We are not provided with wisdom, we must discover it for ourselves, after a journey through the wilderness which no one else can take for us, an effort which no one can spare us, for our wisdom is the point of view from which we come at last to regard the world.

~~Marcel Proust,

In Search of Lost Time Vol. II:

Within a Budding Grove, 1919

On the way to lunch in a colleague's car a song popped up from his iTunes collection, and he remarked how great was the lyric "I don't want to grow up." To cite it, I googled for the lyric and instead found a myriad of songs with essentially the same title: "I Don't Want to Grow Up" (1985) by the Descendents; "I Don't Wanna Grow Up"

(1992) by Tom Waits and covered by the Ramones (1995);

"Don't Wanna Grow Up" (2003) by the Sacramento-based Willknots; "Don't Grow Up" (2010) by Taylor Swift; and in lyrics rapper Machine Gun Kelly appended in 2013 to Rise Against's

"Swing Life Away" (2004): "I don't want to grow up don't nobody

like you when you're 23."

The sentiment of these songs – "I don't want to be like you... You're a fool"; "I'd rather stay here in my room"; "I don't want to figure [adulthood] out"; "Wish I'd never grown up" – differs from the pop standard "Young at Heart" (1953) popularized by Frank Sinatra among others or Bob Dylan's ballad "Forever Young" (1972). "Young at Heart" may be a little cloying but it celebrates determination and the acceptance of failure with grace. "Forever Young" is a litany of hopes: May you be generous, humble, creative, righteous, true, courageous, strong, engaged, and grounded. It is an anthem, a hymn, a prayer. Neither songs' lyrics reject work, responsibility, community, and self-awareness.

There was a time when men and women made headway in their 20s toward life's milestones. In the last several decades, however, social scientists have

been scrambling for a terminology – "emerging adulthood," "delayed

adolescence" – to describe the decade from 20 to 30. Judging by popular culture, attire, and leisure activities –

reliable reflections of the zeitgeist all – after 30 and even well into their 60s many Americans

have no aspirations to become adults, indeed strenuously avoid it.

There's no need to cite examples (suffice it to say that a sitcom

actually called

Arrested Development about the culture of

McMansions, materialism, and psychological manipulation ran from

2003-2006 and was revived for an additional season in 2013 on Netflix);

the attitude is ubiquitous in advertising, television, movies, video games, politics –

even churches struggle to be more "relevant," i.e. youth oriented.

I am not mounting a defense of tradition. Both marriage and children have the potential to

feel like albatrosses and too many harness themselves with one, the other, or both for all the wrong reasons. These days, education can translate into staggering student loans that can be a financial burden for decades to come, and home "ownership" is a euphemism for equally burdensome debt. What I find wanting in a society

permeated with the permanence of adolescence and resistance to

responsibility and self-sufficiency is the abdication of growth itself –

of curiosity and achievement, of what it means to be human, of physical and psychological maturation. If untethered twenty-somethings were making conscious

decisions to become contemplatives, I could respect self-sacrifice in the quest for enlightenment. If they were taking political action by joining collectives and removing themselves from the grid, I'd say, more power to you. If they were joining the Peace Corps, volunteering at homeless shelters, or giving music lessons to at-risk kids, or, or, or... I could applaud. Instead, many unreconstructed

adolescents don't seem to be doing much of anything at all.

The golden myth of America as the land of possibility galvanized wave

after wave of immigration through the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Hard work and ingenuity were encouraged, admired, and often rewarded.

Then the mounting excesses of the

fin de siecle financial class brought

the house down on Black Tuesday 1929, and what had already been a hard life for many became harder still. Franklin D. Rooselvelt's New Deal notwithstanding, many

economist argue that without World War II, the United States economy would not have recovered, but recover it did.

The war brought Americans together in solidarity and shared self-sacrifice. That sense of belonging persisted after the war as the United States experienced unprecedented prosperity due in no

small part to the passage in 1944 of the G.I. Bill, which provided money

for college education, small business investment, and home mortgages.

In the next decade, Dwight D. Eisenhower championed the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 and

the National Aeronautics and Space Administration in 1958. Despite a growing military presence in south Asia, the '60s dawned as John F.

Kennedy campaigned for what would become the ambitious Apollo manned

space program. Together union advocacy, FDR's safety net programs like Social

Security, the G.I. Bill, infrastructure investment, and

the research and development programs of the '50s and '60s paved the way

for middle class upward mobility.

