Emotion and Morality

The idea that emotion directs moral behavior was articulated as early

as the 4th century BCE by Mencius, the most significant interpreter of Confucius. "The feeling of commiseration is the beginning of humanity; the feeling of

shame and dislike is the beginning of righteousness; the feeling of deference

and compliance is the beginning of propriety; and the feeling of right or wrong

is the beginning of wisdom."

The western philosophers of moral sensibility – Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of

Shaftesbury; Francis Hutcheson; David Hume; and Adam Smith – all sought to refute

Thomas Hobbes's mechanistic view of human nature. Hobbes's 1651 Leviathan lays

out a safety net for human interaction that Hobbes calls the social contract – to assure their protection the people agree to accept government, an admittedly artificial political construct, though in doing so they relinquish their own power. Hobbes sees the social contract as a vital necessity for orderly co-existence, but he does not envision rights as inalienable in the Jeffersonian sense. It will be Jean Jacques Rousseau who expands the concept of the social contract to include popular sovereignty, the belief that governmental power emanates from the people, and John Locke who extends the idea to protecting the rights of the individual.

The establishment of the social contract is necessary, Hobbes believes, because without it our

animal nature will inevitably leave us in a state of every man for himself

(and God against all, as Werner Herzog would have it). This egoistic doctrine

of self-interest – the belief that to act in the interest of others is a

violation of human nature and that even actions disguised as sympathy are

actually in service to self-love – troubled 18th century philosophers who tended toward a theory of moral sensibility.

Shaftesbury’s 1699 An Inquiry Concerning Virtue, or Merit espouses a

moral sense theory that both the impulse toward egoism and the impulse toward

altruism are natural, yet imperfect, and must be balanced.

|

| Anthony Ashley-Cooper with his brother Maurice in a 1702 painting by John Closterman designed to illustrate his Neo-Platonist beliefs. (National Portrait Gallery) |

In An Essay on the Nature and Conduct of the Passions and Affections,

with Illustrations on the Moral Sense (1728) and the posthumous System of Moral

Philosophy (1755), Hutcheson (whose family of Scottish Presbyterians are known

as the founding fathers of the Scottish Enlightenment) identifies, in addition

to the five external senses, six internal senses – consciousness, the sense of

beauty, the public sense, the moral sense, the sense of honor, and the sense of

the ridiculous – of which the moral sense is the most important, being

instinctive and immediate, unlike reason, which is mediated.

Hume's An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals (1751) also

provides a naturalistic explanation of morality – that it "depends on some

internal sense or feeling, which nature has made universal in the whole

species." Hume’s moral sense theory, or sentimentalism, is based on a principle

of communication and sharing of sentiments, positive and negative – what we

call empathy – and rejects psychological egoism.

In The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1741), Adam Smith argues that even

as selfish human beings, we are inclined toward pity and compassion. "That we

often derive sorrow from the sorrows of others, is a matter of fact too obvious

to require any instances to prove it; for this sentiment…is by no means

confined to the virtuous or the humane, though they perhaps may feel it with

the most exquisite sensibility."

Shaftesbury, Hutcheson, Hume, and Smith share the view of human beings,

not in isolation, but in community. Shaftesbury believed humans are social

beings and only through virtuous interaction with their fellows can they be deemed

moral. Hutcheson held that actions that flow from self-love alone are morally

indifferent, that only actions that promote "the greatest happiness for the

greatest number" can be regarded as morally good. For Hume, sentiment, because

it is based in sympathy, motivates us to pursue altruistic ends.

From Philosophy to Fiction

Of his novel Sentimental Education (1869), Gustave Flaubert wrote, "I want to

write the moral history of the men of my generation – or, more accurately, the

history of their feelings." The concept of sensibility – the idea that

knowledge comes by way of acute perception that heightens certain individuals' feelings for the world, for others, for beauty and moral truth – entered the

popular culture in the century before Flaubert's through poetry, music and the newly minted novel.

