitist cultural attitude toward food.

Grapes

From Provence, Varda makes her way to the great terroir of Burgundy, where she stops to contemplate Rogier van der Weyden's Beaune Altarpiece (c. 1445-1450) whose subject is the Last Judgment. The Chancellor of the Duchy of Burgundy commissioned the Flemish artist to create the altarpiece in 1443. Comprised of fifteen paintings on nine panels, six of which, being hinged shutters, are painted on both sides, the altarpiece depicts the realms of the divine, the earthly, and the infernal.

|

| Rogier van der Weyden's Beaune Altarpiece, c. 1445-1450 |

|

| Rogier van der Weyden's Beaune Altarpiece, c. 1445-1450 Detail |

Modern harvesting equipment leaves abundant sprouted crop behind -- cabbages and tomatoes -- and though Burgundians have managed to criminalize picking, French penal code allows for gleaning with impunity "from sunup until sundown" as long as it occurs after the harvest, explains Mr. Dessaud, Varda's "lawyer in the fields." Varda finds an old law commentary with an edict from November 2, 1554, "which says just the same as today. It allows the poor, the wretched, the deprived to enter the fields once harvesting is over. Old documents talk of the poor, the destitute, but how are we to consider those who want for nothing and glean just for fun?" Varda asks Dessaud. "If they glean for fun, it's because they have a need for fun," he reasons.

In the countryside of the Jura region, Varda encounters the Nenon family, in the hills near Apt, who "present a special case of picking. The vineyard they found was wholly abandoned." In this region, after November 1, they are free to take the harvest to save it from wild boars and birds.

In the fruit groves of Arles, the foreman of Cape Farm tells Varda, "We often allow gleaners to come in after our pickers, provided they remain 10 yards behind." Another fruit grower explains, "We can't prevent people providing themselves with apples once we have finished harvesting. So we proclaim an official gleaning period, we take [car] registrations down, if it's a moped, we ask for a Xerox of the owner's ID...."" "Isn't it a bit over-regulated?" Varda asks. "Once people are registered, they can take 400 pounds, I don't mind, even if it's a whole lot," he says by way of explanation. Gleaners can even enter greenhouses once the harvest is collected.

Oysters

Though the island of Noirmoutier is known for its causeway and for the delicate, almost extinct La Bonnotte potato, with its distinctive salty, earthy flavor derived from its cultivation in the algae and seaweed laden soil, Varda visits to talk to local oyster gleaners who scour the beaches after rough storms and very low tides have dislodged oysters from their beds and washed them ashore. She's told they "go in as soon as the storm has abated." Oyster gleaning is legal within certain parameters, though the gleaners almost purposefully seem to have a vague notion of the actual terms of the law. Is one to stay 10 yards away from the poles marking the beds? 15? 25? Is the maximum number of oysters per person 7 pounds? 11? "Seven pounds of clams and 11 pounds of oysters, something like that," says one. "Three dozen [oysters] per person, but surely they take more than that," says another.

Art

Throughout her travels, Varda interviews artists who incorporate the discarded into their work. Having considered gleaning and picking, she explores loading up, "retrieving heavy objects people get rid of," an artist who makes images from salvaged material explains. He defines himself equally as a painter and a retriever. "What's good about these objects is that they've already had a life, and they're still very much alive. All you have to do is give them a second chance."

Passing an abandoned factory on one side and a shop with the sign "Finds," Varda notes, " 'Curios' is common, but 'Finds' is more inviting." Lo and behold, inside she finds a painting of gleaners, a charming amateur picture that combines "both the humble stooping of Millet's Glaneuses and the proud posture of Breton's Gleaner. "The painter," Varda surmises, "had an old dictionary at hand. Honest, this is no movie trick. We really did find these Glaneuses purely by chance. The painting had beckoned us because it belonged here in this film."

Varda loads up her serendipitous treasure and heads to the Ideal Palace of Bodan Litnianski. Litnianski immigrated from Ukraine to France around 1930 at the age of 17. He worked as a bricklayer and mason, then served France in World War II. After being released from a prisoner of war camp, Litnianski returned to France and settled in a house in Viry-Noureuil, near Chauny, in the Aisne department of northern France. Once he had decorated the exterior of the house with all manner of objets trouvés, he "started building totem towers made of scraps he found in dumps and brought back in his trailer hooked to his moped." "It's solid stuff, you know," Litnianski assures Varda, "very solid. I'm a brickmason. I like dolls, they're my system. Dolls are characters."

|

| The Ideal Palace of Bodan Litnianski, c. 2000, Viry-Noureuil |

|

| Ma ville, 1970, Louis Pons |

Varda turns to Mrs. Espie, her "lawyer in the streets," to understand the French statute on abandoned objects. "The law on gleaning doesn't apply to these objects. 'Res derelictee' are ownerless things, since the owner's intention has been clearly expressed: they have deliberately abandoned them. ...[T]his property can't be stolen since it has no owner." People salvage appliances from the streets to repair or repurpose, and some glean TVs for copper wire. Varda investigates the Waste Ground artists of Villeneuve Sur Lot, a collective that creates domestic-themed tableaux resembling large-scale dollhouses from discarded refrigerators.