Through the 1950s and '60s, the nation rode a wave of optimism that

experienced its first serious abatement in 1973, ebbed and

flowed throughout the 1990s and 2000s, until the bubble burst again in

2008. While the bottom of the heap has yet to recover from the Great Recession, the people at the top have done just fine, and the people in the middle –

whatever "middle" means these days –

have managed. They and

their children have never experienced –

nor witnessed –

the

kind of destitution openly on view across the nation in the 1930s. We have found ways to put

those unable to participate in prosperity out of sight –

and

therefore, out of mind.

Optimism and prosperity have devolved into self-absorption, rapacity at one end of the scale and torpor at the other, and an unprecedented sense of entitlement. If aging has not been turned into a sin, it has at the very least become a vice. Not surprisingly, today's movies are

filled with juvenile characters of all ages because arrested development is the prevailing predisposition of our era. This year some

of the movies that touched on these phenomena were remarkably good, some were mediocre, but they all

demonstrate the pervasiveness of childish adults accustomed,

or hoping to become accustomed, to lives unburdened by responsible behavior. Without

affluence you have to grow up. Without material comforts, life is hard

and unforgiving.

Of the many archetypes identified by Carl Jung,

puer aeternus – Latin "eternal boy" – dominates the American psyche and has become a Hollywood staple. At its best the

puer aeternus represents the Divine Child from whom we derive a sense of possibility and hope, "the boy who is born from the maturity of the adult man, and not the unconscious child we would like to remain," as Jung says in

Answer to Job. This is what Dylan means by "forever young." At its worst the

puer aeternus suggests, not eternal youth, but arrested development – unchecked impulses, carelessness, indiscretion, narcissism, and callousness toward others.

The man-child is no longer the exclusive purview of the male. Melissa McCarthy has practically created her own franchise out of the immature woman, this year adding

Tammy to the collection. Judd Apatow, who codified the man-child movie and was strangely absent from this year's offerings, astutely realized he was missing the pocketbooks of half the population and remedied his oversight in 2011 with

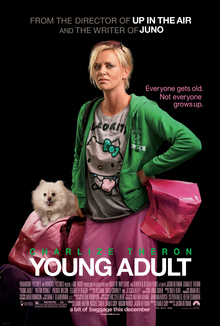

Bridesmaids. The same year Jason Reitman offered a rare serious – and searing – examination of this phenomenon. In

Young Adult, Charlize Theron gives a riveting performance as a young adult fiction writer whose fans have moved on to the next new thing. Unable to distinguish make-believe from reality, she embarks on a stalker's mission to realize her high school sweetheart fantasies. Though

Young Adult garnered critical praise, very few people saw it.

This year was awash in movies that make arrested adolescence the center of attention. Jason Bateman directed and starred in

Bad Words in which a grown man robs children of spelling bee championships. Not having graduated from eighth grade, he (obnoxiously) argues he is not breaking any rules. Richard Shepard's

Dom Hemingway stars Jude Law as a profoundly irresponsible, now ex-con, hell-bent on resuming every bad habit he's ever indulged including manipulating the emotions of his grown daughter.

Roger Mitchell's

Le Week-End has Jim Broadbent and Lindsay Duncan in complexly realized performances as Nick and Meg who ostensibly arrive in Paris to celebrate their anniversary. Their marriage has become a bittersweet affair with the emphasis decidedly on bitter, a fact that becomes ever more apparent as they skip out on meals they can't pay for, move into a hotel they can't afford, and plaster the walls of the room with clippings from art books they've maxed out their credit cards to buy.

|

| Jim Broadbent and Lindsay Duncan in Le Week-End |

In John Carney's

Begin Again,

Mark Ruffalo's Dan is a

washed up record producer whose routine of booze, sleep, and hangovers

infringes on accomplishing much of anything – until his muse in the

guise of Keira Knightly enters the scene, and they can romp about the

city making impromptu recordings and as much noise as they please, city ordinances be damned.

Two lovely little movies were

Obvious Child and

The Skeleton Twins. Donna Stern (Jenny Slate) in Gillian Robespierre's

Obvious Child has the otherwise nonexistent movie wisdom to have an abortion, being self-aware enough to know she does not possess the maturity to be a mother. In an earlier era, she might not have had the luxury of that choice nor the sense of entitlement and affluent family that allow her to pursue a career as a standup comedian. Sanctioning abortion as a choice in a Hollywood movie is a welcome breakthrough, and

Obvious Child is a nice little indie-esque film, but it would be nicer to see a mature character make a similar choice for more complex reasons.

|

| Jenny Slate in Obvious Child |

The twins in Craig Johnson's

The Skeleton Twins have depression in common, one source of which

may be that sense of entitlement they share with the other characters here. Kristen Wiig and Bill Hader deliver exceptionally nuanced performances as Maggie, a dental hygienist in upstate New York, and her brother Milo, who comes to live with her after his failure in the pursuit of an acting career in LA leads to a suicide attempt. Suicide is, after all, the surest way to avoid growing up.