Among the 18th century's freshly fashioned novelistic genres was the Bildungsroman, the novel of the sensitive young man's coming of age. The genre typically involves a traumatic event that occasions the young protagonist to journey into a world whose values he finds hostile. Only by adapting to society through a trajectory from oppression to worldly acceptance can the character reach maturity.

Among the 18th century's freshly fashioned novelistic genres was the Bildungsroman, the novel of the sensitive young man's coming of age. The genre typically involves a traumatic event that occasions the young protagonist to journey into a world whose values he finds hostile. Only by adapting to society through a trajectory from oppression to worldly acceptance can the character reach maturity.

Though the genre has precursors dating as far back as the 12th century,

and is related to ancient quest narratives, its popularity gained momentum

throughout the 18th century in England and France: Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones (1749),

Voltaire’s Candide (1759), Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy (1759), Rousseau’s

Emile (1762), culminating in Goethe’s German masterpiece, Wilhelm Meister’s

Apprenticeship (1795-1796). Indeed, 19th and 20th century German writers

produced exemplary works in the genre from Gottfried Keller’s Green Henry

(1855) and Adalbert Stifter’s Indian Summer (1857) to Robert Musil’s The

Confessions of Young Törless (1906) and Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain

(1924).

No Bildungsroman of the 18th century features a female protagonist

(that I know of), and in the 19th, only Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1830) and

Henry James’s What Maisie Knew (1897) come to mind – in both of which the main

characters determine their fates outside marriage. Jane refuses St. John

Rivers’ proposal (though she will ultimately decide to marry Edward Rochester), and Maisie chooses her guardian over her parents. By and large,

the female protagonist figures in the novel of sensibility rather than in the

Bildungsroman, and her fortunes are determined by the man she does or does not marry.

Her emotions and sensitivity inform her virtue from Samuel Richardson’s Pamela

(1740) to Jane Austen's heroines struggling to balance sense (prudence)

and sensibility (emotion) in their choice of husbands. By the mid-late 19th century, she's cheating her way through men and money like William Thackeray’s Becky Sharp in Vanity

Fair (1847) who ends well and Gustave Flaubert’s Emma Bovary (1856) who makes a

mess of things and ends it all with arsenic, or she is at the mercy of fate (and libertines) in Thomas Hardy's Wessex.

|

| Mia Wasikowska as Jane Eyre in Cary Fukunaga's 2011 film adaptation |

Sentiment and Consumption

Because the protagonist of the Bildungsroman has experienced

persecution, he often grows up to mitigate others' misfortunes, whereas the

protagonist of the sentimental novel grows up to marry, if she is lucky. By the 19th century, however, she

might not get the nuptial chance, for when the nerves of young women of sensibility are over-taxed, they have a tendency

to succumb to illness in one form or another.

Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor was published in 1978. In it Sontag

assaulted the metaphorical uses to which illness is put to turn disease into

mythology. The Romantic poets of the 19th century made consumption an innate psychic state experienced by sensitive artistic spirits possessed of the spiritual

and moral attributes of nobility, creativity, and melancholy. In "Ode to a Nightingale" (1819), Keats's "youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies...." (Keats himself died of tuberculosis in 1821, aged 25 – as did much of his family.) The female consumptive, by contrast, suffers the wasting disease as a natural consequence of her desires. She is sensitive, yes, but she brings her suffering on herself.

Sometimes female characters die because they reject the established social order. Samuel Richardson's Clarissa (1748) succumbs to illness as a result of

her attempts to evade the vile Lovelace’s captivity. In Mary: A Fiction (1788),

Mary Wollstonecraft's only completed novel, Mary's sensibility runs counter to the

conventions of the times, and the ending suggests that, forced as she is to

conform to those conventions, she faces the inevitability of premature death.

Both women are doomed because they seek to live lives of freedom on their own

terms.