In Prades, Varda interviews a man only identified by his green rubber boots. He tells her, "I have a job, a salary, a social security number. Salvaging is a matter of ethics for me, because I find it utterly unacceptable to see all this waste on the streets." Back in her own Montparnasse neighborhood in Paris, Varda finally introduces herself to a man she has repeatedly noticed in the wee hours after her street market closes down. He eats as he gleans, like a ruminant grazing through the vendors' leavings. Interviewing him over a number of weeks, Varda learns he is a former teaching assistant with a Master's in biology. For whatever reason, he now sells street papers and maps in front of the train station. For eight years he has lived in a shelter many miles away where fully half of the mostly immigrant residents are illiterate. For six years, for two hours every evening, he has been teaching them to read and write in a basement classroom he has arranged for his tutees' convenience. "I'm not part of the school system, I don't get paid for it." "Meeting that man is what impressed me the most," Varda says of her cinematic journey.

Coda

"The other high point is quite different in kind." Varda talked the Musée Municipal, Villefranche-sur-Saône into bringing out a long-neglected painting by Pierre-Edmond Hédouin, which Varda had only seen reproduced in black and white. Gleaners at Chambaudoin, fleeing the storm was first exhibited in 1857, the same year as Millet's Des glaneuses. The curator and her assistant carry the large canvas outside as a storm gathers, the gusts and thunder audible on the dialogue track, while on the canvas Hédouin's gleaners run from a darkening sky, sheaves over shoulders and above their heads, their skirts pressed against their bodies by the wind. "To see them in broad daylight, with stormy gusts lashing against the canvas, was true delight."

|

| Glaneuses à Chambaudoin/Gleaners Fleeing Before the Storm, 1857, Edmond Hédouin Musée Municipal, Villefranche-sur-Saône |

Jérôme Noël-Bouton explains that his grandmother was the daughter of Étienne-Jules Marey. At the time that Noël-Bouton's grandmother, Marey's daughter, married a Bouton, the estate had fallen out of Bouton hands. Marey bought it and returned it to the Bouton family.

But Varda has not come for wine. Marey was not a vintner but a physiologist and the inventor of chronophotography, a process by which several phases of movement are recorded onto a single photographic plate. Noël-Bouton shows Varda the tower Marey built to house his still camera equipment. "He set up wires," Noël-Bouton explains, "and waited. Animals or birds went past triggering the camera. That's the hut," he says, pointing to another structure, "from which, with his chronophotographic rifle, he broke down the flight of birds." Marey published La Machine animale (Animal Mechanism) in 1873. Eadweard Muybridge published his Photographic Investigation in 1897 in an effort to prove Marey's contention that all four hooves of a galloping horse, for however brief a moment, are together off the ground.

"He was a visionary," Varda says of Marey. "He analyzed movement before Muybridge and the Lumières. He is the ancestor of all movie makers."

|

| "Marey's experimental pictures and film bits," Varda says, "...are pure visual delight." |

"And then my hand up close,.. this is my project: to film with one hand my other hand. To enter into the horror of it. I find it extraordinary. ...I am an animal I don't know."

"One night when the bulky refuse is thrown out, I drove around with François [Wetheimer]," a friend who scored Varda's 1977 One Sings, the Other Doesn't and who likes rummaging. Varda reports he looked at an empty clock and turned it down. "I picked it up and took it home. A clock without hands is my kind of thing. You don't see time passing," Varda explains, as her visage, like a pendulum making a sweep in one direction only, moves across the tableaux into which she has situated the clock.

The compactness and portability of her digital camera have allowed Varda to look and see and film in new ways. "I'll walk my small camera among the colored cabbages and film other vegetables which catch my eye. On this kind of gleaning, of images, impressions, there is no legislation, and gleaning is defined figuratively as a mental activity. To glean facts, acts and deeds, to glean information. And for forgetful me, it's what I have gleaned that tells me where I've been."

|

| Agnès Varda visiting the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Arras |

*Armstrong, Richard, et al. The Rough Guide to Film: An A-Z of Directors and Their Movies. London: Penguin, 2007. 399-400.

The Gleaners and I is available from Netflix DVD and Instant Play, Amazon. It can be purchased from Zeitgeist Films,

Medina, Jennifer. "Getting Ugly Produce Onto Tables So It Stays Out of Trash." New York Times 23 November 2015. Online.

.jpg)

We found your weblog is very handy for us. When you keep going this perfect work I’ll come back to your site!

ReplyDeletescheibenfolie für auto