In Land Ho!, directors Aaron Katz and Martha Stephens bring off a couple of feats. The movie is a remarkable piece of cinema verité. Especially seeing the trailer, you are convinced you are watching a documentary. In feature length, it reads more like a created work but still possesses a feeling of simplicity and lack of artifice that were probably more challenging to achieve than we might imagine. Much of Land Ho!’s charm derives from its retiring co-stars Paul Eenhoorn and Earl Lynn Nelson.

|

| Paul Eenhoorn and Earl Lynn Nelson in Land Ho! |

Think The Big Wedding with Diane Keaton, Robert De Niro, and Susan Saradon. Despite some wonderfully nuanced performances as an older character in movies like Everybody’s Fine and Silver Linings Playbook, De Niro has become a staple of the old coot genre as a regular in the Fockers franchise, as well as in coot-as-unreconstructed-adolescent vehicles like Grudge Match and Las Vegas, which also stars Morgan Freeman and, it pains me to say, Kevin Kline.

Upon the girl's arrival, a man not so discreetly departs the house as Wanda resumes her drink, lights another cigarette, and soon tells her niece that her name is not Anna but Ida Lebenstein – she is a Jew.

Michael Douglas and Diane Keaton teamed up this year in the barely okay And So It Goes, for which Sissy Spacek had the great good sense to turn down the Keaton role. Jane Fonda doesn’t have a great track record of late either. Grace in Peace, Love, and Misunderstanding and Hillary Altman in This Is Where I Leave You – remove the love beads from the former and the tchotchkes from the latter – are one and the same role. If we ignore the Focker mess, Barbra Streisand has exercised better judgment with little movies like last year’s The Guilt Trip, which brings us back to the road.

Land Ho! is the classic road movie, by which I do not mean that the characters are simply on the road, but that the trip unwittingly, at least at first, becomes the most ancient trip of all, the quest. Setting off on a journey into the unknown is the catalyst by which the hero (or antihero) gains self-knowledge.

|

| Paul Eenhoorn and Earl Lynn Nelson in Land Ho! |

Eenhoorn and Nelson are Colin and Mitch, longtime friends by marriage. (Colin’s wife died; her sister divorced Mitch.) Colin has become accustomed to being alone, and one senses that even before his wife's death, he was a quiet sort. Mitch is randier and has not caught up with political correctness. Mitch has bought them tickets for a vacation in Iceland without telling Colin, which leaves Colin understandably miffed, but Colin is such a thoughtful man, he soon succumbs to his old friend’s enthusiasm.

What follows is a gentle journey of self-discovery and a kind, thoughtful glimpse into two aging individuals’ friendship, something Americans too often refuse to examine with anything less than inanity.

The Trip to Italy

In The Trip to Italy, Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon reprise their culinary junket to northern England in Michael Winterbottom’s 2010 The Trip. Neither is an epicure, yet they do not turn down the London Observer’s all-expense paid trips to stay in antiques-appointed hotels and dine on celebrity chef haute cuisine. All the while their improvisations are riffs on literature, culture high and low, and involve one upping each other in exacting impersonations.

Whereas much of Land Ho!’s warmth and sensibility emerges from its realistic style, Winterbottom, Coogan, and Brydon set up a thespian conundrum as to whether the two actors are a) themselves, b) playing themselves, or c) playing characters who coincidentally have the same names and manner.

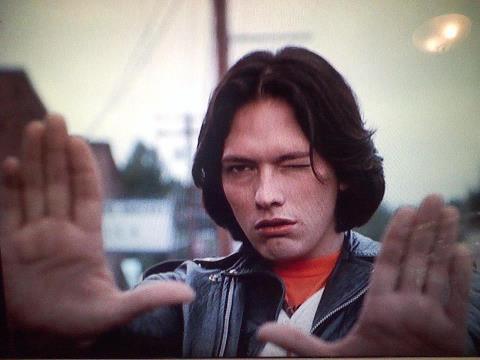

|

| Earl Lynn Nelson as Mitch in Land Ho! |

The Trip to Italy

In The Trip to Italy, Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon reprise their culinary junket to northern England in Michael Winterbottom’s 2010 The Trip. Neither is an epicure, yet they do not turn down the London Observer’s all-expense paid trips to stay in antiques-appointed hotels and dine on celebrity chef haute cuisine. All the while their improvisations are riffs on literature, culture high and low, and involve one upping each other in exacting impersonations.

|

| Rob Brydon and Steve Coogan in The Trip to Italy |

Britisher Winterbottoms’s The Trip and The Trip to Italy, like the indie Land Ho!, make something meaningful out of a comedy about male friendship, unlike the man-boy vehicles Hollywood churns out like Dumb and Dumber, Bill and Ted, 21 Jump Street, et al. ad nauseum. Ultimately, it’s not about the food, or Italy, or who does a better Michael Caine – it’s about an old friendship in which each man, seeing his own advancing age in the other, clumsily, obliquely communicates his gratitude to the other.