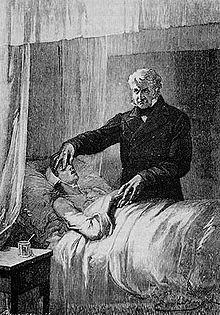

|

| Joseph Severn's "Sketch of the Dying Keats" inscribed: "20 Janry 3 o'clock mng. Drawn to keep me awake - a deadly sweat was on him all this night." |

Just as the philosophical concepts of moral sentiment paved the way for

19th century Romanticism, they laid the groundwork for Freud. From Hippocrates

until the late 19th century, the disorder that went by the name "hysteria" was believed to be a uniquely female malady of sexual

dysfunction. (Greek "hystera" means "uterus.") Freud would alter that view by arguing that hysteria was the

unconscious mind's attempt to shield an individual from psychic trauma, though

he, too, would focus attention on the condition as evinced in women. In literature the manifestation of psychic distress is a literal

disease rather than vague hysteria.

And so the popular imagination, just as

it had venerated female martyrs throughout the ages, was primed by the 19th century to romanticize,

even idolize, the dying heroine, making the dying girl a staple of Romance (with

an upper case "R") novels, Italian opera – and in

our own time, romance (with a lower case "r") novels, young adult lit, and Hollywood tear-jerkers.

Prior to the 20th century most people lived

amidst death with an immediacy that we (that is "we" in first world, affluent

countries) cannot imagine, so it is natural that mortality should inform the

fiction. Disease and dying in literature, however, are disproportionately the province

of heroines over heroes. In Jane

Austen's Sense and Sensibility (1811), Marianne suffers from a "putrid

tendency" (probably typhus). Though she doesn't die, the illness creates a

crisis of sense to bring her back round to sensibility.

|

| The death of Fantine: Valjean (as Mayor Madeleine) closes her eyes. |

The allure of the dying heroine, particularly those wasting away from

consumption, was not exclusive to English writers. Afflicted heroines become standard fare in French literature as well. In Victor Hugo’s 1862 novel Les Misérables, Fantine, having had to resort to prostitution, succumbs to consumption. Another two novels – and the Italian operas adapted from them – feature likewise stricken heroines. In 1848, Alexandre Dumas (fils) created the consumptive Marguerite – based on his lover Marie Duplessis – in The Lady of the

Camellias. The dramatic adaptation became the basis for Giuseppe

Verdi’s 1853 opera La Traviata. Violetta, a consumptive courtisane, moves among the aristocracy but their wealth and

status cannot save her.

Three years after Dumas’s novel, Henri Murger, best known for his poem

“La Chanson de Musette,” penned the episodic novel La Vie de Bohème with Mimi,

another consumptive heroine, at its center. Giacomo Puccini adapted the novel into

the late-Romantic opera La Bohème, which premiered in 1896. The wan youths of the Romantic poets and then Romantic heroines like Marguerite/Violetta and Mimi gave consumption the cachet Sontag so vociferously excoriated. Indeed the English poet Lord Byron declared, “I should like to die from

consumption.” (He would die instead of banal sepsis from unsterilized bloodletting instruments.) La

Traviata and La Bohème remain among the most performed operas across the globe to this day,

attesting to the allure of the tragic heroine dying in the fullness of youth.

To say Dumas’s courtisane has legs is understatement. In addition to many Camille stage adaptations, there are the musical adaptations – the

2008 production Marguerite set in 1944 Vichy France and Baz Luhrmann's 2001 film Moulin

Rouge! with Nicole Kidman set at the fin de siècle.

|

| Baz Luhrmann's 2001 Moulin Rouge! with Nicole Kidman: Satine's death scene |

The Lady of the Camellias has been dramatized in dance as well. In 1963 Sir Frederick

Ashton premiered his choreography specially created for Rudolph Nureyev and

Dame Margot Fonteyn, Marguerite and Armand. Veronica Paeper premiered her Camille in 1990, which has been performed

ever since; and Lady of the Camellias set to music by Frédéric Chopin was

choreographed for Marcia Haydée by John Neumeier in 1978 and for Ballet Florida

by Val Caniparoli in 1994.

