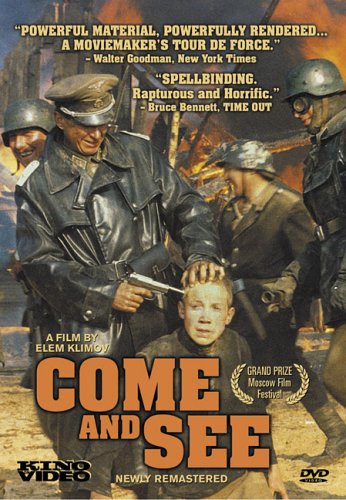

Let's take The Color Purple (1985) as an arbitrary starting point. Good god, man – it takes more than a bucket, a mop and a good cinematographer to turn a hovel into a bucolic cottage set amidst billowing fields of sun-dappled wildflowers. Then there's the requisite, manipulative John Williams score. Midway through, as I heaved yet another sob, sinuses swollen, I was ready to strangle the both of them for so artificially wrenching emotion out of the audience. Schindler's List (1993)? What's with that fleeting little girl in the red coat who keeps showing up in the frame? Is she a metaphor? If so, a metaphor for what? Then in 1998, the inaugural film in what we might call "Spielberg's Tom Hanks Era," Saving Private Ryan: Quit telling me it is the most realistic depiction of war ever captured on film, because anyone who makes such a claim has not bothered to see Bernhard Wicki's 1959 The Bridge, Elem Klimov's 1985 Come and See, or Patrick Sheane Duncan's 1989 84 Charlie MoPic.

In 2011, I subjected myself to both Spielberg holiday movies. The Adventures of Tintin starts out remarkably true to the wonderful Hergé creation, but instead of using one Tintin story, Spielberg proceeds to mash up three (“The Crab With the Golden Claws” [1941], “The Secret of the Unicorn” [1943] and “Red Rackham’s Treasure” [also 1943]). Tintin is a child journalist who, attended by his Wire Fox Terrier Snowy, is forever finding himself called to distant shores to solve inscrutable mysteries. Spielberg makes no attempt to mine the sharp geopolitical parody that was the raison d'etre for many of the Tintin stories. Instead, Hergé's intrepid character and the graphic charm of the ligne claire (clean line) style he pioneered are soon mauled when, no longer able to contain himself, Spielberg lets loose an endless animated CGI orgy. The youngsters in my audience began to crawl out of their seats and into the aisles to tune Spielberg out altogether and lose themselves in their own imaginations. Usually scornful of restless audiences, I sympathized while trying to stifle one sigh of annoyance after another. Writing in London's The Guardian, literary critic Nicholas Lezard rued, "Coming out of the...film..., I found myself, for a few seconds, too stunned and sickened to speak; for I had been obliged to watch two hours of literally senseless violence being perpetrated on something I loved dearly. In fact, the sense of violation was so strong that it felt as though I had witnessed a rape."

Then came War Horse right on Tintin's heels, with yet another John Williams score and good actors playing caricatures for Hallmark-Hall-of-Fame-tear-jerker effect. The horse is about the only player in the film Spielberg was unable to turn into a stock character. His sentimental nostalgia for overwrought Hollywood epics is almost as gratuitous as his addiction to CGI.

Daniel-Day Lewis, David Strathairn, James Spader, Hal Holbrook, Tommy Lee Jones, John Hawkes... distracted, I started to wonder which big-name actors would NOT appear in Lincoln (2012). I was also annoyed that virtually every African American in the film was expected to look supplicatingly at all the nice white people. (In all fairness, for once I liked John Williams' score.) I was gratified, therefore, when, after the torrent of laudatory reviews, I ran across a critical opinion in The New York Times editorial pages (not the Movies Section, mind you) by Kate Masur, associate professor of history at Northwestern and the author of An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle Over Equality in Washington, D.C. Lincoln is determined, Masur argues, "to see emancipation as a gift from white people to black people, not as a social transformation in which African-Americans themselves played a role."

|

| Almost 180,000 African Americans fought in the Civil War, constituting about one-tenth of the manpower of the Union Army. Source: William A. Gladstone. United States Colored Troops, 1863-1867 (1996) |

FBI Agent Hoffman (Scott Shepherd): We need to know what the Russian was telling you. Don't go all boy scout on me. We don't have a rule book here...

Donovan: You're Agent Hoffman, yeah? You're German extraction. My name's Donovan. Irish. Both sides. Mother and father. I'm Irish, you're German. But what makes us both Americans? Just one thing. One, only one. The rule book. We call it the Constitution. We agree to the rules, and that's what makes us Americans. It's all that makes us Americans so don't tell me there's no rule book and don't nod at me like that, you son of a bitch. [I don't think the violins soared, but this little speech certainly gives the cue.]

|

| Center: Tom Hanks as James B. Donovan and Amy Ryan as his wife Mary in Bridge of Spies |

Spielberg has clearly modeled Donovan's family on Father Knows Best. The son (Noah Schnapp) is all Leave It to Beaver earnestness; the daughters (Jillian Lebling and Eve Hewson) suitably vulnerable; and Donovan, a jovial and tolerant dad à la Ozzie, is protective of his indulgent and devoted wife Mary à la Harriet. Mary (Amy Ryan) dons the same string of pearls June Cleaver, Donna Reed and Margaret Anderson were never without. She wears eyeglasses in one scene only, presumably to establish that the prop manager was able to come up with period spectacles.

Bridge of Spies is designed to tap our nostalgia – at least the heartstrings of those of us who are boomers – while at the same time suggesting how bad the Soviet "evil empire" was. Yet it never penetrates its veneer to convey the ubiquity of the fear the threat of imminent nuclear annihilation provoked (despite a scene of tearful youngsters as their teacher shows them a "Survival Under Attack" type government film). If it wants to establish some sort of parallel between the Cold War and Putin's recent annexation of Crimea in Ukraine and his interventionist tactics in Syria, it misses the mark and merely drapes itself in superficial patriotism and family values rather than confront difficult questions posed by the realities of the contemporary world.

Writing about Lincoln in the February 2013 issue of Harper's Magazine, Thomas Frank called Spielberg out in no uncertain terms. I will confine myself to the last two paragraphs here but recommend the entirety:

"Lincoln is a movie that makes viewers feel noble at first, but on reflection the sentiment proves hollow. This is not only a hackneyed film but a mendacious one. Like other Spielberg productions, it drops you into a world where all the great moral judgments have been made for you already – Lincoln is as absolutely good as the Nazis in Raiders of the Lost Ark are absolutely bad – and then it smuggles its tendentious political payload through amid those comfortable stereotypes.

"If you really want to explore compromise, corruption, and the ideology of money-in-politics, don't stack the deck with aces of unquestionable goodness like the Thirteenth Amendment. Look the monster in the eyes. Make a movie about the Grant Administration, in which several of the same characters who figure in Lincoln played a role in the most corrupt era in American history. Or show us the people who pushed banking deregulation through in the compromise-worshipping Clinton years. And then, after ninety minutes of that, try to sell us on the merry japes of those lovable lobbyists – that's a task for a real auteur."

Substitute "Bridge of Spies" for "Lincoln," and Frank's is an excellent review of Spielberg's latest "historical" effort. What Bridge of Spies says about the political zeitgeist – about prisoners at Guantánamo Bay who, unlike Abel who served just over four years of his sentence, will never see a trial; about the deleterious effects of recent Acts of Congress like the Patriot Act (2001) and Supreme Court rulings like Citizens United (2010) – what the movie says about the current moment in relationship to that Constitution Spielberg is so eager to romanticize, is zip.

No comments:

Post a Comment