|

| Kristen Wiig and Bill Hader in The Skeleton Twins |

When we meet Eleanor in Ned Benson's tale of loss

and possibility dashed, she, too, is recuperating from a

suicide attempt,

estranged from her husband, and living with her French mother and

academic psychologist father (Isabelle Huppert and William Hurt). We

will not know what tragedy has driven her actions until later in

The Disappearance of Eleanor Rigby, but we sense it was profound. I can't suppress my exasperation, however, with a character whose self-absorption is absolute and who has unlimited economic means to drift. Despite a tragedy that encompasses all of the characters in the film, none exhibit much depth and hardly any compassion for the people around them. This is another cast

of players buffered by affluence and excused by a general climate of

anomie.

|

Jessica Chastain and James McAvoy

in The Disappearance of Eleanor Rigby |

The greatest offender of this year's lot is Megan (Keira Knightly) of Lynn Shelton's

Laggies. Closing in on 30, she's finished her degree in psychology but doesn't have the empathy to listen to other people's problems. She lives with her boyfriend but prefers to hang out on her parents' couch. Despite her aimlessness, he asks her to marry him, to which she says yes. She then proceeds first to hang out and then to hide out with some high school kids she meets when they ask her to buy liquor for them, which she does because... well, because it's the irresponsible thing to do. And that's OK, America's movie-going audience seems to say, because we don't expect our characters, any more than we expect ourselves, to behave responsibly.

|

| Keira Knightly and Chloë Grace Moretz in Laggies |

I saved the most annoying –

Hector and the Search for Happiness – and, at least on its surface, the oddest –

Dear White People – for last.

The only contemporary phenomenon as ubiquitous as arrested development is the sense that happiness is an entitlement. I hesitate to blame Thomas Jefferson for this. After all, Jefferson never said that among our unalienable rights is happiness – only the

pursuit of happiness. Nonetheless, we feel we have the right, and to that end therapists, self-help gurus, and book publishers have made a fortune. Google "books on happiness" and find not individual titles, but hits like "Amazon Best Sellers: Best Happiness Self-Help," "7 Essential Books on the Art and Science of Happiness," "Best Happiness Books (121 books) - Goodreads," "Must-Read Books on Happiness - Business Insider,"

ad infinitum...

French psychiatrist François Lelord wrote a trilogy of Hector books from 2002-2006 of which

Hector and the Search for Happiness is the first. It was followed by

Hector and the Secrets of Love and

Hector and the Search for Lost Time. Speaking of affluence and anomie, despite learning from one of his patients that Hector's prices have not gone up along with other shrinks’, his life looks pretty darned well-heeled as do those of his private practice patients. Like the equally shallow

Eat, Pray, Love,

Hector and the Search for Happiness is just as unencumbered by economic limitations. Ah, that we could all globe-trot indefinitely in search of enlightenment and be asked to sacrifice so little along the way.

|

| Simon Pegg as Hector in Hector and the Search for Happiness |

I think I wanted to like Peter Chelsom's adaptation because the trailer brought to mind Tintin, the wonderful creation of Belgian cartoonist Hergé (George Remi), whose adventures as a precocious child investigative reporter take him round the globe to exotic locales and land him in hair-raising escapades. The syntax of the

Hector title itself echoes Tintin –

Tintin and the Secret of the Unicorn,

Tintin and the Picaros – but also evokes, Proust notwithstanding, academic titles like

Science and the Search for God or

Suffering and the Search for Meaning or whatever is on the tables at your Barnes and Noble right now. Yet Tintin, unlike Hector, is a boy wearing the mantle of a man, consciously charging toward responsibility and risk. Tintin is self-possessed; he does not chase down adventure in an attempt to "find himself."

Simon Pegg even looks a bit like a not too grownup Tintin, and we get a cute-as-can-be Boston terrier to substitute for Tintin's trusty white wire fox terrier, Snowy, whenever Hector goes to his inner child. But the adult Hector remains as much a naïf as that inner child – which was perhaps meant to be endearing but instead is just irritating.

To say the series of adventures he encounters is implausible is an understatement. Nonetheless, the point would seem to be that Hector learn something, gain some insight through the journey. Unfortunately, the observations he records in his journal almost make Hallmark platitudes sound deep and reveal nothing that should not be within the innate grasp of a three-year-old. All this is to say, let us hope and pray no misguided soul decides to complete the trilogy.