Silent films include the 1907 Danish Kameliadamen with Oda Alstrup; the

1911 French La Dame aux Camélias with Sarah Bernhardt; the 1915 Italian La

Signora delle Camelie with Hesperia; a 1921 English version with Nazimova and

Rudolph Valentino; and the 1925 Swedish Damen med kameliorna with Tora Teje.

The first sound adaptation was the 1934 La Dame aux Camélias adapted by

Abel Gance and directed by Gance and Fernand Rivers with Yvonne Printemps and

Pierre Fresnay; then George Cukor’s 1936 Camille with Greta Garbo and Robert Taylor; a 1944

Mexican Camelia with Lina Montes and Emilio Tuero; the 1953 French La Dame aux

Camélias with Micheline Presle and Gino Cervi; the 1954 Mexican Camelia with María Félix and Jorge Mistral; the

1954 Argentinean La mujer de las camellias with Zully Moreno and Carlos Thompson; a 1957 Turkish Kamelyalı

Kadın with Çolpan İlhan and Fikret Hakan; yet another French version, the 1981 La Dame aux

Camélias with Isabelle Huppert and Gian Maria Volonté; and a 1994 Polish Dama Kameliowa with Anna Radwan and Jan Frycz.

|

| Greta Garbo and Robert Taylor in George Cukor's 1936 Camille |

And then there was Eric Segal's book and Arthur Hiller's movie adaptation of Camille that

besotted teen girls throughout the 1970s: Love Story. (Film critic Judith Crist called Love Story,"Camille with bullshit.") By this time, Love Story absurdly and vacuously makes the claim that "Love means never having to say you're sorry," and the

disease du jour has changed from consumption to the scourge of our era – cancer,

specifically in Love Story's case, leukemia.

| Arthur Hiller's 1970 Love Story |

Maladies in the Movies

(NB: The criteria for the films

under discussion do not allow the central character to be a child or elderly,

but young or relatively young – even middle aged – characters ailing from disease, and do not allow for Christian

or Nicholas Sparks movies.)

In contrast to the more vague – and romantic – diagnosis of "consumption," post-19th century fiction is predominated by cancer, identified

with increasing specificity as time has gone by. Judith Traherne (Bette Davis) in Edmund

Goulding's 1939 Dark Victory suffers from a brain tumor, and the film goes to

some lengths to incorporate the medical terminology of the day. In Gary

Marshall's 1988 Beaches, Hillary Whitney (Barbara Hershey) is dying of viral

cardiomyopathy; in Pat O'Connor's 2001 Sweet November, Sara Deever (Charlize

Theron) is dying of Non-Hodgkin lymphoma; in Ol Parker's 2007 Now Is Good, Tessa

Scott (Dakota Fanning) is dying of acute lymphoblastic leukemia; and in Josh

Boone's 2014 The Fault in Our Stars, Hazel Lancaster (Shailene Woodley) is

dying of thyroid cancer that has spread to her lungs.

|

| Bette Davis and Humphrey Bogart in Edmund Goulding's 1939 Dark Victory |

Sontag held that in the 20th century, cancer patients are characterized

as emotionally repressed, pessimistic loners. Again, the popular culture has

more often than not gendered the stereotype, and the young women dying of

cancers in the movies far outweigh the young men. I came up with only a few films that treat a young man's impending death from cancer from a purely dramatic

perspective, the earliest of which was Joel Schumacher's 1991 Dying Young.

Others include Bruce Joel Rubin's 1993 My Life; Wendell Morris's 2001 The

Medicine Show; Chris Kraus's 2002 Shattered Glass; Patrice Chéreau's 2003 Son

frère; Todd Kessler's 2008 Keith; and Conrad Jackson's 2011 Falling Overnight.