Ida

Considering the cinema verité illusion of Katz and Stephens’ Land Ho! and the complete blurring of the line between documentary and fiction in Winterbottom’s The Trip to Italy, it is interesting to note that Pawel Pawlikowski began his film career as a documentarian for British television. That said, what he has created in Ida is an austerely crafted tale of innocence and experience.

With Ida, Pawlikowski returns to the past – to his native Poland

geographically and to Poland’s past historically. Set in the early

1960s, Ida is a Bildungsroman about a young novitiate, an orphan who has

grown up in a convent apart from the world and apart from her own

identity. The Mother Superior believes she must understand what she is

giving up; otherwise, taking religious orders will involve no meaningful

sacrifice.

|

| Rob Brydon and Steve Coogan in The Trip to Italy |

Ida

Considering the cinema verité illusion of Katz and Stephens’ Land Ho! and the complete blurring of the line between documentary and fiction in Winterbottom’s The Trip to Italy, it is interesting to note that Pawel Pawlikowski began his film career as a documentarian for British television. That said, what he has created in Ida is an austerely crafted tale of innocence and experience.

|

| Agata Trzebuchowska as Ida |

The Mother Superior tells the girl she must visit her only relative, an aunt who

lives in Lodz, before she will be allowed to take her vows. Dutifully,

Anna sets off to meet a complete stranger who is in many ways her

diametrical opposite. Indeed, the young innocent will confront who

she will be in the world, and her aunt Wanda, the cynical adult, will confront

who she has been in the fallen world of corruption and disgrace.

|

| Agata Kulesza as Wanda in Ida |

As the two become acquainted we learn that Wanda was a state prosecutor in the brutal government of the Polish People’s Republic, which stopped at nothing to root out anyone even dubiously suspected as traitorous. Ida, unintentionally at first and then with precise volition, undertakes her initiation into the worldly, while Wanda sets about to confront her past and enlists Ida in a road trip with a very specific destination in mind.

For such a short film (Ida clocks in at a mere 80 minutes), Pawlikowski’s spare script and Lukasz Zal and Ryszard Lenczewski’s sparse and beautifully composed black and white cinematography manage to juxtapose, with no overt display, the historic macrocosm of the tragic pall of the Holocaust – the end of which only exacted a furtive day to day life under the shadow of Polish communism – against the microcosm of the intersection of the two women’s lives.

New York Times film critic A. O. Scott astutely observes that “Ida has some of the structure and feeling of an ancient folk tale. It concerns an orphan who must make her way through a haunted, threatening landscape protected only by her own good sense and a powerful, not entirely trustworthy companion.” In his 1976 book The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales, Bruno Bettelheim argued that stories such as those collected by the Brothers Grimm allow children symbolically to grapple with the heart of darkness so as to prepare for life in a menacing world. Pawlikowski’s laconic tale explores the quest for identity as it takes up the question of the inevitability – even necessity – of wrongdoing. Ida suggests that the sins we commit to survive can be deserving of forgiveness.

For such a short film (Ida clocks in at a mere 80 minutes), Pawlikowski’s spare script and Lukasz Zal and Ryszard Lenczewski’s sparse and beautifully composed black and white cinematography manage to juxtapose, with no overt display, the historic macrocosm of the tragic pall of the Holocaust – the end of which only exacted a furtive day to day life under the shadow of Polish communism – against the microcosm of the intersection of the two women’s lives.

New York Times film critic A. O. Scott astutely observes that “Ida has some of the structure and feeling of an ancient folk tale. It concerns an orphan who must make her way through a haunted, threatening landscape protected only by her own good sense and a powerful, not entirely trustworthy companion.” In his 1976 book The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales, Bruno Bettelheim argued that stories such as those collected by the Brothers Grimm allow children symbolically to grapple with the heart of darkness so as to prepare for life in a menacing world. Pawlikowski’s laconic tale explores the quest for identity as it takes up the question of the inevitability – even necessity – of wrongdoing. Ida suggests that the sins we commit to survive can be deserving of forgiveness.