Justin Simien’s

Dear White People (which could be subtitled

No, Virginia, there is no post-racial America...) oozes affluence across racial lines, and the question of identity (racial, sexual, political, gender) is its springboard. Set in a fictional Ivy League university, it is about political power struggles but political power struggles within an elitist, rarefied world. Racial tensions intensify when the administration decides the university should abandon its traditional policy of specialty dorms in the name of diversity, though the only dorm profoundly affected by that decision will be the school’s historically black residence hall. The euphemistic term the administration has devised for the strategy is “randomization.”

|

| Dennis Haysbert as the dean of students and Brandon P. Bell as his son, Troy |

All the usual collegiate suspects are here. The clueless college

president (white); the long-suffering dean of students (black); the

entitled president’s son who heads up the campus Harvard Lampoon-like

humor magazine; the gang of scatological frat boys; the dean’s son, a

big man on campus and the black

residence hall's elected representative who dates a white girl – all of whom Simien fails to

develop into anything more than types.

At the center are the only two fleshed out characters: the mixed-race student activist and the gay guy. The former is Samantha White (Tessa Thompson) who does the campus radio show of the title where she bluntly calls out white people’s hypocrisy with observations that should be self-evident, yet unfortunately for too many are not. This persistent absurdity is the source of the satire on which the movie hinges. (To wit: Dear White People, A white girl dating a black guy to get back at her parents is not cool.)

|

| Tessa Thompson as Sam in Dear White People |

The latter is aspiring journalist Lionel (Tyler James Williams) whose small frame is dwarfed not so much by an Afro as by hair he altogether neglects. Both are outsiders from beyond the white/black dichotomy Simien sets up and all the more welcome for it. Neither is defined by his/her outsider status as gay or mulatto. Sam undertakes a struggle to find her authentic self, but Lionel seems always to have been comfortable with who he is. He functions as the anchor of this story because he seems never to have thought of himself as black or gay or anything other than Lionel, a person he genuinely likes and respects.

|

| Tyler James Williams as Lionel in Dear White People |

Sam and Lionel are also the only characters in

Dear White People, black or white, who actively eschew that overarching sense of entitlement

.

Having established his narrative in lap of luxury academe, Simien's

conceit fails to deliver a sharpened understanding of the dynamics

between the juxtaposed characters. They're all well-off, which puts them

at a remove from most of us, though Sam and Lionel may be a tacit nod to affirmative action, or at least to economic diversity, as is the character driving the film's weakest plot line. Native south side Chicagoan Coco (Teyonah Parris) is careful not to let on to her roots. She hopes to improve her chances of making it into reality TV (as realistic as the kid who thinks she's going to be a fashion model or thinks he's going to be an NBA basketball player) by convincing the magazine’s white annual party organizers to theme their bash around blackface, which she plans to podcast.

|

| Teyonah Parris as Coco in Dear White People |

That this plot twist is inspired by numerous campus events around the country where this has actually occurred – still occurs – is not enough to make it work. It would have been more productive to move the plot using more subtlety and depth. Even so, something’s happenin’ here, even if what it is ain’t exactly clear…. (I include this

link to Richard Brody’s piece for the New Yorker, which is hands down the best review of

Dear White People out there.)

Earlier I remarked that what I find dispiriting about a society in thrall to adolescence, hostile to responsibility, and antagonistic to aging is the abdication of what it means to be fully human and engaged. No matter how hard we try to keep it at bay, age will come, and clichés aside, as Oscar Wilde warned, "sometimes age comes alone" sans wisdom. A central concern of the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke was the

process of becoming, the constant evaluation of processes as an artist specifically and the process of becoming that is the arc of one's life in the larger sense. In

Letters to a Young Poet (written between 1902-1908) Rilke writes, "Live your questions now, and perhaps even without knowing it, you will live along some distant day into your answers."

|

| Kaitlyn Dever as Jayden and Brie Larson as Grace in Short Term 12 |

We need more characters who are engaged and willing to be vulnerable to experience – and they are not the teens of young adult trilogies who are really just another manifestation of our love affair with extended childhood and our collective cultural inertia. Contemporary dystopian and superhero narratives would have us believe we can just sit back because surely there are heroes in our midst destined to save us from the totalitarianism and ecological disasters a parents' generation has wrought. Fantasy is escapist not exemplary. Last year I was fortunate to have Destin Daniel Cretton's

Short Term 12 show up in my theater. Grace and Mason are twenty-somethings who manage a short term teen foster care facility. They work patiently to deflect the pain and puncture the armor of the wounded souls who come to them. These are the kinds of quietly brave characters I long to see more of.

No comments:

Post a Comment