Filmmakers seem to feel more at ease wedging dying male characters

into more comfortable tropes like the Buddy Movie: Neal Israel's 1992 Breaking

the Rules; Judd Apatow's 2009 Funny People; Jonathan Levine's 2011 50/50; and the German director Thomas Jahn's 1997 Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door, in which two hospital patients, both of whom have what we are only told is an

untreatable disease, go on a picaresque spree.

|

| Martin Brest and Rudi Wurlitzer in Thomas Jahn's 1997 Knockin' on Heaven's Door |

The two films with dying men that come closest to reflecting the redemptive character type are Irwin Winkler's 2001 Life as a House, in which Kevin Kline's disagreeable architect

ultimately functions as a catalyst of grace for his family, and Alejandro González Iñárritu's 2010 Biutiful, in which the rumpled,

beatific Javier Bardem is cast as something of a modern-day shaman/saint.

I have excluded films like Bill Sherwood's 1986 Parting Glances, Jonathan Demme's 1993 Philadelphia, and Joe Mantello's 1997 Love! Valour! Compassion! – based on Terrence McNally’s 1994 play – where the protagonist is dying of AIDS, because the AIDS drama has evolved into something of a genre unto itself, and its central characters, as men, exhibit more obstinacy and resolve than their wasting female counterparts.

I have excluded films like Bill Sherwood's 1986 Parting Glances, Jonathan Demme's 1993 Philadelphia, and Joe Mantello's 1997 Love! Valour! Compassion! – based on Terrence McNally’s 1994 play – where the protagonist is dying of AIDS, because the AIDS drama has evolved into something of a genre unto itself, and its central characters, as men, exhibit more obstinacy and resolve than their wasting female counterparts.

|

| Javier Bardem in Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu's 2010 Biutiful |

In contrast to Hobbes's belief that without a social contract our animal nature will inevitably leave us in a state of anarchic chaos were philosophers who believed not only that emotion and its attendant morality are inherently human, but that empathy is universal and bound up in feeling. The Bildungsroman was, and to some extent still is, predominantly the province of male protagonists, the sentimental novel the province of heroines: men make their way in the world, women marry – or die. The Romantics pathologized feeling and introduced the young man whose nearness to death heightens his sensitivity, making him a conduit of transcendent insight. Also pathologized is the young woman who resists marriage and has little to teach us of transcendent worlds. His sickness is a result of his creative soul, hers the result of her resistance to her proper place in nature.

Dying Alone

Part of the dramatic appeal of La Traviata and La Bohème and their heirs (including Jonathan Larson’s 1996 musical Rent, which transports La Bohème into an East Village, HIV-positive gay theater milieu) is the demi-monde community that circulates around their protagonists. The 20th and 21st century dying girl is surrounded by much smaller casts of supporting dramatis personae. She may only have a boyfriend or husband at her side (Love Story), maybe a best friend (Beaches), or estranged members of a nuclear family (James Brooks's 1983 Terms of Endearment adapted from Larry McMurtry's 1975 novel).

Dying Alone

Part of the dramatic appeal of La Traviata and La Bohème and their heirs (including Jonathan Larson’s 1996 musical Rent, which transports La Bohème into an East Village, HIV-positive gay theater milieu) is the demi-monde community that circulates around their protagonists. The 20th and 21st century dying girl is surrounded by much smaller casts of supporting dramatis personae. She may only have a boyfriend or husband at her side (Love Story), maybe a best friend (Beaches), or estranged members of a nuclear family (James Brooks's 1983 Terms of Endearment adapted from Larry McMurtry's 1975 novel).

|

| Emma Thompson as Vivian Bearing in Mike Nichols's 2001 adaptation of Margaret Edson's 1995 play |

The character who goes it solely alone is Vivian Bearing, a scholar of metaphysical poet John Donne, in W;t, Margaret Edson's 1999 Pulitzer Prize-winning play adapted by director Mike Nichols and actress Emma Thompson into the 2001 Emmy Award-winning television drama. On its surface, W;t might seem to break the trope of the dying heroine, but in reality it only reinforces it. In one of the best analyses of W;t I have read, Jacqueline Vanhoutte of the University of North Texas places the play squarely in the midst of the dying heroine metaphor with all its trappings, most notable among them that Vivian's intellectual rigor is the root cause of her cancer and that her suffering provides the catalyst for her redemption. Vanhoutte cites the Shakespearean scholar A. C. Bradley: tragedy necessitates "calamities and catastrophe follow inevitably from the deeds of men." From that premise, Vanhoutte argues that "to make a cancer patient the subject of a tragedy is to reproduce and legitimate the 'moralistic and punitive' fantasies about cancer that Sontag describes."

"Edson proposes," Vanhoutte continues, "that, in privileging reason over emotion, 'research' over 'humanity,' Vivian has pursued a course that ensures her 'immense success' as an academic even as it proves detrimental to her health." Treated as an object of research with a piteous absence of compassion, Vivian comes to realize that intellectual rigor (sense) is a barrier to kindness (sensibility).

In the previous essay I said that Me and Earl and the Dying Girl comes at the sentimental trope of the deathbed heroine obliquely and makes it into something else, something larger. Rather than a movie about a dying girl, it is a story about art, a story about the stories we tell, a story about the idea that in doing and making we transcend mortality. And focusing as it does on "ME," Me and Earl and the Dying Girl is not a story of sentiment but a modern-day Bildungsroman, in which the dying girl is an impetus for the young man's coming of age.

The Redoubtable Woman Instead

Dying is universal and profound so we are bound to tell stories about it, but aside from being sad, the dying girl trope is too often pretty shallow – and sexist. There is sometimes something even prurient about it. The dying girl notwithstanding, independent heroines have been out there – for centuries. In the 6th century Chinese poem, The Ballad of Mulan, a 17-year-old goes to war in her father's stead and triumphs in battle again and again. She has been variously imagined since, most recently and unfortunately in 1998 as a bumbling Disney animated character. Chaucer invented the bawdy Wife of Bath in the 14th century, who would become the most memorable of his pilgrims. There are the various heroines of YA trilogies, and there is that Nordic goth of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2005), Stieg Larsson's Lisbeth Salander, brilliant computer hack and rebellious outsider.

In America's Women: Four Hundred Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines, Gail Collins observes that "Some of our national heroines were defined by the fact that they never nested – they were peripatetic crusaders like Susan B. Anthony, Clara Barton, Sojourner Truth, Dorothy Dix." Let's tell more stories – not biopics about these actual women necessarily – but stories about strong, imagined women like them. Doing so would deepen and enrich our understanding not only of our female compeers but of our collective human psyche.

"Edson proposes," Vanhoutte continues, "that, in privileging reason over emotion, 'research' over 'humanity,' Vivian has pursued a course that ensures her 'immense success' as an academic even as it proves detrimental to her health." Treated as an object of research with a piteous absence of compassion, Vivian comes to realize that intellectual rigor (sense) is a barrier to kindness (sensibility).

In the previous essay I said that Me and Earl and the Dying Girl comes at the sentimental trope of the deathbed heroine obliquely and makes it into something else, something larger. Rather than a movie about a dying girl, it is a story about art, a story about the stories we tell, a story about the idea that in doing and making we transcend mortality. And focusing as it does on "ME," Me and Earl and the Dying Girl is not a story of sentiment but a modern-day Bildungsroman, in which the dying girl is an impetus for the young man's coming of age.

The Redoubtable Woman Instead

Dying is universal and profound so we are bound to tell stories about it, but aside from being sad, the dying girl trope is too often pretty shallow – and sexist. There is sometimes something even prurient about it. The dying girl notwithstanding, independent heroines have been out there – for centuries. In the 6th century Chinese poem, The Ballad of Mulan, a 17-year-old goes to war in her father's stead and triumphs in battle again and again. She has been variously imagined since, most recently and unfortunately in 1998 as a bumbling Disney animated character. Chaucer invented the bawdy Wife of Bath in the 14th century, who would become the most memorable of his pilgrims. There are the various heroines of YA trilogies, and there is that Nordic goth of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2005), Stieg Larsson's Lisbeth Salander, brilliant computer hack and rebellious outsider.

|

| Hua Mulan |

No comments:

Post a Comment